Traveling with a coyote: Brothers journey 4,000 miles to reunite with undocumented parents in US

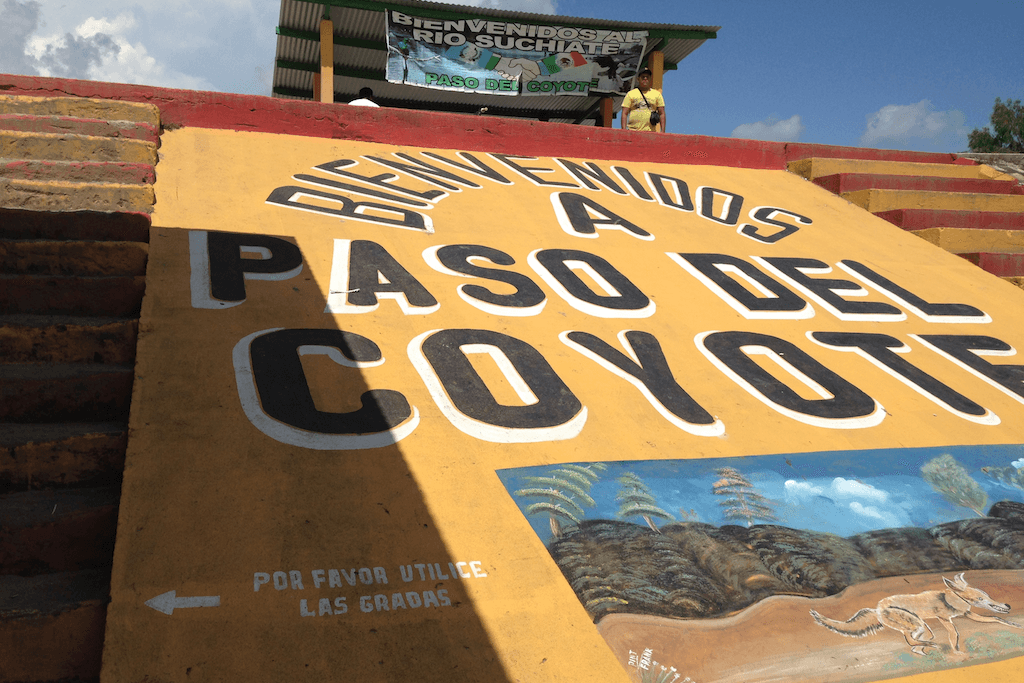

This location along the Suchiate River, on the border between Mexico and Guatemala, is known as ‘El Paso del Coyote’ or ‘Coyote’s Pass.’ This is where thousands of Central American migrants cross into Mexico each year with the help of human smugglers.

MEXICO CITY – Only the most desperate parents put their children in the hands of a human smuggler for a journey to the United States that can put them face-to-face with kidnappers and end in arrest, detainment or worse.

But an undocumented couple living in Baltimore, Maryland worried even more about the possibility that their two boys would grow up like orphans on the outskirts of homicide-riddled Sonsonate, El Salvador. So Jose, 35, and Ester, 33, themselves undocumented Salvadoran immigrants, began a quest to reunite their family illegally in the US.

In so doing, their children became some of the nearly 58,000 unaccompanied child immigrants who have crossed the southern US border since October last year. It’s a journey that entailed sometimes unspeakable danger for the boys and heart-wrenching uncertainty for their parents. The trip spans four countries, dozens of police checkpoints, cities soaked with the bloodshed of narcotrafficking turf wars, and approximately 4,000 miles — three times the distance between New York and Miami.

In 2005, Jose and Ester were living outside Sonsonate and their second son had just been born. Jose said he took one look at the infant and thought: “What I earn here will never be enough to live on.”

Three months later, Jose packed a bag for the US and left his family behind. In Mexico, he was abandoned by the coyotes guiding him and fell into the hands of immigration officials. A few days after he was deported to El Salvador, he tried again. That time he made it across the US border, making his way up to Virginia and Washington, DC and working odd jobs. Eventually, he landed a position at a cleaning company in Baltimore and started thinking about bringing his wife north.

“There are many broken homes [in El Salvador] because someone works here [in the US],” Jose said in his two-bedroom apartment in Maryland. “Many guys have other partners here and have separate families. And they forget about the family they left in their country… We didn’t want it to be like that.”

So in 2012, he paid a smuggler — also known as a coyote — more than $7,000 for Ester’s passage. Their boys, Kevin and Jose Jr., then ages 10 and 7, were left in the care of their aunt, who Jose and Ester thought would provide a safe home for the boys.

Ester’s trip was full of peril. She, like Jose, was caught and deported from Mexico. And just over the US border, her coyotes turned on her, holding Ester hostage for ransom. Jose had to borrow $1,000 from a friend to secure his wife’s release.

Trouble at Home

Meanwhile, back in El Salvador, things became increasingly dangerous for the boys. Gangs moved into the neighborhood. Stray bullets were hitting neighbors. Sonsonate has one of the highest homicide rates in El Salvador, which itself has the fourth-highest murder rate in the world. Jose and Ester had to be cautious about the kinds of gifts they sent home to their children.

"You have to be especially careful when you buy shoes there,” Jose said, noting a particular brand of sneakers, Nike Cortez, can cause a child to become the target of gangs. "You can’t buy just any shoes because you can lose your life for [wearing] them."

Within a year after their mother’s departure, violence was invading the boys’ lives as well. The aunt and other relatives beat Kevin and Jose Jr. with belts and yelled insults at them. Eventually the aunt abandoned them.

"We are to blame for having left them alone and not thought that they would suffer so many things with other people,” Ester said, in a voice quivering with worry and fear.

A 22-year-old cousin with two of her own children took over the boys’ care. But Jose and Ester felt she was too young to take care of so many kids. They said their only option was to bring the boys out of El Salvador.

Danger within the home in places like Sonsonate can be grounds for protective visas or humanitarian asylum in the US, said Michelle Mendez, senior managing attorney for Catholic Charities, a nonprofit organization that has been providing legal support for many of the children in this recent surge of immigrants to the US.

"This is definitely, in our estimation, a child refugee issue,” Mendez said, referring to the recent wave of unaccompanied minors, the majority of whom start in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

A recent survey by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees found that 58 percent of the children in the recent surge are fleeing crime, threats or abuse and could be eligible for protection in the United States.

But Jose worried about the risks and time involved in going back to El Salvador to apply for asylum.

If he sent Ester back, he feared their marriage could disintegrate.

And if they both returned, leaving behind their jobs and an apartment in Maryland, they might never be able to return to the US, and once again struggle in El Salvador.

So Jose and Ester started putting in 12-hour days at the cleaning company, scrubbing, vacuuming and hauling trash bags at apartment buildings to save up for the hefty fee required to pay a coyote to take Kevin and Jose Jr. into the US: $10,000.

They also negotiated a specific route for the journey. For one thing, they would not permit their children to board the so-called Death Train, also know as The Beast, which crosses Mexico and is known as an easy target for drug cartels.

Instead the boys would travel by car and bus, with the fee including three attempts to cross the US border.

The first try was in May. But a few days into the journey, the boys were caught by police in Mexico and sent to an immigrant detention center, guarded by police and barbed wire. After 20 days in detention they were deported, two of 12,400 children sent away from Mexico this year. They were flown to El Salvador, where an uncle picked them up.

For Kevin, the flight was an adventure “in the clouds.” But his delight was short-lived. By June the boys were back in Ester and Jose’s house with their cousin. The place had fallen into disrepair. Mangoes rotted on a tree in the backyard. The boys played soccer in the living room because gangs occupied the streets.

Every day, Kevin kept in touch with his parents using Facebook. Scratchy telephone lines and unstable video chats are the only ways 8-year-old Jose Jr. has ever known his father; he was just three months old when his dad left for the United States. “The first time [we] bought a computer, that’s when I saw him,” the boy recalled. He said his dad looked chubby—“just like me.”

The second trip north was in mid-June. The group made it through Guatemala and as far as the southern Mexican city of Tapachula. Shortly after they checked into a hotel, men in police uniforms burst into the room the boys shared with others in their group of prospective immigrants and demanded money. Another family traveling with the boys managed to relay the message to Jose that they were being kidnapped. Frantic, Jose tried to reach the coyote, but the number was suddenly “non-working.”

Then, for two long days, Jose and Ester waited.

Finally, the coyote called. He said he had paid a thousand dollars’ ransom for each boy, and that they were free.

A few days later the coyote called again. They were on the Mexican side of the border, just south of McAllen, Texas, and would try to cross that night.

Then, another three days of silence.

"I was calling around to a bunch of organizations to see if they could find the boys or find out what happened,” Jose said. He tried to keep his mind away from the stories of immigrants dying in the desert or washing up on the banks of the Rio Grande.

Jose got a call from US immigration officials in early July. The boys had left their hotel to cross the Rio Grande with one of the coyote’s assistants. Now the boys were in detention, but this time in the US. They children were kept in an overcrowded center, slept on cots in rooms they described as freezing cold. Jose said the boys were transferred again and again – with no word on their whereabouts. After a week, he tracked them down to a children’s shelter in Miami.

Unaccompanied children from Central America like Kevin and Jose Jr. are treated as possible trafficking victims under the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008. Immigration courts are severely backlogged so hearings can take weeks or months to happen.

While they wait, about 85 percent of the children are reunited with relatives in the United States, according to July testimony given by Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Mathews Burwell. Most of the remaining 15 percent are placed in foster care settings or other home-based care. Some children remain in shelters, which are often very crowded.

“The influx of unaccompanied children across our nation's borders is an urgent humanitarian situation that calls for a robust humanitarian response,” she said at the hearing before the Senate Appropriations Committee.

President Obama asked Congress for $3.7 billion to address the influx of child migrants, beef up border enforcement, hire more immigration judges and provide more space for the children as they await immigration hearings.

While there are reports that immigration courts have sped up the hearings for some unaccompanied children in the latest wave, Jose said his boys were released without a court date.

Moment of Truth

The family reunited last month at the Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport. There were no toys or balloons. The truth is, Jose couldn’t believe the social workers would really come through.

"I was really anxious. Would they come? Would there be bad news? Would they not be able to make it?" he said.

Jose and Ester waited for 40 minutes at the arrivals area. At 3 p.m., Kevin and Jose Jr. walked around the corner. Years had passed since they’d seen each other in person. The boy were 11 and 8 years old when they walked off the plane in July.

There was joy, Jose said, "but also a little bit of pain for all that they had gone through and suffered to be with us.”

Now that the family is back together in Maryland, Jose has been working to make sure they stay together. That means hiring a lawyer and going to court for the boys. Because Jose and Ester don't have papers either, the legal process that decides the fate of their children could shine a light on them as well.

Ahilan Arulanantham of the American Civil Liberties Union said whether migrant children are allowed to stay in the US seems to rest on the chance that the children are able to find a lawyer.

“There are remarkable set of pro bono legal resources… working in this field,” Arulanantham said. “But unfortunately the need has completely overwhelmed those private charitable legal resources.”

Before the crisis, only about half of the children faced immigration court without an attorney, he said.

“And that number no doubt has increased since the number of children coming has increased,” he said.

With an attorney, roughly half of migrant children are allowed to stay in the United States, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, a project at Syracuse University that tracks immigration court statistics. Without an attorney, the odds fall to one in ten.

For now, Jose and his family are enjoying the time they have together – eating traditional Salvadoran pupusas, celebrating Jose Jr.’s ninth birthday and getting ready for the newest member of the family: Ester is seven months’ pregnant.

"We’ve fought so hard to be together, and I hope to God that everything works out and we can stay together,” Jose said. "No one takes better care of kids than their parents."

This story was produced by Round Earth Media, a nonprofit organization that mentors the next generation of international journalists. Julia Botero, Eric Lemus and Manuel Ureste contributed to the reporting, produced in partnership with PRI's The World.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!