Obama visits Israel; Middle East scholar Rashid Khalidi weighs in

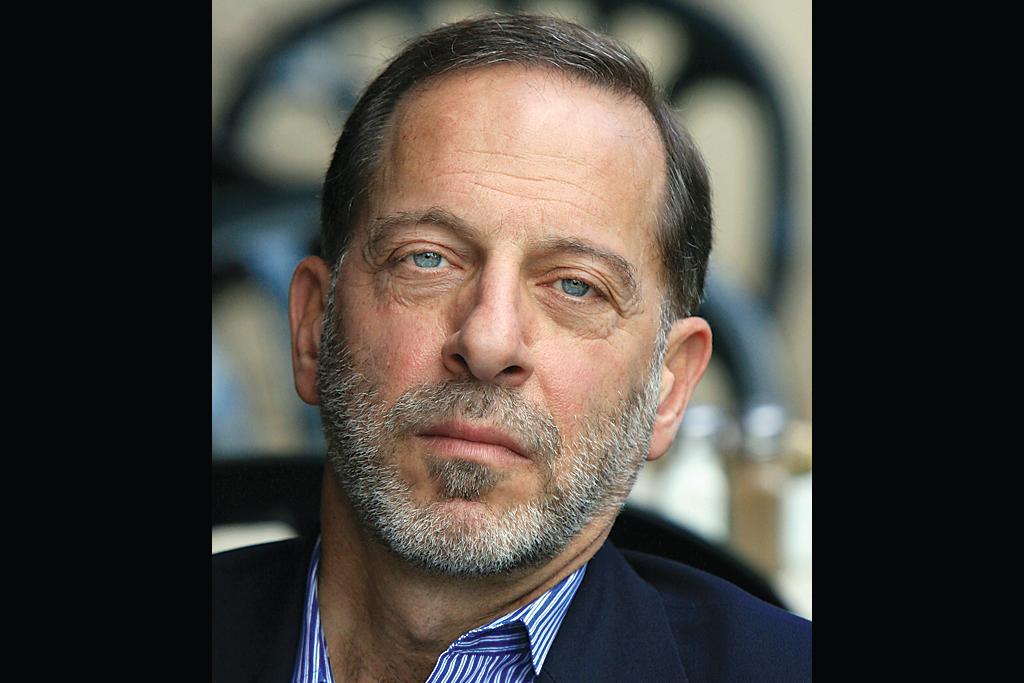

Middle East scholar Rashid Khalidi.

On Wednesday, US President Barack Obama begins his first official trip to Israel as president.

GlobalPost talked with Middle East scholar Rashid Khalidi, author of Brokers of Deceit and Edward Said Professor of Modern Arab Studies at Columbia University about the current landscape in Israel and the Palestinian Territories.

What do you hope will emerge from President Obama’s upcoming visit to Israel?

I actually don’t have very high expectations for this visit. It’s very clear that this Israeli government is going to be even less forthcoming on the issues of settlements, occupation, and the resolution of the conflict with the Palestinians.

It’s not quite clear precisely what, if anything, the president intended to achieve with this trip. It may just be that this was the obligatory trip for an American president to make during his second term.

The White House has said that the president is not going with any peace process in hand, but what do you think a just solution to the Israel-Palestinian conflict would look like? In your book you talk about the term “peace process” being a false term, could you talk a bit about that?

In the decades since the Madrid Peace Conference in 1991, and in the years leading up to and after the Oslo Accords – which are the basis of the Palestinian Authority and the arrangements that exist – the situation has gone from bad to much, much worse.

The number of settlers in occupied territory has nearly tripled, and the restriction on Palestinian movements has become intolerably constrictive – Palestinians can’t move anywhere. Jerusalem has since been closed off to them. Palestinians can’t move from the West Bank to Gaza, they cannot enter Israel.

All of this has happened on the watch of several American presidents, and under the rubric of a peace process. What I argue is that we certainly have a process, but it has not only not produced peace, but it has made peace measurably harder to achieve.

As far as what a just solution would involve, it depends on what questions you ask. If you start off by saying the problem is Israel’s security, or the problem is you have two equal parties and both have to compromise – if you start from the wrong premise, then you’re not going to get a solution to the problem because those are the wrong premises.

These are not equal parties – there’s one party half of whose people where expelled from their homes in 1948. The other half lived under occupation since 1967. If you see the problem that way, then a just resolution to the problem involves ending occupation and involves ending settlement and involves giving rights to Palestinians that are equal to the rights that Israelis have. However that’s done – that’s a matter for negotiation.

In your talk at Cambridge Forum recently, I think someone in the audience asked a question about settlements and the feasibility of dismantling them. Just now you said ending settlements would have to be part of a just solution. How realistic is that outcome?

If the end solution is going to be a one-state solution where all citizens would have equal rights, and Palestinians would vote in Palestinian elections and Israelis in the Israeli elections, and somehow you would have a one-state setup – a federation or something like that – then the issue of the settlements recedes, and the question becomes about Palestinians getting equal rights inside Israel.

If you’re talking about a two-state solution, the Palestinians were granted a little under 45 percent of the territory in Palestine by the partition resolution of 1947. After the dust had settled in 1949, Israel controlled well over 70 percent of the territory. And if what remains is the 22-odd percent, which is the West Bank and Gaza – which Israel is now proposing to take large chunks of for these so-called settlement blocks, and the annexation of East Jerusalem and so on and so forth – well, that’s not a two-state solution.

That’s Israel and a little Palestine postage stamp attached to it, especially if you keep the settlement blocks where they are because the so-called settlement blocks are in fact established, by and large, in ways that were designed to cut the West Bank into ribbons, such that a contiguous, viable state was an impossibility.

I see the unfeasibility of it. Menachem Begin, Yitzhak Shamir and Israeli prime ministers after him, and the planners that worked for them – notably later Prime Minister Ariel Sharon in his capacity as agriculture minister – did everything possible to make it unfeasible to separate Israel from the occupied territories, and to make the Palestinian state impossible.

If they succeeded then we have to go to plan B, which is figuring out how you deal with this unified country under one sovereignty and how you achieve equal rights for both Jews and Arabs in that single sovereign state.

In light of the current state of things, what is your opinion of Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas?

I think that the entire generation of leadership on both sides that have brought the Palestinians to their current state of weakness and division — a state of paralysis unparalleled since the 1950s — have comprehensively failed their people. The most honorable thing for them to do would be to give way to a younger generation and to different ideas.

I think that the idea of negotiating from a position of weakness, and accepting — and in fact operating in support of — Israeli occupation, which in large measure I think the Palestinian Authority's security forces do in the West Bank, is an unworthy objective for people who are trying to achieve self-determination for their people.

I think that the means adopted by Hamas, which have brought great suffering on the Palestinians in the Gaza Strip, and haven’t succeeded in achieving very much at all, are also very futile.

Both wings of the Palestinian political leadership have comprehensively failed, and the most honorable thing for them to do would be to give way to others with better ideas.

Would you consider Hamas a terrorist organization? The US has designated them as such.

American designation of terrorist organizations partakes of something I talk about in my book. If attacks on civilians are the definition of terrorism, and under various aspects of international law that’s a reasonable yardstick, then I think you have to judge both sides by the same yardstick.

The number of Palestinian civilians who have been slaughtered by Israel is considerably larger* than the number of Israeli civilians who have been murdered by Palestinian rockets or other forms of violence. And so if this lot is “terrorist” insofar as they attack civilians, then certainly the other lot also is. [* – Figures provided by B’Tselem, the Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories, established in February 1989 by a group of prominent academics, attorneys, journalists, and Israeli parliament members.]

A lot of what Hezbollah or even Hamas does, which is directed at military occupation, can’t legitimately be called terrorism. I think attacks on civilians can, absolutely.

You did mention that using violence as a solution to bring about change is not the right approach.

In the Palestine case, yes.

The recent talk of a unity government between Hamas and Fatah — do you think it would be possible to move forward with something like that without legitimizing the violence that Hamas uses?

I don’t know — that’s my personal view. I think that against this enemy, in this context, the use of violence is self-defeating. I think the use of violence against civilians is never justified. It’s immoral; it’s against international law.

But I’m talking about the use of violence which is legitimate under international law such as the kind aimed against military occupation forces. The fact that Israel has successfully posed as the victim even though it is the victimizer in this conflict makes it very, very difficult to use violence without reinforcing some of the worst tendencies of Israeli society, and some kinds of support for Israel that ultimately outweigh any benefit you’d get from legitimate use of violence against say, Israeli military occupational forces. So I would argue that for several reasons, it's unwise.

I think if you look at this piece in the New York Times Sunday Magazine this weekend you’ll see that that same conclusion has been reached by villagers up and down the West Bank: that the use of violence is futile. The proper means to resist is non-violent.

Going back to President Obama, what was your opinion of his speech in Cairo four years ago, and have your feelings changed since then?

In my book I actually analyze that speech, because I don’t think a lot of people did. It was infinitely more devoted to telling its Arab and Middle Eastern audience about sufferings of the Jewish people than it was to expressing sympathy for Middle Eastern grievances or for the Palestinian side. It’s worth going back and reading that speech. Much more is devoted to laying out the evils of the Holocaust, an Israeli view, and Israeli suffering than to a Palestinian perspective.

I think that anybody who goes back and actually reads that speech — who doesn’t believe the hype about it, doesn’t reflect the shock of the Israelis that the president could have come to Cairo and not gone on to Israel — doesn’t respond to those cues but actually reads the speech, will see that it’s a speech that includes some really boiler plate stuff presenting an Israeli point of view.

I think it wasn’t quite the breakthrough some people thought it might be.

How would you explain how it was received in the Middle East at the time? At the time it was greeted with –

Rapture! People read into Barack Obama’s election all over the world — in the United States, in the Middle East, everywhere — change.

Which in some respects is justified. I mean, an African-American being elected president of the United States, a person who’s lived outside the United States for significant parts of his life being elected president, someone whose father is of Muslim heritage being elected president, these were all quite striking facts. Being elected, as President Obama was in 2008, with electoral votes from two of the confederate states, Virginia and North Carolina, this is historic stuff.

But to leap from that to thinking that he was what everybody read into him, I mean everybody read into him what they thought they wanted in the world — but he wasn’t those things. He is not someone who’s willing to take enormous risks.

He’s a pragmatist, he’s careful, he’s compromising — the things we’ve come to know about him. Anyone who’s followed his career would have been able to tell, would have been able to say.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!