Mock stars: Myanmar’s pop plagiarists

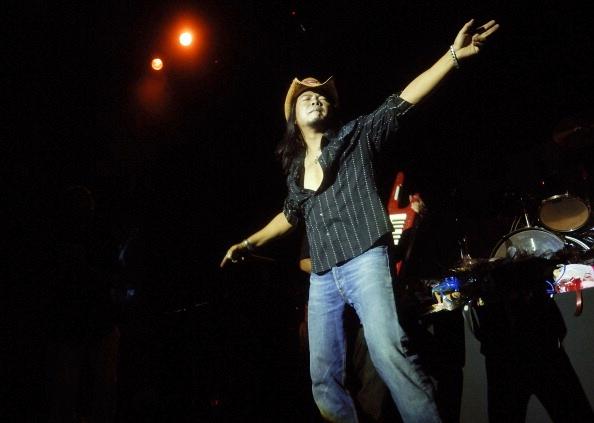

Zaw Win Htut, aka the “Emperor” is among Myanmar’s most popular rock stars. Like many, he became famous by singing plagiarized Western hits with Burmese lyrics — known as copy tracks. He has since recorded original music, and is often quoted as saying that playing copy tracks is like wearing someone else’s shirt.

YANGON, Myanmar — Imagine a game of “Name That Tune” with two metal heads as contestants.

One is from Myanmar, a Southeast Asian nation still shaking off totalitarian rule.

The other is from Florida.

Within six notes — and even after six beers — both could identify the iconic guitar intro to “Enter Sandman” by Metallica. It is, after all, the best-known riff by one of the most popular metal bands ever. But in Myanmar, the isolated nation formerly titled Burma, the song is known by an entirely different name: “Exits”by the square-jawed, tatted-up rocker Lay Phyu.

Who the hell is Lay Phyu, the Floridian head-banger might ask? Inside Myanmar, he’s the biggest rock star alive.

And like most musical acts in Myanmar, he rose to stardom by ripping off foreign hits note for note, subbing in Burmese lyrics and vocals and passing them off as wholly original to unsuspecting fans.

Many of whom might ask, “Who the hell is Metallica?”

In Myanmar, plagiarism isn’t a sporadic indulgence among top performers. It is the engine that drives the nation’s pop music industry. Turning on the radio is like wading into an alternate universe where Motley Crue, Coldplay and Lady Gaga have been abducted and forced to sing in Burmese, Myanmar’s national language. The phenomenon is so rampant that it has a name: “copy track.” (A song that’s actually original? That’s called “own tune.”)

“Of course, it’s stealing. But the general public has no idea,” said Diramore, a 39-year-old pop singer, composer and associate professor at Myanmar’s National University of Arts and Culture.

“They’ve never heard the song. So, to them, it’s a hit.”

Professional Plagiarists

Like many of Myanmar’s anomalies, copy tracks can be blamed on the domineering junta that has only recently relinquished direct control. Over the last five decades, when the military wasn’t crushing dissidents or squandering the nation’s wealth, it was struggling to quarantine the nation’s culture against outside influence. Until last year, all media circulated in Myanmar required approval from censorship panels eliminating content deemed revolutionary, salacious or even overtly foreign.

Under draconian cultural censorship, Western music was until recently only available via CDs or tapes smuggled in from abroad.

So just what happens when you isolate 60 million people and filter all of their entertainment through stuffy censors — all in a sonic landscape unfettered by copyright laws?

You spawn a musical platypus, the “copy track,” a genre that defies easy description. It is not a tribute or cover song; the original composer is rarely acknowledged. It is not a wholesale theft; the lyrics, at least, are original and occasionally quite poetic.

Like 1960s singer Pat Boone, who churned out milquetoast covers of soul records for white America, the copy track industry revamps foreign hits with vanilla-sweet, censor-friendly Burmese lyrics.

The copy track genre is deeply endemic to Myanmar’s music scene. For the first concert by an international artist in decades — an MTV-backed, US embassy-endorsed performance by Jason Mraz in December — the promoters assembled the Myanmar’s biggest stars: Phyu Phyu Kyaw Thein, R Zarni and Sai Sai.

Vocal talent aside, all could be fairly describe as professional plagiarists. Between the three, their careers rest on hits pilfered from Celine Dion, Bob Marley, Nickelback and Evanescence to name only a few. (Rapper Sai Sai is also Coca-Cola’s “brand ambassador” in Myanmar.)

Myanmar is currently experiencing joyous upheaval: The junta is defunct, a quasi-democratic parliament is in power, pre-censorship has ended, investors arrive in droves and the internet is largely free of restrictions. Described as an “outpost of tyranny” by the US State Department in 2005, it is now hailed by Barack Obama as a nation ready to “set a great example to the world.”

Yet artists like Diramore fear that, as outsiders peer into Myanmar, copy tracks will project an image of creative bankruptcy. “These copiers don’t need to know about arrangement or music theory. They just steal,” Diramore said. “I never have and never will do a copy track. My conscience is clean.”

Trapped in Myanmar

Wunna Kyaw’s conscience is not so clean.

The 35-year-old Yangon commercial producer has a confession: Two years ago, he ripped off an ABBA song and used it as the sound track to a breast enlargement cream ad.

The song was “Chiquitita,” a mournful ode to a lovesick girl. “Chiquitita, tell me what’s wrong,” croons the Swedish soft-pop quartet. “You’re enchained by your own sorrow / In your eyes, there is no hope for tomorrow.”

By the time Wunna Kyaw reformatted the tune, the TV spot was a tender ode to boob lotion. “It went something like, ‘Life is full of happiness. The next most important thing, for girls, is beauty. This breast enlargement cream will enhance your beauty.’”

“I felt ashamed,” Wunna Kyaw said.

His client, however, was thrilled after the mélange of saccharine Scandinavian pop, attractive models and breast enhancement hopes hit TV screnes.

Myanmar’s pop idols aren’t the only ones using foreign hits to cash in. Copy tracks have become the soundtrack to advertising jingles for ruby-and-jade jewelers, construction empires, instant coffee powder and budget cosmetics. In Myanmar, the driving melody to “You Give Love a Bad Name” is a gold shop theme, not a Bon Jovi riff; N Sync’s “Bye Bye Bye” is repurposed to advertise baby shoes.

These ads run incessantly on TV stations owned by the government and the military. Copy track ads are so pervasive, Wunna Kyaw said, that corporations often approach ad makers with a Western pop single already selected. “Locals become familiar with these songs. They remember the melodies,” he said. “We have a rule: if a three-year-old kid can sing along to your commercial … you’ll make a big profit.”

For now, the only deterrent to plagiarizing pop for profit are high-minded ideals and a flimsy piece of legislation — the “Burma Copyright Act of 1911” — which dates back to the Myanmar’s years under British colonial occupation. These codes on “cinematographs” and “engravings” pre-date television, let alone MP3s and DVDs. “We just don’t have proper (intellectual property) laws in this country,” Wunna Kyaw said.

But Myanmar’s creative industry shouldn’t quit plagiarizing because of some state decree, Wunna Kyaw said. His own production firm, Miracle Post, has sworn off copy tracks for dignity’s sake.

He has encouraged upstart filmmakers to see that intellectual property theft negates their potential to grow beyond Myanmar. He cites a Yangon-based movie crew scrambling to clear rights for a plagiarized Japanese song after their film’s acceptance into an international festival in Singapore.

Those who don’t repent, Wunna Kyaw said, will be “trapped in Myanmar … because they’ll get sued if they ever leave.”

Poison in your dreams

At a glance — through Western eyes at least — copy tracks are derivative, cheesy and perhaps even criminal. But does all that condescension cloud glimmers of real talent?

In a recent academic study of Myanmar’s copy track phenomenon, Burmese-speaking University of Sydney anthropologist Jane M. Ferguson describes copy tracks as an art form that “breaks from, resists and receives international pop all at once.”

Without copy tracks, she writes, a population living under asphyxiating censorship would have had no access to rock ‘n’ roll. She also warns critics who “look down their noses” at the copy tracks: “The pitfall to this stance is that it ignores the skill of musicians who interpret songs.”

Consider the role of copy tracks in the rise of Acid, the Yangon rap group credited with sparking off Myanmar’s raging hip-hop craze. They began in the late 1990s, when censorship was in full swing, by studying rap CDs acquired through back channels. “I liked the music and I liked the style,” said Yan Yan Chan, 33, one of Acid’s founding members. “But I had no idea what they were saying.”

The lyrical thicket of slang and rapid-fire braggadocio was nearly impenetrable. “We figured out ‘Yo’ and ‘What’s up’ pretty easily,” he said. “Then we moved on to figuring out ‘bitch’ or ‘dope.’ We had dictionaries. But it was pretty obvious that ‘bitch’ didn’t refer to an actual female dog.”

Acid’s breakout single was “A Sate Ein Mat.” Translation: Poison in Your Dreams. “It was about partying, going all night without sleeping and turning the room upside down,” he said. The song’s beat — a hard drum loop pierced by intermittent squeals — would be instantly identifiable by almost any American who came of age in the 1990s.

It’s Cypress Hill’s “Insane in the Brain.”

“You have to understand,” Yan Yan Chan said. ““There was no one here to teach us how to do this. No one in the country knew how to produce a hip-hop beat.” Much of their first album, released in 2000, was sequenced by a heavy metal sound engineer because “he was the only guy using computers in a music studio,” Yan Yan Chan said.

The album barely survived intense scrutiny by government censors. “It came back with a big, red X,” he said. “They were like, ‘What the hell is this? A novel? Why so many lyrics?’”

Though Acid colored within lyrical lines drawn by censors, their music had its desired effect: pandemonium among parents across Myanmar. “If you listened to the album in your room,” Yan Yan Chan said, “your mom would bang on the door and ask, ‘Are people fighting in there!?’ If you played it in the main room, your whole family would run away.”

It’s hard to tell if even Cypress Hill would deride Acid as plagiarists. The group’s origin tale is filled with enough rebellion, hustle and ingenuity to offset petty concerns over stolen beats. Besides, hip-hop is a borrow-and-swap culture built on sampled bass riffs and looped soul samples. And in a new-generation context — marked by file sharing and mash-ups — copy tracks look more forgivable.

Yan Yan Chan has since gravitated away from copy tracks. “The mentality has changed,” he said. “We’re starting to believe we can do everything ourselves.” Still, he chafes at the implication that his childhood heroes — such as rocker Lay Phyu — have anything to apologize for.

Sure, he’s ripped off dozens of American rock songs. But just as Acid brought hip-hop to Myanmar’s crumbling streets, Lay Phyu brought heavy metal to this cloistered and oppressed nation of millions. So who the hell is Metallica?

“Growing up, all my favorite songs were copy tracks. I had no idea,” Yan Yan Chan said. “Now I do. But I still love them just the same.”