Integrity of the 2015 Nigerian elections is paramount to the future of Africa

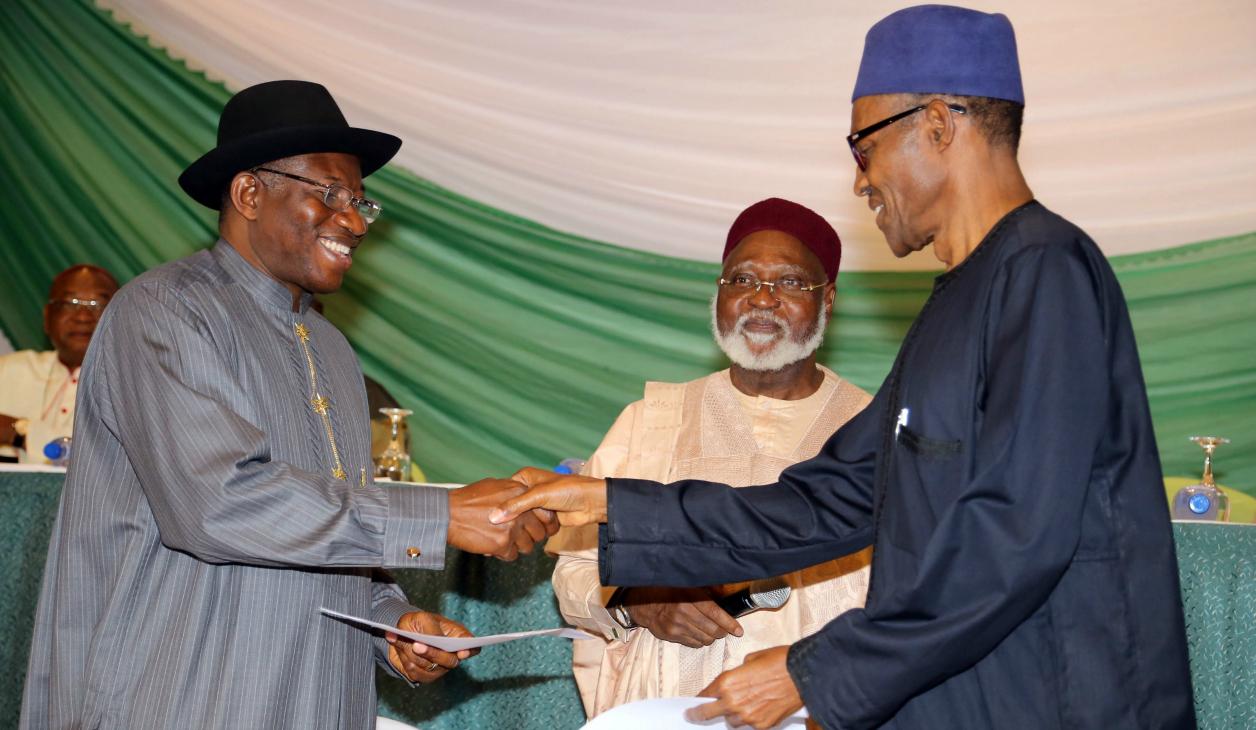

Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan (L) and APC main opposition party's presidential candidate Mohammadu Buhari shake hands after signing the renewal of the pledge for peaceful elections in Abuja.

By John Rosenburg

WASHINGTON — It has been said that, “As goes Nigeria, so goes the rest of Africa.” The importance of Nigeria’s role in the economic and political machinery of Africa is without question. The real question is what will happen to Africa as a whole if Nigeria descends into chaos and violence after the tightly contested presidential election on March 28.

The Abuja Accord, signed by President Goodluck Jonathan, Muhammadu Buhari and 10 other presidential candidates this past January, was a significant step in preventing this kind of negative outcome.

The accord spells out the responsibilities of all candidates, including their political parties, to refrain from the incitement of violence before, during and after the elections and to police the actions of their own membership who might promote civil unrest. Additionally, it commits all parties to an impartially fair, free and open election.

There is concern that voters will not be able to make it to the polls, given security concerns in the northeast of Nigeria brought on by the Boko Haram terrorist group and in the Niger Delta region where several armed groups regularly carry out sabotage, kidnapping and attacks.

President Goodluck Jonathan’s administration had already taken steps in meeting the Abuja Accord goals even before it had been formally signed. Working with the Independent National Election Commission (INEC), Jonathan has been striving to prevent voter and ballot fraud through the utilization of biometric permanent voter cards (PVCs), which are issued to eligible voters for use at nearly 120,000 polling locations throughout the country.

While some international observers contend there was no reason in setting back the election from February 14 to March 28, Jonathan and INEC cited the threat of violence by Boko Haram in Borno, Yobe and Adamawa states that could have the net effect of preventing more than four million people from voting.

To remedy this situation, the Nigerian military is working with Chad, Cameroon and Niger in a campaign to root out Boko Haram, reclaiming territory under its control and securing the safety of the people living there.

This action has enabled the distribution of millions of additional PVCs and card readers so that more voters can cast their votes.

Buhari, Jonathan’s chief opponent, threatened in late February to pull out of the accord. A retired general and former president of Nigeria by way of a coup in the 1980s, Buhari claimed that Jonathan’s campaign had been pointing out elements of his public service record that did not cast him in the best light. After realizing the negative effect on his image, Buhari later reaffirmed his commitment to the accord.

In the Transformation Agenda, Jonathan has laid out his plans to move the country’s policies away from “business as usual” in everything from education, to health services, to judicial reform and job creation. It shows tremendous promise, but it will only work if there remains a steady hand to guide it.

Given Nigeria’s pre-eminent role on the continent, a fair and free election is crucial to the future of Africa as a whole. The Nigerian giant is beginning to stand up after years of lying flat on the ground because of economic and political malaise. It would be a tragedy of epic proportions if the nation were to trip and fall back to earth because of violence, turmoil and an election that is less than credible.

John M. Rosenberg is a former foreign reporter and current Africa and international affairs author living in Washington, DC. His work regularly appears in the Philadelphia Inquirer and numerous other international news outlets.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!