How Islam became a justification for militant violence

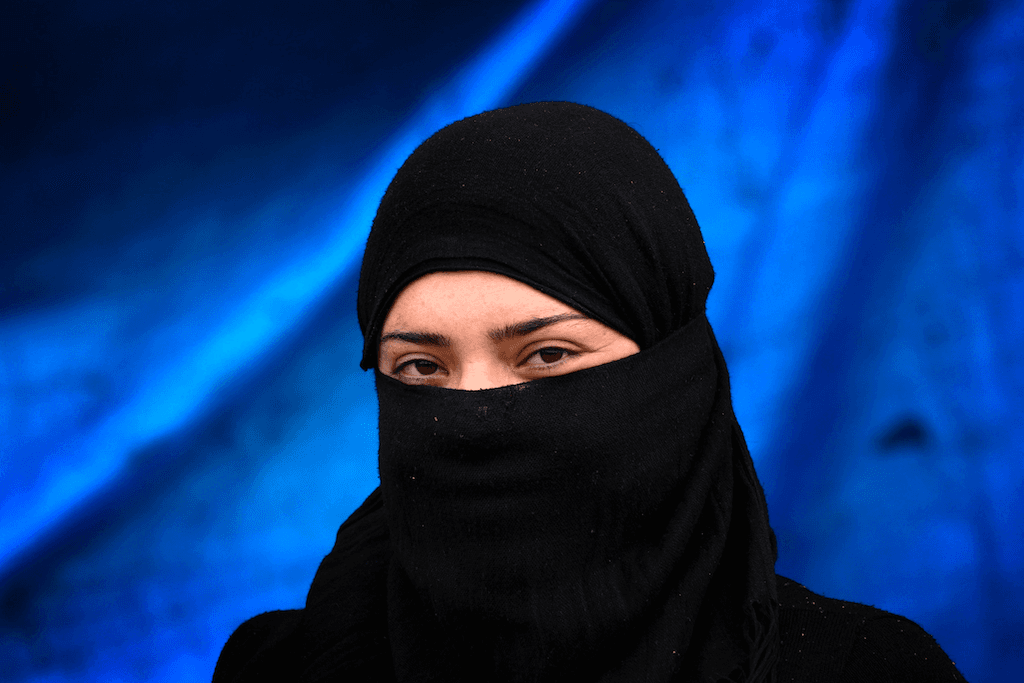

A displaced Iraqi woman from the Yazidi community, who fled violence between Islamic State (IS) group jihadists and Peshmerga fighters in the northern Iraqi town of Sinjar, looks on at Dawodiya camp for internally displaced people in the Kurdish city of Dohuk, in Iraq’s northern autonomous Kurdistan region, on January 14, 2015.

The past year has been a particularly cruel one for minorities in the Middle East.

After Islamic State (IS) militants seized Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city, last June, they gave Christian residents an ultimatum: convert to Islam, pay a religious tax, or be driven out of their homes. Many Christians fled to Turkey or the Kurdish autonomous region in northern Iraq. The extremists drove out a Christian population that had lived in Mosul for two millennia.

In early August, IS fighters mounted an offensive toward the Kurdish city of Erbil. The militants drove thousands of Iraqi Christians and Yazidis out of their homes in northern Iraq, forcing them to take refuge on a barren mountain range called Mount Sinjar. As IS militants besieged the mountain, the world grew alarmed that the Yazidis would be the victims of a religiously-motivated genocide.

President Barack Obama, who described the Yazidis as “a small and ancient religious sect,” vowed to avert a massacre. “They’re without food, they’re without water. People are starving. And children are dying of thirst,” Obama said in a speech explaining why he had authorized US airstrikes to break the siege.

Within weeks, the attack on Mount Sinjar was repelled and the media’s attention shifted elsewhere. But the Yazidis became another persecuted minority in the Middle East.

A similar strand of Islamic militancy inspired two jihadists to attack the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo on Jan. 7, killing 12 people. The rampage set off three days of bloodshed that left five more people dead. Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), which is based in Yemen, claimed responsibility for the attack and said it was intended to punish the publication for its frequent caricatures lampooning the Prophet Muhammad.

In late November, Pope Francis visited Turkey in his first trip as pontiff to a predominantly Muslim country. The pope and his counterpart in the Orthodox Church, Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, vowed to work together to prevent an exodus of Christians from the region.

“We cannot resign ourselves to a Middle East without Christians, who have professed the name of Jesus there for two thousand years,” the two leaders said in a common declaration. They encouraged “constructive dialogue with Islam based on mutual respect and friendship.”

When the US invaded Iraq in 2003, there were 1.5 million Christians living there. Today, the Christian population has dwindled to fewer than 400,000 — and many are on the run from the Islamic State.

The current status of religious minorities in the region is indeed dire, but it’s important to remember that there is a long history of tolerance within Islam for other religions. Islam coexisted with other faiths for over a millennium.

Over the past 50 years, militant movements and some Islamic regimes that favor a literalist approach to revealed texts have imposed austere interpretations of the Quran and of Islamic law, the Shariah, ones that run counter to a millennium of moderate understandings, including tolerance for other faiths. Shariah is not a monolithic system of medieval codes, set in stone and solely based on cruelty and punishment. Since the seventh century, the body of law has co-evolved with different strains of Islamic thought — tolerance versus intolerance, forgiveness versus punishment, innovative versus literalist.

To believers, Shariah is more than a collection of laws — it is infused with higher moral principles and ideals of justice. Shariah literally means “the path to the watering hole,” an important route in the desert societies of pre-Islamic Arabia.

Historically, Islamic law is based on four sources: the Quran, the sayings and traditions of the Prophet Muhammad (the Sunnah), analogical reasoning and the consensus of religious scholars. Because the Quran did not provide a system of laws, Islam’s early leaders would rely on the Sunnah, a collection of the prophet’s sayings and stories about his life. (The word Sunnah also means path, and it is the root of the designation “Sunni” — those who follow the prophet’s path — the dominant sect in Islam.)

In the 13th century, as the Mongols swept across Asia and sacked Baghdad, the Mongol warrior Hulegu (a grandson of Genghis Khan) asked Muslim jurists at the time: would they prefer to live under an unjust Muslim ruler or a just nonbeliever? Wanting to keep their heads, most preferred Hulegu’s rule. But one jurist forcefully rejected the Mongol invasion, and his decision reverberates to this day. Ibn Taymiyya, a scholar from Damascus, issued several fatwas — religious rulings — against the Mongols, who were threatening to overrun the Levant.

Ibn Taymiyya is the intellectual forefather to many modern-day Islamic militants who use his anti-Mongol fatwas — along with his rulings against Shia and other Muslim minorities — to justify violence against fellow Muslims, or to declare them infidels.

He also inspired the 18th century cleric Muhammad bin Abd al-Wahhab, the father of the Wahhabi strain of Islam that is dominant in Saudi Arabia today. Al-Wahhab decreed that many Muslims had abandoned the practices of their ancestors and his followers led a failed uprising against Ottoman rule in the Hijaz, the region of Arabia where Islam was founded.

The Wahhabi appropriation of Ibn Taymiyya’s teachings would have a profound impact on the future of Islamic militancy. The Wahhabis’ brief rule over Islam’s holy sites in the early 19th century introduced pilgrims from across the world to the idea that violent revolution could be construed as a religious obligation.

Today’s Islamic militants and repressive regimes — especially Saudi Arabia, which has used its oil wealth to export Wahhabi doctrine throughout the Muslim world — are obsessed with literalist interpretations of Shariah and punitive aspects of the Quran, as opposed to strands that emphasize Quranic exhortations to forgiveness. The weight of Islamic history skews toward moderate understandings, but in recent decades these regimes and militants have exerted great influence to breed intolerance.

How were so many minority communities able to coexist with Islam for over a millennium? For a long time, these groups reached an accommodation with Muslim rulers by emphasizing the notion that they were ahl al-kitab, or “people of the book.”

The Quran singled out Jews, Christians and Sabaeans (an ancient people who lived in what is now Yemen and southern Iraq) as possessors of books recognized by Islam as God’s revelation. As the Islamic empire expanded, Jews and Christians were granted a legal status in Muslim communities as protected subjects, known as dhimmis. They were allowed to practice their faith, govern their own communities and defend themselves from aggressors in exchange for paying a special tax, the jizyah.

Other groups — including the Samaritans, Yazidis and Zoroastrians — managed to secure this label as “people of the book” for themselves, and in doing so were able to coexist with the dominant religion. Islam was, especially in its initial centuries, a religion that could accommodate and incorporate ideas from elsewhere. It also did not seek to suppress the older faiths of the Middle East.

In his powerful short book, “In the Name of Identity: Violence and the Need to Belong,” the Lebanese novelist Amin Maalouf describes how in its early conquests, Islam had developed a “protocol of tolerance” and contrasts that with Christian societies at the time. Maalouf, himself a member of a religious minority as a Greek Catholic, wonders: “If my ancestors had been Muslims in a country conquered by Christian armies, instead of Christians in a country conquered by the forces of Islam, I don’t think they would have been allowed to live in their towns and villages, retaining their own religion, for over a thousand years.”

Maalouf notes that at the end of the 19th century, Istanbul, then the capital of the Ottoman Empire, had a majority of non-Muslims: Armenians, Greeks and Jews. “From the outset, and ever since, the history of Islam has reflected a remarkable ability to coexist with others,” he writes.

We must not allow that history to be overshadowed by overzealous regimes and the rise of the Islamic State, which views non-Muslims and even many Muslims as people to be forcibly converted, driven into exile or put to the sword. For a long time, there was another way.

Mohamad Bazzi is a journalism professor at New York University and a former Middle East bureau chief at Newsday. He is writing a book on the proxy wars between Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!