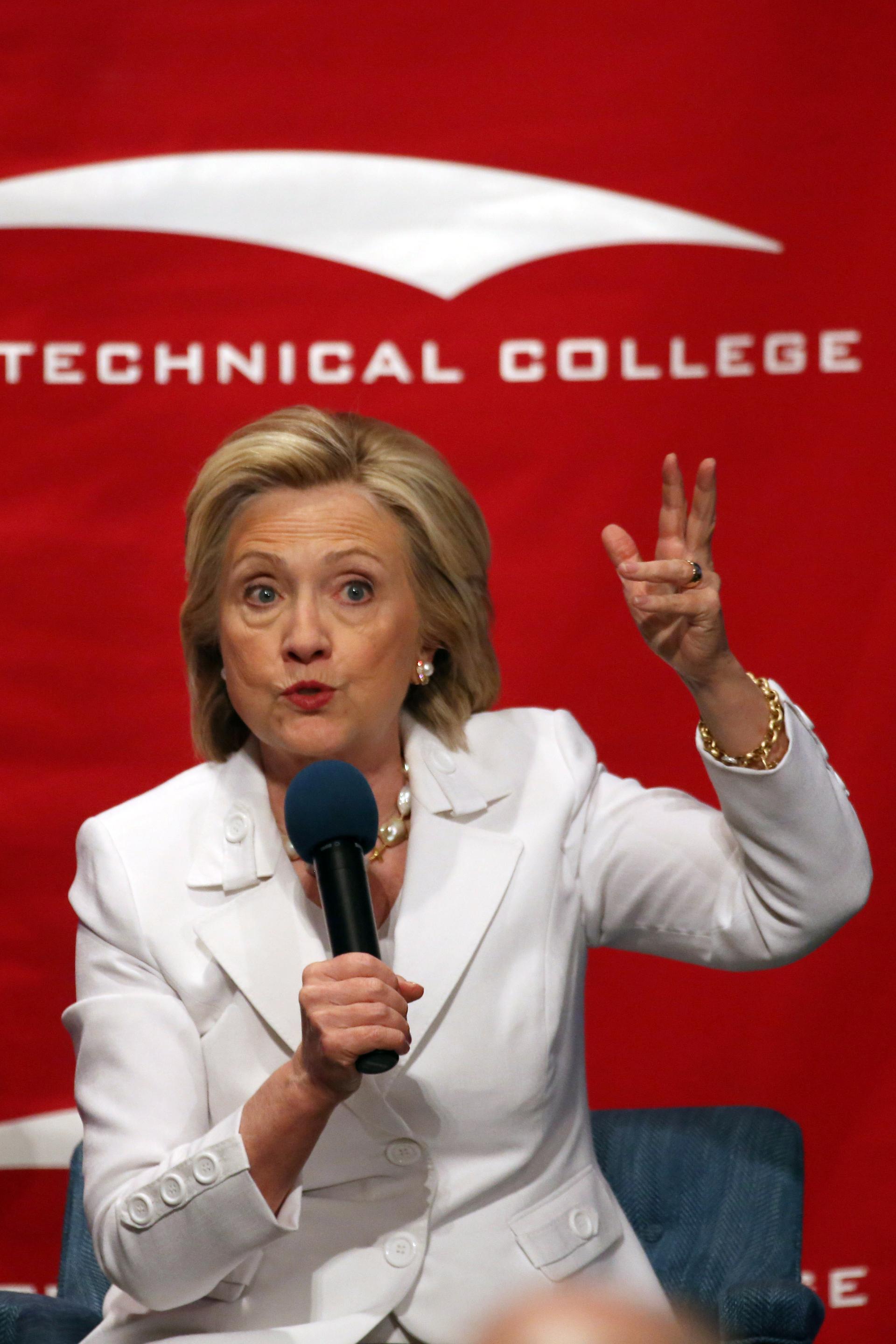

Hillary Clinton lauds apprenticeships as solution to youth unemployment

Presidential candidate Hillary Clinton wants to invest in the future of America’s youth by turning back to an old idea.

At a South Carolina technical high school last week, Clinton announced the first policy in her nascent campaign platform: $1,500 tax credits for businesses that host apprenticeships. These are typically programs in which students learn professional skills in the classroom while employers pay them to apply those skills on-site. But if recent trends are any indicator, young Americans are unlikely to get excited.

While apprenticeships are common in much of Europe, such programs have failed to make significant headway in the US. Over the last dozen years, the number of US apprenticeships has dropped 20 percent, to fewer than 400,000. Germany, which is considered the model country for apprenticeships, trains over two thirds of its working population in the programs each year. In the US, the number is below five percent.

In considering this disparity, Clinton told the audience, “We’ve done a disservice – a disservice to students, and to employers.”

The youth unemployment rate, around 13 percent, is nearly double the overall unemployment rate. Clinton said that apprenticeships are “one of those economic strategies that is a win-win-win,” and continued: “There is no reason for us to not get this done.”

But, as the low numbers of current apprenticeships indicate, this assertion is far from universally accepted.

“[Americans] still look at apprenticeships like a consolation pathway,” said Nicholas Wyman, CEO of the Institute for Workplace Skills and Innovation. This outlook stems from the fact that two-thirds of apprenticeships are in blue-collar, union-dominated industries like construction. According to US News and World Report, in 2013 construction workers earned a median annual income of just $35,000. The median annual income for 25 to 32-year-old college graduates was $45,000.

In Europe, a centuries-long legacy of apprenticeships and guilds, in which masters instructed trainees in apprenticeships, provided a basis for the growth of modern apprenticeships. But in the US, a trend towards valuing broad academic education, shying away from skills-based specialization and tracking, and skirting initiatives that bring government oversight into the private sector has stymied apprenticeships’ expansion.

Catalyzed in part by “A Nation at Risk,” the Reagan administration’s 1981 report on America’s public school system, an emphasis on ensuring that students graduate high school and continue to college became paramount.

Peter Vogel, writer and researcher on youth unemployment, said that this focus on higher education has limited the expansion of apprenticeships.

“You can do as much as you want from a policy perspective, but as long as parents say, ‘No, you go to college, you go to university, you get your degree,’” vocational training will not take hold, Vogel said. “Ultimately, [the success of apprenticeships] boils down to the necessity of making it attractive to pursue a different career path than getting a bachelor’s or a master’s degree.”

But Wyman, who completed a culinary apprenticeship in the late 1980s, described going on to attend college and then graduate school. He said that the idea that apprenticeships and higher education are mutually exclusive is a misconception.

“Apprentices can choose to go on to four-year college; there are all sorts of educational pathways,” Wyman said. “An apprenticeship certainly isn’t a dead-end street.”

Last summer, President Obama held a White House Summit on American Apprenticeship that aimed to validate this idea. Large employers, including Bank of America, Blue Cross/Blue Shield and IBM, as well as union representatives and small businesses owners attended the summit to advocate for the expansion of apprenticeships.

In large part, the businesses highlighted the need to hire employees that held skills that made them prepared for their jobs.

“Youth are not being adequately educated or trained for the jobs that are available,” said Dr. Nicole Goldin of NRG Advisory and the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Goldin said that apprentice programs help young people gain this “practical experience” that leads to long-term employment.

Soon after the summit, Obama pledged $100 million in grants that will increase the number of apprentices in “high-growth” occupations. He has also advocated for allocating $2 billion to initiatives that would double the number of US apprentices by 2020.

To date, though, apprenticeships have remained largely marginal. In 2008, businesses hired 83,000 new apprentices; by 2010, in the wake of the recession, they hired only two thirds of that number.

Robert Lerman, president of the Society of Government Economists, said that government support for apprentices has remained largely absent. “In some states, you have one person that is in charge of apprenticeships,” Lerman said. “We literally haven’t tried.”

Clinton’s proposal would aim to change this.

“It’s nothing groundbreaking, but it will go a long way to say to employers that the government wants to be part of the solution,” Wyman said.

Without apprenticeship programs, Lerman warned that a large sector of the economy will continue to lag. If public opinion could shift, and the policy focus around education could expand from college access to include alternative forms of education, apprenticeships could take hold, and provide an avenue to secure jobs for a generation of young people.

“When you have a robust apprenticeship system, young people get work experience,” Lerman said. “They build up a resume, so that even if the employer that supplies the apprenticeship doesn’t hire them, they have a record of employability.”

Without apprenticeship programs, he said, “We’re losing a lot of capacity, economic capacity, from a massive part of our population.”

The story you just read is accessible and free to all because thousands of listeners and readers contribute to our nonprofit newsroom. We go deep to bring you the human-centered international reporting that you know you can trust. To do this work and to do it well, we rely on the support of our listeners. If you appreciated our coverage this year, if there was a story that made you pause or a song that moved you, would you consider making a gift to sustain our work through 2024 and beyond?