China is increasingly arresting celebrities for drug use

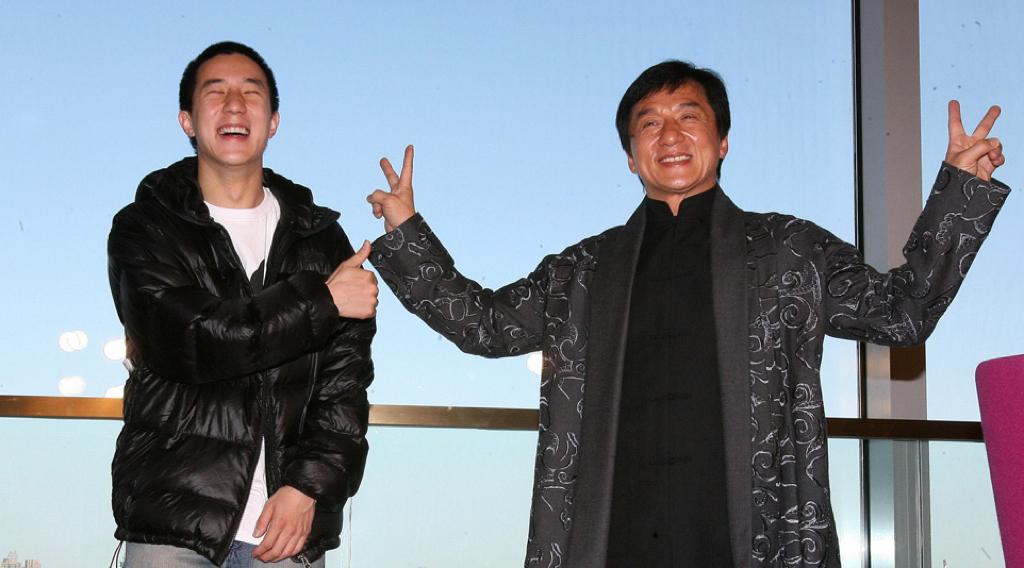

Hong Kong entertainer Jackie Chan (R) poses with his son Jaycee Fong Jo Ming as they take part in a press conference for Chan’s concert at Beijing’s Bird’s Nest stadium, April 1, 2009.

BEIJING, China — In the past, stars like Jackie Chan would be featured in cheesy 80s-style “Just Say No” videos. But now Beijing is co-opting celebrities into their latest anti-drug campaign, whether they like it or not.

This week saw Jaycee Chan, son of "Rush Hour" actor Jackie, become the latest “celebrity” paraded on TV screens, after police raided his house in Beijing’s Dongcheng district following a supposed tip-off. They arrested several men.

More than 100 grams (about 3.5 ounces) of marijuana was found in a safe in the home of Jaycee, who now faces the serious charge of “accommodating drug users,” which carries a three-year penalty, after admitting to having smoked since 2006.

In response, both Chans have gone on the offensive: Jackie has flown to Beijing to assist with his son’s case, his publicist confirmed, and publicly tweeted an apology, saying, “I feel very angry and very shocked. As a public figure, I’m very ashamed.” Meanwhile, in a bid to reduce his sentence, Jaycee has offered up the names of up to 120 fellow celebrity drugs users, Taiwanese newspaper Liberty Times reported.

Chan, the star of numerous flop films like "Double Trouble" (which garnered a UK box office of just under $10,000, according to the Telegraph), remains best known for his father — unlike his smoking partner, Taiwanese actor Ko Chen-tung, aka Kai Ko, whose hits include "You Are The Apple of My Eye." Ko, like Chan, also tested positive but will be detained on the lesser charge of marijuana use for up to 30 days.

The case has come under more public scrutiny than usual because of its uneasy mixture of celebrity glamour, the vagaries of fame in China, and the Party’s declaration of a zero-tolerance “people’s war” on drugs, in which the most talked-about casualties are prominent public figures.

These include recent meth arrests for "If You Are The One" guest Chen Wan-ning, 39, Mama director Zhang Yuan, reality star Li Daimo and "The Bullet Vanishes" actor Gao Hu.

In each case, state media has dutifully reported the apparent incredulity of fans, detailed the accused’s penitence and pointed the finger at an “avant garde” lifestyle, which “can breed spiritual emptiness, which makes them susceptible to temptations” as China Daily noted. The implication is that such celebrities are outliers, and their misbehavior an aberration in society to be made an example of.

But the public is proving increasingly cynical of such narratives — and not just the stars’ relentless crocodile tears, but the entire tone of this campaign.

The use of televised confessions, which has re-emerged as a feature of modern Chinese policing since the arrest of internet celebrity Charles Xue for solicitation, and continued with high-profile cases against the likes of GSK investigator Peter Humphrey and alleged high-class hooker Guo Meimei, has come under particular fire.

The video, with faces pixelated, showed the bust seemingly in action (“Who gave you this?” the police ask. Jaycee replies, “I’ve had it for a long time.” “That’s a lot of marijuana,” an officer observes). The footage of Ko was a “vio-lation of human rights” said Chiu Hsien-chih, a former president of the Taiwan Association for Human Rights, and opposition politicians in Taiwan have expressed concern about the judicial process.

Yu Guoming, a journalism professor at China’s Renmin University, said such confessions should only be “after a verdict has been delivered” (although with a 99.8 percent conviction rate, an arrest in China is tantamount to the same).

“It’s against the law,” Zhang Ming, a politics professor at the same university, argued on Weibo. “Even if it’s a star I really don’t like … it’s no different from public shaming.”

The police have been forced to deny the existence of a special unit targeting celebrities for PR takedowns, while speculation has been rife as to motive — particularly as Chan Sr. was not only made a goodwill ambassador for the National Narcotics Control Commission in 2009, but is a member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (which advises the National Political Congress, commonly referred to as China’s “rubber stamp parlia-ment”) and has been a controversial advocate of authoritarian rule on the mainland.

It makes political sense to “go after the conspicuously wealthy” as a sop to China’s increasingly disenfranchised, non-wealthy majority, the American Interest concluded, adding that the arrests were further evidence of President Xi Jinping “consolidating power… by thinning out the top ranks.”

But this seems rather stodgy (and Jaycee Chan is hardly anyone’s political op-ponent).

The most credible explanation might be one offered Friday in Securities Daily newspaper by entertainment venture capitalist Cao Haitiao. Mergers and acquisitions in the sector have become increasingly cutthroat, meaning companies “may be weeded out through competitive selection.” Ko, who runs a production company, has lost endorsements and was due to appear in the Tiny Times 4, a lucrative Chinese franchise.

Competing companies can attempt to nobble each other with rumors and anonymous tip-offs (this week, a bemused-looking Sohu CEO Charles Zhang refuted claims that he, too, had been detained for drugs). And who led the cops to Jaycee and Ko’s private house party? Police say it was an anonymous tip-off.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!