African migrants in Israel asked to leave the country — or report to a detention center

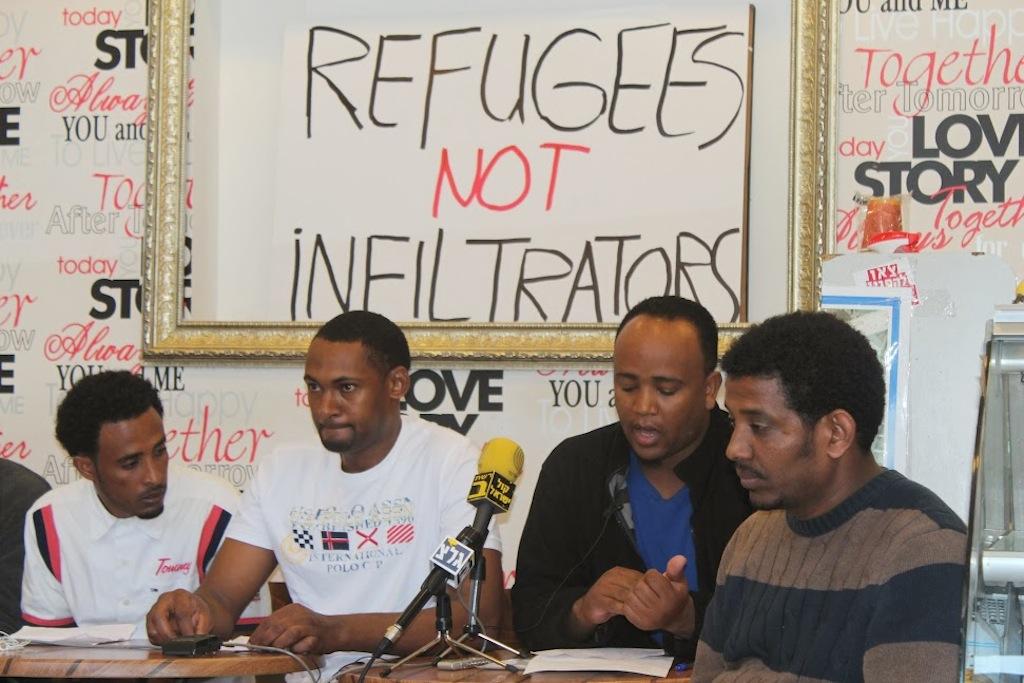

In a press conference on January 22 in a Tel Aviv cafe, the organizers of the protests—all African migrants—accused the Israeli government of neglecting its responsibilities under the 1951 UN Convention on Refugees. They called for intervention of the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and the international community to make sure Israel is reviewing asylum requests in a fair and transparent manner.

TEL AVIV, Israel — On stage, Mutasim Ali was a star. He spoke with confidence and enthusiasm, shouting slogans and sharing his feelings, igniting the thousands of fellow African migrants who gathered last Wednesday to demonstrate for refugee rights. Ali spoke of democracy, of hope and of a non-violent protest, swiftly alternating between Arabic, English and Hebrew. He spoke like a free and proud man.

In a few weeks, Ali could lose his freedom. The Israeli Immigration Authority has recently handed him a warrant. He is to report to Holot Detention Center, an open jail constructed in response to the arrival of the African migrants, within 30 days. Residents in Holot can leave but are required to return three times a day for roll call.

The migrants call Holot a concentration camp. The compound is located in the mostly uninhabited Negev Desert and can hold 3,000 people. For 27-year-old Ali, who escaped Sudan in 2009 because his “life was in danger,” reporting to Holot means he will not be able to work or maintain a normal life.

Ali is one of more than 55,000 African migrants that have entered Israel illegally in the past seven years. Most are from Sudan and Eritrea. All of them smuggled their way into the country through the land border with Egypt, which used to be porous until a fence was completed last year.

While the migrants call themselves asylum seekers, the Israeli government calls them "infiltrators," but is unable to force them to return to their countries because of its commitment to the 1951 International Refugee Convention. Rather, Israel has mostly refused to review asylum applications from Sudanese and Eritreans, in violation of the same convention, according to an Amnesty International Report.

Israel’s approach appears to be applying pressure on Africans to leave voluntary. The Israeli Immigration Authority has been offering cash payments of up to $3,500 to those willing to return to Sudan. Those who refuse are granted only temporary short-term visas and face the threat of imprisonment in the detention center. More and more of the African migrants in Israel are confronted with these two unattractive options.

Last year 2,600 Africans left Israel as part of this voluntary program.

The demonstration in Tel Aviv was part of a day of international solidarity organized by the African Asylum Seekers Committee in Israel. Protesters gathered in 13 cities around the world—including Frankfurt, London and Washington DC—to call on the Israeli government to provide freedom and rights to those seeking refuge.

The global event was the latest in a series of demonstrations organized by African migrants in Israel, as well as an ongoing hunger strike by several prisoners being held in Holot. The wave of protests is a response to the Israeli immigration authority's increasing effort to collect migrants into detention facilities.

This month alone 1,700 African asylum seekers living in Israeli cities were ordered to report to the Holot facility, according to the Jerusalem Post. But very few have done so.

In a recent interview with The Guardian, the legal adviser to Israel's Population and Immigration Authority, Daniel Solomon, said "Israel has never considered itself open to immigration on a broad scale… We see most of this group as illegal economic migrants."

But the African migrants GlobalPost spoke with dispute this claim.

Mutasim Ali said he escaped his home in Darfur because conflicts and a dictatorship regime caused him to fear for his life. Dawit Damuz and Yohanse Bayru from Eritrea left a country where extrajudicial killing, enforced disappearance and incommunicado detention are everyday occurrences.

These are the dangers that more than 55,000 other Eritreans and Sudanese in Israel may face if they go back to their countries—and the reasons why they say they refuse to return.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!