Lesnoe Ozero is a Russian language camp located in Bemidji, Minnesota.

Lots of kids are terrified their first time at sleepaway camp. I was no exception.

I was homesick to the point of moving into the bed of a girl I’d just met, and my emotional journal entries led me to believe my relentless crying kept my whole cabin up at night. It was not my finest moment.

My American camp experience had a twist — everything had to be in Russian.

Yet somehow I found myself there again the following year, and five more years after that — seven summers to be exact.

Yes, at Lesnoe Ozero, the usual lake swimming instructions were in Russian. Arts and crafts? Da.

Lesnoe Ozero is one of 15 camps offered through Concordia Language Villages, a consortium of language camps in Bemidji, Minnesota. These camps are intended to immerse kids in language and culture through a number of tactics. Some of these include daily language classes, cultural activities like using the ruble, sweating in the banya, and even being assigned a Russian name.

After traveling to Russia several times as a child, my mother, who studied Russian herself, thought it would benefit me to keep learning in the US. However, I quickly learned during my first summer at camp that my motivation for learning Russian was quite different from my peers.

Many campers shared one thing in common: The experience of adoption.

“I wanted to relearn Russian because all the time I was pushed to learn English, and Spanish and Hebrew, so I was forgetting my Russian,” says Svetlana Popovic, a camp friend who was adopted from Russia at 10. “My parents decided it would be a good idea for me to go there and not to lose my language, and just to know my heritage.”

From singing Russian songs around the campfire to learning how to play traditional instruments like the balalaika, Lesnoe Ozero was full of ways to engage with Russian culture. However, for Popovic, connecting to her heritage at camp extended much further.

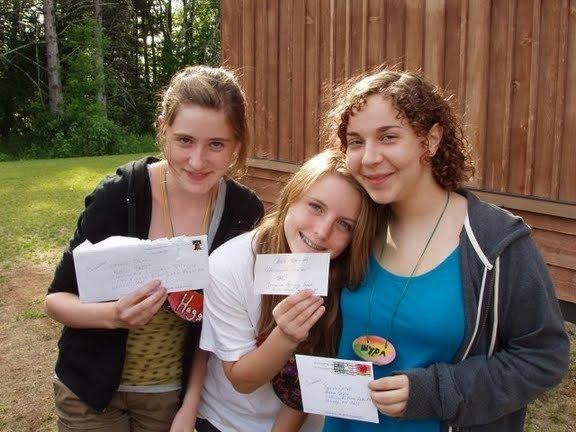

She remembers the relief that followed meeting other kids who’d also been adopted — being surrounded by people who understood.

“I felt that I had something similar to them that most of my life I had to explain to people. Where I come from, what kind of food we eat, how I have an accent,” Popovic says. “People understood you.”

For Popovic, camp was family.

This sense of community extended beyond the other kids, as most counsellors also had Russian roots. Some of them lived in Russia during the year and would travel to Minnesota just to work at camp.

After a few summers at camp, Popovic herself decided to return as a counselor.

“Teaching at camp you understand that the kids who look up to you … don’t necessarily understand where they come from. I think that’s what camp taught me and still stays with me today,” she says. “It really taught me where I come from and where I belong.”

Like Popovic , I think of camp often — this time without the tears.