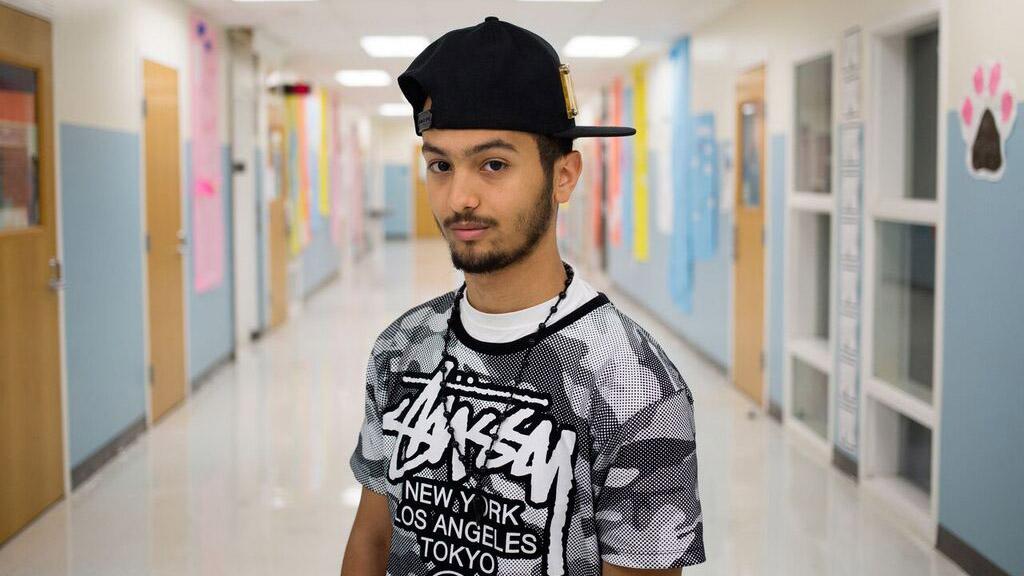

Muath Farea, 17, is an English Language Learner student from Saudi Arabia. He attends the International High School in Austin, Texas where he’s learning English with other ELL students. He’s also picked up some Spanish from his classmates, who are mostly from Central America.

Muath Farea is at a desk by himself, studying for his World History final. He’s writing in English — but that’s not his first language. So, sometimes, his teacher helps him.

"Miss, what mean this word?” Muath asks. “I still not understand.”

"The coordinates are a location of a place on Earth,” the teacher says.

“Oh, location!”

Muath is from Saudi Arabia and got to the US just months ago. He wants to learn English fast and go to college. All of his classmates at International High School in Austin, Texas are learning English, too, but Muath is one of the few who speaks Arabic. Spanish dominates, he says, although he knows of a few students here from Rwanda.

Students come to this school when they fail the state English test as freshmen or sophomores. After two years here, they’re sent back to their neighborhood high school.

His classmates are from all around the world: Iraq, Myanmar, Nepal, Rwanda. But the vast majority are from Honduras and Guatemala. That means you still hear Spanish in the hallways and in the classrooms when students don’t understand something in English. And because so many students — and teachers — at this school speak Spanish, other students, including Muath, pick it up too.

Muath says, sometimes, speaking Spanish is the only way he can socialize with students whose English is still rusty. And, he says, Arabic and Spanish can be pretty similar, too. “Like, sugar, in Arabic it’s azucar, in Spanish, azucar.”

Rosie Arrendondo, a counselor at the International High, says it’s harder for students to socialize because of language barriers. But she also sees students trying to teach each other their native language. “I’ll see kids from different countries actually hanging out together after school,” Arrendondo says. “They’re learning about each other just like any other teenager would. It’s just a little bit harder.”

Arrendondo adds that students also try to break the language barrier to help in another teenage endeavor: dating.

“I’ve had a Vietnamese student think that a Salvadoran girl is very beautiful and want to talk to her, so he goes and tries to speak to her in Spanish to see if she’ll give him her name,” she says.

Nationally, most English Language Learner students speak Spanish — around 71 percent, according to the Migration Policy Institute. And when you’re trying to learn English, hearing Spanish at the same time can make it harder. Most of the students in Muath’s English class speak Spanish. The teacher flips back and forth between the two languages.

Muath says sometimes he gets tired of this Spanglish, especially when he wants to learn English first. “I can’t focus. If she speak Spanish and after that I need focus for the English.”

It’s a problem teachers at the school recognize. Angela Hinz, an English teacher at International High, also hears from her non-Spanish speaking students about these extra language hurdles they face. “When they come to me and tell me, ‘I’m tired of hearing all the Spanish,’ I say, ‘Right.’ And I tell my students in my class, please be respectful, we have other students in the class. Please don’t speak Spanish in the class. And I tell them it advances their English.”

Hinz says because there are so many Spanish-speaking students, they have a big comfort zone, and it can take them longer to learn English than the other students.

But Hinz adds it’s not a bad thing that most students speak Spanish. She tells the other students it’s an opportunity. “It’s an invitation for you too to get curious about them,” she says. “Not just to close the door and say this is what they’re doing to me. But how can I embrace them? Because when you embrace another culture it opens up space for you to be included. You know, yeah, we have a lot of Spanish here, but there’s a lot of learning that can take place with that.”

Muath is taking advantage of that opportunity. Next year, he plans to take Spanish after school for extra credit.

How do you educate a Global Nation? Read more of our coverage of immigration and education. Then join the conversation in the Global Nation Exchange on Facebook.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!