Makmoud Nakarch rolls out dough in order to make Syrian flatbread in his bakery under a cargo train parked at Idomeni Camp.

Earlier this week, Idomeni refugee camp on the Greek border with Macedonia was a sprawling tent village that was home to about 8,500 people.

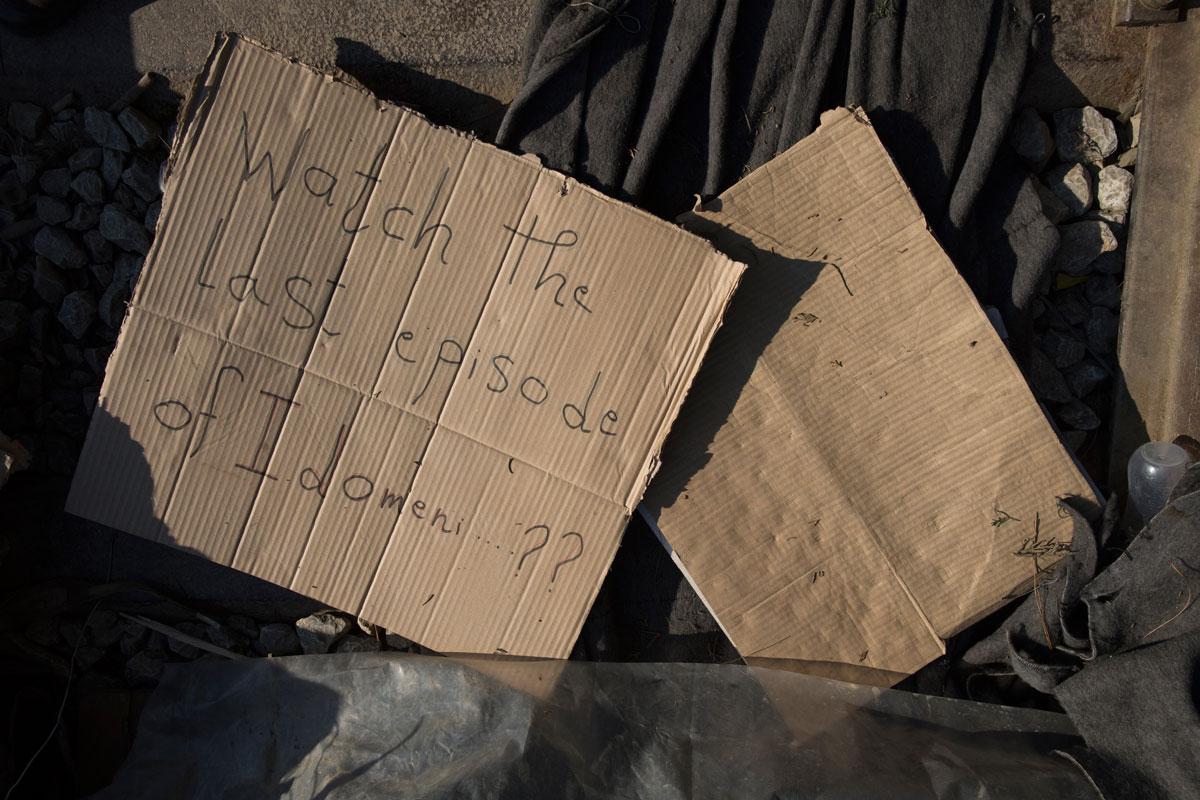

Now, after a massive police action that began on Tuesday, Idomeni is empty.

The NGOs are packing up the last of their equipment; workers are clearing the tracks at the train station where people’s tents have blocked train traffic for two months.

Pots and pans, stuffed animals, shoes and other personal belongings are scattered everywhere — a reminder of the daily life that thrived there just days ago.

Most of the population at Idomeni arrived just as the Macedonia border was closing and the EU-Turkey deal was going into effect. Their hopes of finding safe haven in northern Europe have been seriously complicated.

Three days before Idomeni closed I spoke with Makmoud Nakarch, a law student from Aleppo who had created a Syrian flatbread-baking business underneath one of the train cars sitting at the station.

He was emblematic of the can-do attitude of so many of the refugees at Idomeni. And not only did he make good bread, he read my fortune, and that of Idomeni.

Makmoud sits cross-legged on the tracks covered in flour. I watch as he forms balls of dough and rolls them out very thin on a chunk of wood using a section of pipe. His young assistant, Abdulrahman, cooks each piece on a battered metal pan over an open fire.

Q. How much bread do you make every day?

A. 300 pieces, minimum.

Q. How much do you sell it for?

A. 5 pieces, 1 euro.

He hands a hot piece of flatbread to me and one to my translator, Wisam. Makmoud shrugs an apology that he has to serve it to us plain.

Q. What would you eat it with normally?

A. Here sometimes they eat it alone but … (Arabic. Laughing.) Every good food that’s heavy food. (Laughs.)

Q. And do people like his bread?

A. Sure, I like it because it’s Syria, I smell Syria in the bread.

Makmoud arrived in Greece by boat two months ago after fleeing the war in Aleppo with his family. After the Macedonia border closed they were stuck.

Wisam is a refugee from Palmyra, and she and Makmoud talk about their discomfort with having to take handouts in the camp.

Wisam's summary: "It’s hard for us to stand and wait and take the food from persons because we don’t take anything from anyone."

So by having his own business he can make enough money to at least buy his own food and cook his food.

"Without taking anything from anyone," says Wisam.

Makmoud says he learned his bread-making skills working in a pizza place in Aleppo while going to law school. But he has other talents as well.

Wisam: He can read you as a person. We call that read your star.

Me: With the coffee or just by looking at you?

Wisam: Just by looking at you. You want that?

Me: Sure. Sure.

The law student and baker from Aleppo stares into my eyes and then into Wisam’s. He tells me I am the sort of person who “likes myself outside and inside,” which, on a good day, is true. And he tells her she has a “big purpose in life” and “loves someone far away.”

Then I ask him if he can see the future of Idomeni.

They want to pressure people here to go, to clear this camp.

His prediction was right on. Just a few days later, after a massive police action in Idomeni, the camp was shut down.

I don’t know where Makmoud is now, whether he and his family moved to an official camp, or tried to cross into Macedonia, or are in a hotel somewhere in Greece.

But his spot under the freight car where he baked bread to sell in Idomeni is empty.

Q. Does he think his family will make it to Germany or Sweden?

A. We are people who don’t give up. If we want to give up we will do that in Syria. If anyone has a goal he will reach it.

Jeanne Carstensen and Jodi Hilton are covering the refugee crisis in Greece with support from the Pulitzer Center.