Domino’s Pizza CEO delivers dose of advocacy for struggling public research universities

Over the past decade, state appropriations to flagship research universities, including the University of Michigan, have plummeted 34 percent.

In 1862, during the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Morrill Land-Grant Act, creating a national fund so states could buy land for public colleges and universities.

The goal? Make higher education available to the children of farmers and mechanics.

It was a way to repair a broken country and to set the groundwork for what America wanted to be, says historian Coy Cross.

"I would argue it still remains the most important act not only of the 19th century but I would say up until today. Some people would argue the GI Bill after World War II," said Cross. "There would be no GI Bill if we didn't have something like the Morrill Act to precede it — to open all these fields of study up and make them open to the common people."

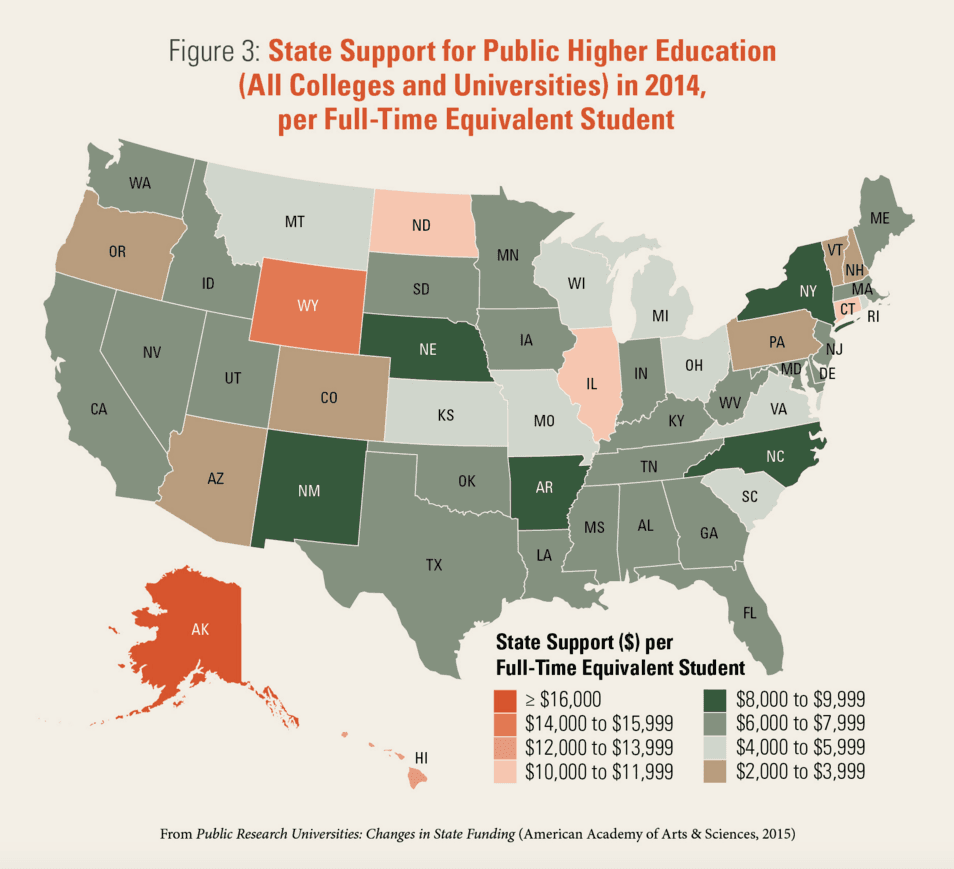

Today, land-grant universities educate 75 percent of all undergraduates in this country. According to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences' Lincoln Project, over the past decade state appropriations to their flagship research universities have plummeted 34 percent. And over the past 15 years, spending per full-time student nationwide is down 30 percent. At the same time, state increased their support of prisons by 130 percent.

Land-grant universities still serve nearly 4 million students and issue more than half of all doctorates. But increasingly, they, too, are educating only the elites.

“There is a breakdown in the intergenerational compact,” said Susan Dynarski, who teaches education, public policy and economics at the University of Michigan. “There was a promise that taxpayers would pay their taxes, students would go to school, they’d grow up and then pay taxes and support the education of the next generation. Somewhere in there that compact was broken.”

With state budgets groaning under the weight of increasing costs, says Dynarski, higher education has been the one place where lawmakers could nip and tuck.

“You can’t charge prisoners for housing. You can’t charge K-12 students. You’re stuck with the Medicaid formula. The one place where they can adjust is tuition prices, and that’s where they’ve adjusted. I think we’re going to see more of the same unless we see something different,” said Dynarski.

And what’s happening, educators say, is that a lot of middle- and low-income students can't afford a college education.

University of Michigan President Mark Schlissel says his university has tried to keep tuition down, but as the state has increasingly whittled away funding — about $100 million in the past decade — he and others have had to get creative, relying more and more on out-of-state students.

"I don't think the university is close to looking like the state it's serving," Schlissel said. "There are many explanations for that, beginning with tremendous income disparity, and great differentials and opportunities starting at pre-schools all the way through the pipeline that gets students ready to go to college."

This isn’t just an academic exercise.

Just ask Patrick Doyle, the CEO of Domino's Pizza, who has emerged as an unlikely advocate for more state funding.

.jpg&w=1920&q=75)

Speaking to higher education leaders during the 236th annual meeting of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in Anne Arbor, Michigan, Doyle said Domino's and many other businesses with headquarters and locations in Michigan are not getting what they need. And we’re not just talking about pizza-makers. Doyle needs marketing people, and the kind of business and computer geniuses that run a multimillion-dollar chain.

But Doyle says state lawmakers — in Michigan and across the country — aren’t looking at the big picture.

“When they see the universities coming [and] saying ‘We need more funding’ — that’s expected. When they see the business community saying, ‘No really, we mean it. The return on investment is there. This is a compelling place for the state to be investing.’ I think it breaks through a little bit more from a message standpoint.”

Doyle is part of Business Leaders for Michigan, a unique group lobbying state lawmakers. It includes other corporate heavyweights, including Google, Weight Watchers, and General Motors.

But some lawmakers are not moved by the business community's message.

"I think it's time we shined a light on exactly what's going on in the expense side of the equation before we're talking about putting more and more extra dimes of public funds into the mix right now,” said Michigan State Senator Patrick Colbeck.

Colbeck opposes any boost in funding for the state’s public colleges and universities. He says that after the Great Recession, public universities can't just request more state money and expect to be trusted to spend it wisely.

"Everybody would like to be where they were before the Recession. Property values would like to be where they were before the Recession. It doesn't work out that way."

Educators and business leaders, though, worry states like Michigan are starving what was once one of their greatest resources for talent: the land-grant university.

"As a country we are blessed with a public university system in the United States that is unequaled in the world," Doyle said. "But it's at risk if we don't turn it around — if we don't recognize the centrality of that system and how it's going to continue to make the country prosper."

This story was produced by On Campus, a public radio reporting initiative focused on higher education produced in Boston at WGBH.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!