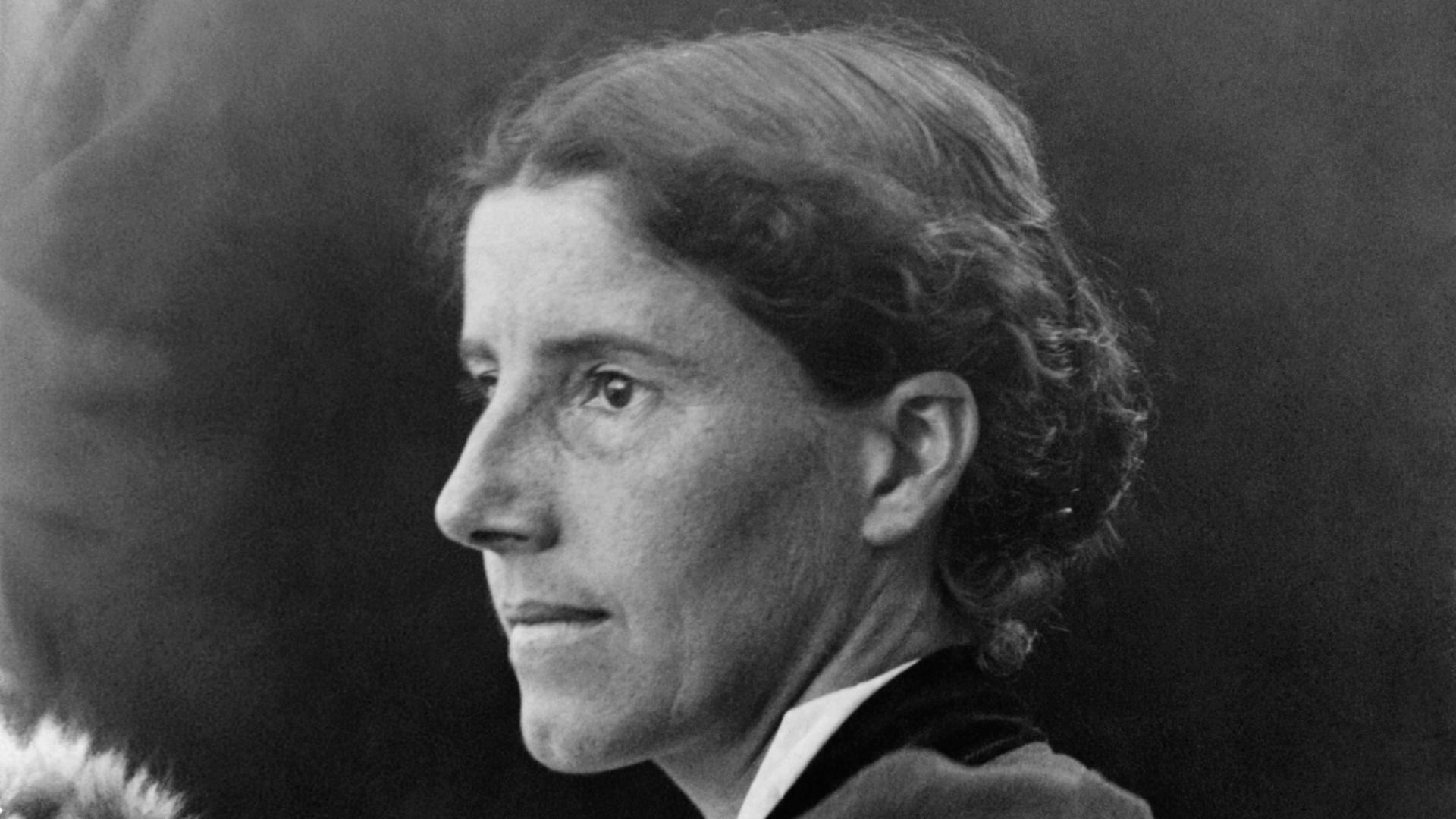

Charlotee Perkins Gilman, circa 1900.

“They had had no kings, and no priests and no aristocracies. They were sisters, and as they grew, they grew together — not by competition, but by united action.”

This is how Charlotte Perkins Gilman described the utopian all-female community "Herland" in the book of the same name, published in 1915. Gilman, best known for her book"The Yellow Wallpaper," was a trailblazing feminist, suffragist and publisher. Her progressive views on everything from postpartum depression to euthanasia to gender-neutral toys were so forward thinking, they could probably be printed in Lena Dunham’s edgy newsletter today.

But even Gilman couldn’t have foreseen that 100 years after she wrote her sci-fi novella about a feminist paradise deep in the jungle of a distant continent, the hive-mind of the internet would decide to bring it to life.

“It wasn't just ‘Oh, here's a book. Let's pretend we're in the book.’ It's using the book as sort of a design document,” says Kate White. She’s a pioneer of Herland, a Facebook group of over 5,000 members interested in creating an eco-commune in South America inspired by the “land without hims” that Gilman described.

The biggest difference between the movement and the book? The pioneers insist this Herland isn’t just science fiction.

In May, White is giving up her apartment in Fresno, California, and heading south in the truck and camper the group purchased after two years of saving.

She says once she reaches South America, by road and ferry, she will meet up with a handful of European Herland pioneers. Their ultimate destination is somewhere in the jungle on the border of Guyana and Venezuela.

“It is an area that is uninhabited so we're not pushing anyone out. And it's warm enough that we don't have to worry about freezing and those sorts of things. So it's a very friendly area for living,” White says.

The Herlanders won’t say exactly where it is — just that they’ve secured an agreement with the relevant government.

White says once they arrive, they’ll set down and start building, making room for the 100+ second-wave Herlanders from around the world who will help “set an example for the world in general that it can be done. That people can get together and live in harmony.”

The idea of an eco-feminist commune may sound radical, but it’s actually nothing new. In the 1970s and '80s, separatist communities known as “womyn’s lands” sprang up throughout the rural US and Canada, inspired by the women’s liberation movement.

Crissa Cummings has been a resident of one of the last of these communities — SuBAMUH, the Susan B. Anthony Memorial Unrest Home — for the past eight years. Located on 150 acres of forested land in rural Ohio, SuBAMUH was established back in 1979. It was a time when “jobs were still listed in papers as ‘women's’ jobs and ‘men's’ jobs. So a lot of it was just taking a look at the way oppression was affecting women,” Cummings says.

But in an age when Caitlin Jenner is on the cover of Vanity Fair and Hillary Clinton is a leading candidate for president, women-only communities may be losing their appeal.

“Most of the womyn's lands in the country either have no residents or only a single resident,” Cummings says. (SuBAMAH has five.)

For Herlanders like Kate White, however, not much has changed since 1979 — the man is still the man.

“For every step we fight to go forward [women] get pushed backwards further. There's only so much freedom that they will allow us to have,” she says.

According to Cummings, when you’re living on a feminist commune, “freedom” isn’t necessarily the operative word.

“I will say that having it be women-only can be very challenging. I struggle with how it limits my ability to have male visitors here,” she says. “It's a lot like being in a marriage, quite frankly.”

The feminist utopia Gilman describes in the book "Herland" lasts for 2,000 years. For me, standing next to the truck parked outside White’s apartment in Fresno, it’s still an open question whether this Herland will get off the ground.

But for White, at least, there’s no turning back.

“This has been my dream all my life,” she says. “People don't plan on giving up their dreams and I don't. I don't plan on coming back.”

As Charlotte Perkins Gilman once said, “To attain happiness in another world we need only to believe something, while to secure it in this world we must do something.”

The article you just read is free because dedicated readers and listeners like you chose to support our nonprofit newsroom. Our team works tirelessly to ensure you hear the latest in international, human-centered reporting every weekday. But our work would not be possible without you. We need your help.

Make a gift today to help us reach our $25,000 goal and keep The World going strong. Every gift will get us one step closer.