A year after Freddie Gray’s death, kids turn Baltimore’s uprising into art

This graffiti tribute to Freddie Gray was spray-painted on one of the buildings in Gilmor Homes, the West Baltimore housing project where the 25-year-old man last lived before dying while in police custody.

A year ago, Devin Allen was virtually unknown. Last May, he landed on the cover of Time magazine for his photography of the Baltimore uprising following Freddie Gray’s death. This month, he launched his career as a community artist and educator.

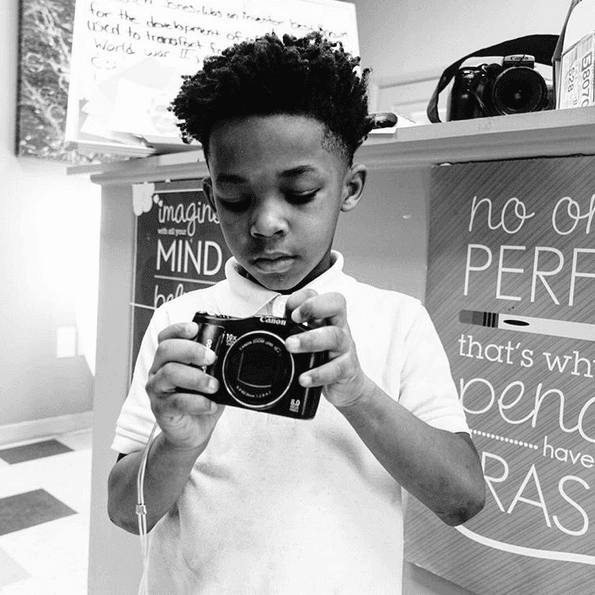

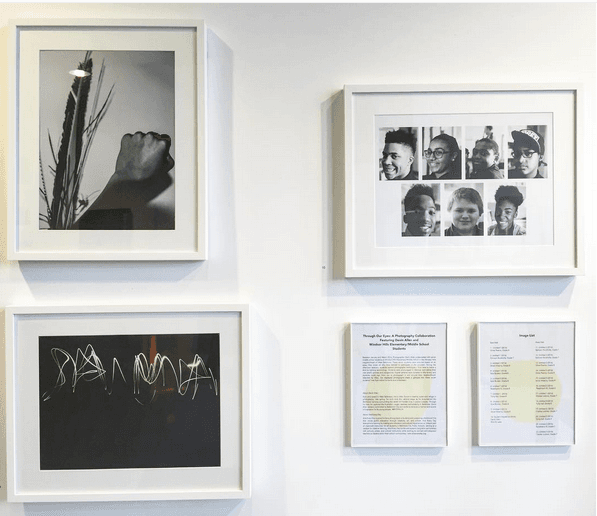

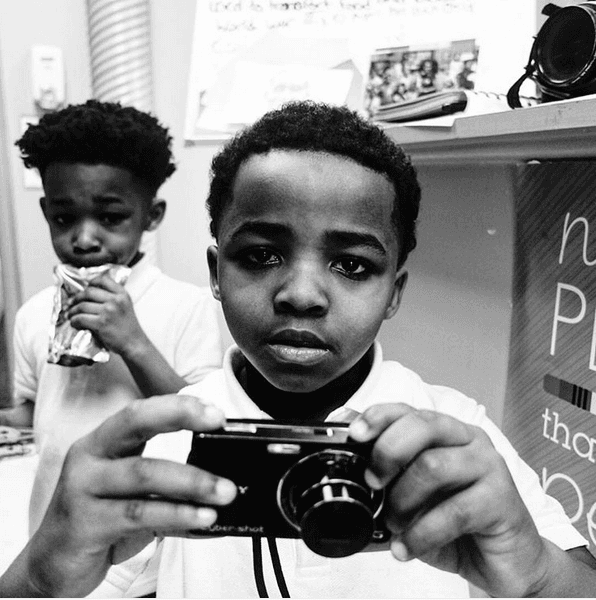

“Through Their Eyes,” a collaboration between Allen and a local school, showcased photography by Baltimore youth whom Allen had mentored. Allen sees what’s possible in Baltimore — a city long plagued by poverty and violence — especially using art to uplift the city’s youth. Since his first solo exhibit in July 2015, the West Baltimore photographer estimates he’s given art presentations to more than 2,000 students at various events.

“This is the most important thing I can do,” Allen says.

The numbers show art matters: A study of Missouri public schools found that increased art education resulted in fewer disciplinary infractions, as well as higher attendance, graduation rates and test scores.

But the percentage of students of color receiving an art education has declined: by 49 percent for black children and 40 percent for Hispanic children from 1982 to 2008, according to the National Endowment for the Arts. For white children, it dropped just 5 percent.

With Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan proposing millions of dollars of cuts to Baltimore school budgets next year, local art advocates worry the arts will be hit hardest. That’s where artists and nonprofits come in: to fill in the gaps. The Reginald F. Lewis Museum in Baltimore connected Allen with local students by featuring a free exhibit of his work and inviting local schools for field trips.

“Even before the uprising, we wanted a place for the community that was free and open to the public so we could engage the public on topics of the day,” says Helen Yuen, the museum’s director of marketing. “After the uprising, we realized that vision. When Devin Allen’s photos went viral, we realized that his photography was a perfect fit.”

But Allen wasn’t satisfied being a motivational speaker alone. He wanted to teach students — especially ones who grew up in neighborhoods like his — how to take photos. Over the summer, Allen fundraised on his own to buy cameras and hold youth photography workshops. He started at Kids Safe Zone, a drop-in community center where he still teaches. But he was hoping for a chance to teach a longer, more focused workshop. When Cindy Marcoline, a librarian at Windsor Hills Elementary-Middle School in West Baltimore, asked the RFL Museum to recommend a teaching artist, they referred Allen.

Allen ended up mentoring seven middle-school students over the course of three months. Their work is now on display at the Motor House, a local arts venue and home to Arts Every Day, a nonprofit that partners with the school and helped cover the costs of the workshop and photography show. He says the experience has inspired him to continue collecting cameras and teaching children throughout Baltimore.

Marcoline says that arts education can be hard to come by — especially with Baltimore school budgets. That is why a Title I, or high poverty, school like Windsor Hills depends on artists and arts organizations.

Arts Every Day partners with 35 other Baltimore city schools and reports reaching more than 17,000 students through artist residencies, field trips and performances. Eighty percent of these schools are designated Title I.

A local artist who goes by the name C. Harvey wants to see young, black artists flourish. Prior to the uprising, she says, many black Baltimorean artists like her felt ignored. Now, the 28-year-old helps Baltimore youth sell their art online through her organization, Baltimore’s Gifted. Harvey believes that local institutions tend to favor white, outside artists like those from the Maryland Institute College of Art, an elite, majority white, private art school that attracts many non-Baltimoreans.

“It’s like Baltimore doesn’t know art outside of MICA,” says Harvey. “Oftentimes, we get completely passed over.”

That’s one of the reasons why Allen’s rise to acclaim is so notable. He is a young black man from a working-class family in a city that rarely provides opportunities for local artists who lack formal training. He is the exception to the rule. That is also why it is so important for Baltimore children in public schools — 82.7 percent of whom are black — to have a creative role model like Allen.

“He identifies with them a lot,” says Julia Di Bussolo, executive director of Arts Every Day. “Their struggles with school, their struggles on a day-to-day basis.”

Hence the need for community arts outreach. Harvey thinks such a shift must come through legislation. “You can’t just blame Baltimore’s problems on poverty and [lack of] education,” she says. “At some point, you have to blame the people creating policy.”

Di Bussolo says it’s important to remember that the Baltimore uprising did not happen simply because of Gray’s death, but because of other frustrations affecting the city’s black youth in particular.

“To understand the uprising, you need context,” she says. “There are so many layers. There’s so much more to the story as to why anything would happen in the first place, even before Freddie was arrested. There’s a reason why [his death] struck a chord. There’s a reason why that blew up the way it did.”

Di Bussolo believes artists and arts educators can help children connect with one another and reflect — not just in Baltimore, but everywhere.

This story was originally published by YES! Magazine, a nonprofit publication that supports people’s active engagement in solving today’s social, political and environmental challenges.