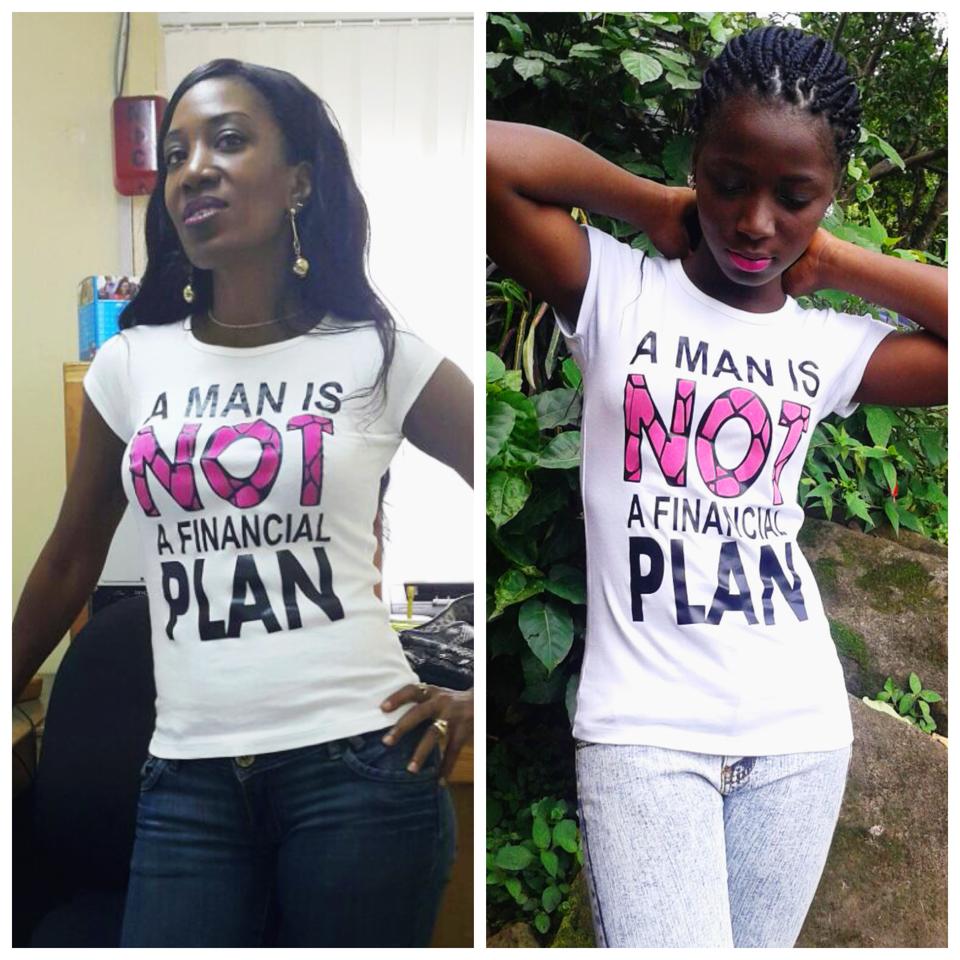

Vickie Remoe in Accra, Ghana. Her shirt bears the slogan of a social media campaign she runs: "A Man is not a Financial Plan."

Vickie Remoe was born in Sierra Leone, but her family left during the civil war in 1997 when she was 12. She went on to get an undergraduate degree at Haverford College in Pennsylvania, and returned to start the Vickie Remoe Show.

She got to travel with the president’s press corps and became well-known on television. But in her four years making a go of it in local media, she says, she also got a crash-course in being propositioned.

When Remoe would pitch her TV show to potential advertisers, she found the executives she met with were receptive, but not necessarily to her pitch. Advertisers would say, “'This is a very good idea, these are the kind of ideas that we are looking for — you're a very smart woman,’ and then the next thing that would come out of their mouths would be: ‘You know, we should go to lunch and discuss these things further,’” she says.

When she first started getting these invitations, Remoe says, she’d assume they were just part of doing business. “But eventually I realized that they were so not interested in my show, they were only interested in me.”

Remoe started to dress differently, wearing her grandmother’s flowing gowns — called “boubous” — because she thought that covering up completely would change the way men approached her. No dice.

“The thing is, it wasn't about me as an individual. It wasn't that I'm so attractive. It's that … as a young woman, everything lies in your ability to seduce men,” she says. Still, “even when the guys were going really extreme in terms of their advances, you can't flat-out curse somebody out — which I would do if I were in the US — because it's a very small [business] community.”

The turning point

Remoe says the turning point was when a finance executive invited her to meet a higher-up from his bank — in what he described as a meeting of entrepreneurs in Sierra Leone.

"I come there and I sit down, and I see another lady there whom I know to be, not necessarily a lady of the night who walks the streets — but definitely, she's a higher-class call girl,” Remoe recalls. After the people she thought were other guests left, she realized there were no entrepreneurs: she’d been ambushed into a double-date.

“So we go out to dinner, and it's, like, champagne, lobster — this gentleman is doing everything he can to impress me," she says. "‘Where do I want to go, do I want to go to Dubai, when am I coming to Lagos?’”

Remoe says she avoided his advances, eventually, saying, "‘I really am not interested and I want to go home,’ and I was dropped off." But it reminded her forcefully that “at any moment you could be in a situation that reminds you that … you're ‘just a woman.’”

Eventually, Remoe abandoned her career in Sierra Leone for graduate school in New York.

“I left Sierra Leone incredibly, incredibly frustrated that while I loved Sierra Leone so much, it wasn't necessarily ready for me as a young woman who wasn’t married, who didn't have a sugar-daddy who could speak for her.” After studying at Columbia University in New York, Remoe decided to move to Ghana, where she knew she’d find a tight-knit community of young entrepreneurs.

She now handles marketing for some of Ghana’s leading companies.

In response to the challenges she faced at home in Sierra Leone, Remoe mentors high school students as part of a social media campaign called GoWoman Africa.

“One of our slogans is 'A man is not a financial plan.’ In fact my phone case says ‘A man is not a financial plan,’ I have T-shirts that say ‘A man is not a financial plan,’” she says. “Because I realized this idea of us being shipped off to men to marry us, or being married and having a man bear your financial burdens and provide for you, plays a huge role in the way women see themselves, and also in our relationships with men.”

The reaction to the campaign has been mixed. “When I was in Sierra Leone two weeks ago, I wore the T-shirt, I was walking in the street and a man actually looked at me and said he was going to tear the shirt, what am I trying to say, am I actually trying to say that I don't need a man? Who do I think I am?”

Young women have been more receptive: “Before GoWoman, the women's discourse space in Sierra Leone was mostly dominated by women in their 50s and older. Now young women my age are forming their own groups and getting involved,” she says.

Remoe publishes a women’s magazine called GoWoman to talk about women’s experiences in Sierra Leone. The most recent issue was dedicated to women's role in the fight against the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone, says Remoe. “It brings me joy, because I feel like I'm doing something about a problem that for the most part people don't recognize.”

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!