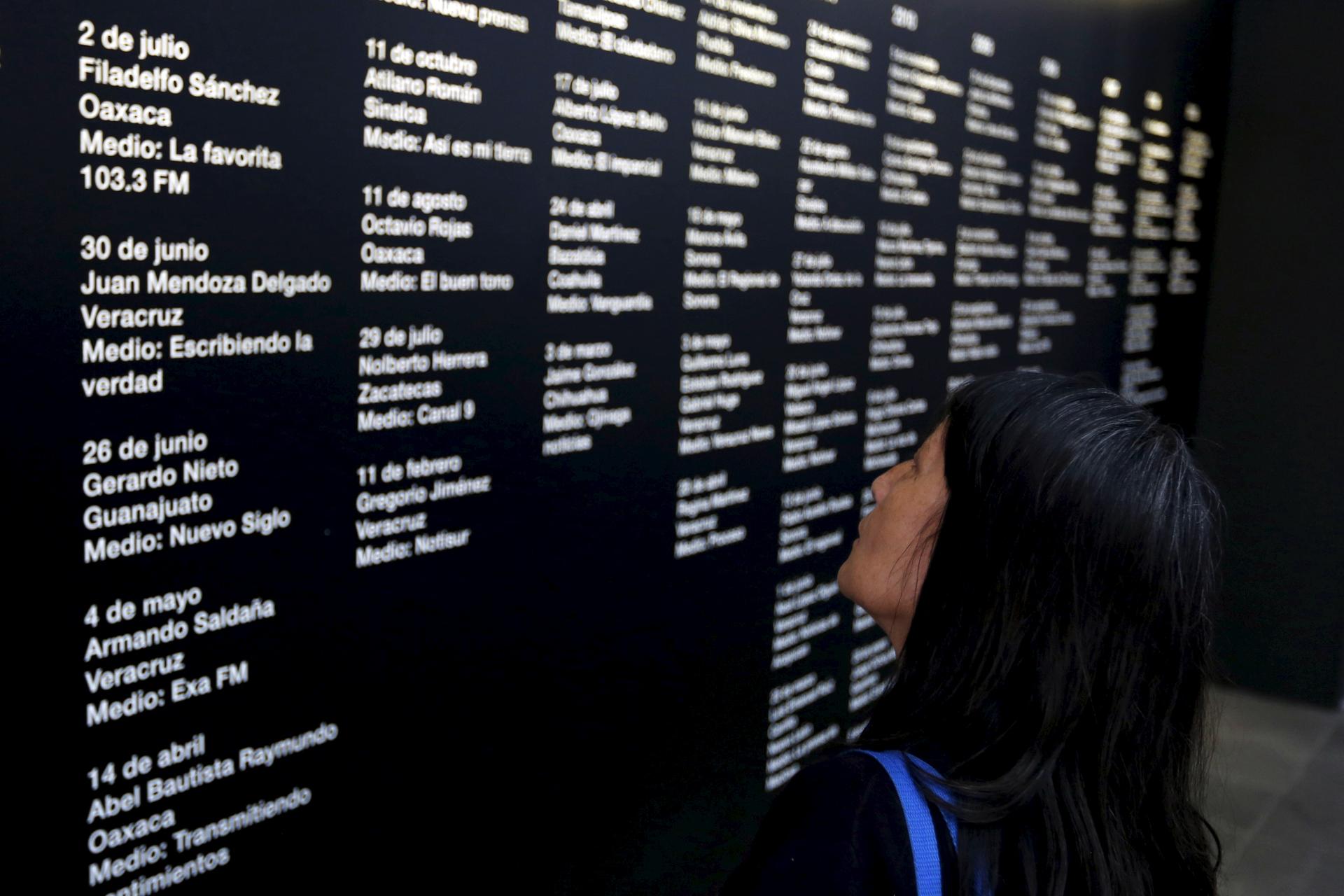

At a museum in Mexico City, an exhibit memoralizes Mexico's killed and disappeared journalists. The displays names 89 journalists who have been killed between 2005 and 2015.

She was 27, a mother of two, and this week she became the latest journalist murdered in Mexico, continuing a dark story of crimes against the press in a country grappling with entrenched cartel power.

Early Monday morning, a group of armed men reportedly wearing military uniforms dragged Anabel Flores Salazar, a reporter in the Mexican Gulf Coast state of Veracruz, from her home near the city of Orizaba. They claimed to have an arrest warrant, but it is unknown for what. After being carried off, her family tried to find her, but couldn’t, until she was found dead alongside a highway in the neighboring state of Puebla. She was bound with a plastic bag over her head.

For years, Mexico has ranked as one of the world’s most dangerous places to report, as reporters are put in the crosshairs of powerful criminal groups. They also join those who face similar danger: human rights advocates, lawyers and average Mexicans who happen to get caught in the line of fire.

But over the past decade, Veracruz has become particularly toxic. Flores Salazar’s death adds to a growing list of journalists killed in the state, with at least six reporters killed there since 2011 because of their work, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). The CPJ adds that it is investigating the deaths of another seven journalists in Veracruz, along with several more who have gone missing.

What is happening in Veracruz? It’s complicated, like other places in Mexico riddled with crime and corruption, but there are a few reasons that make Veracruz stand out now. One is that the Zetas cartel, one of Mexico’s most ruthless groups, has anchored itself in the state and is currently fighting rival gangs. Gangs fight hard to control key routes for smuggling drugs and migrants, and they are also dedicated to kidnapping and extortion at every level of business. The ensuing violence is steady and gruesome. It is common to see headlines from Veracruz about mass graves, with little reason given for the deaths.

Regarding journalists, we see a disturbing pattern from the state government, led by Governor Javier Duarte, who took office in December 2010. Often, within hours of news of a dead journalist, officials from his office condemn the reporter, alleging ties to criminal groups. This happened in the case of Flores Salazar and, once again, hard evidence of those ties has yet to be presented. But the damage is done: The journalist’s reputation is tarnished even before the investigation begins.

Why respond like this? It is unclear, just as it is unclear why one journalist can be targeted over another. But Governor Duarte himself has been tied to the Zetas gang, something he strongly denies. There is also the reality of collusion, either by fear or greed, between cartels and politicians and law enforcement officials in Mexico.

Whatever the case, what we do not see in Mexico, neither at the state or federal level, is an out-of-the-gate condemnation of the attacks against journalists and the erosion of press freedom in large swaths of Mexico.

Yet journalists do speak out. After Flores Salazar’s death, her paper, El Sol de Orizaba, published a front-page editorial condemning her murder and the impunity in the state. Another local paper published a letter to government officials demanding that they do more to protect journalists and punish criminals. The CPJ also urged the “Mexican federal government tot put an end to this cycle of endless violence by bringing the perpetrators of this crime to justice.”

There was also national outcry last July when Rubén Espinosa, a freelance photojournalist, was executed mafia-style, along with four women, in a Mexico City apartment. He said he had left Veracruz after receiving threats from officials in Veracruz for his reporting, which often emphasized the frustration people in the state felt over high crime levels. Shortly before leaving Veracruz, Espinosa had also organized other journalists to place a small plaque outside the state government offices to commemorate a slain colleague. Soon after, Governor Duarte lashed out and called reporters “bad apples” that would soon fall.

Until things change, journalists who remain in Veracruz, like in other parts of Mexico, will remain vulnerable as they work. And they will re-evaluate why they continue to report. Many will continue protecting themselves through self-censorship, simply avoiding risky stories or omitting their bylines or the names of cartels to avoid aggravating criminals.

Tuesday, one journalist in Veracruz, who requested anonymity, said, “I feel passionate about what I do, knowing that I can inform myself and others about what’s going on in my own backyard.” But he feels increasingly tested. He knew Flores Salazar, and has received several threats for his work. “But this is my home, and I do take pride in my work,” he said.

When asked what else he would do besides report, he said jobs were scarce and that he would probably work at a grocery store or become a carpenter.

Read a recent article by Monica Campbell about journalism in Mexico for the Nieman Reports. The article is also available in Spanish.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!