For Hong Kong dissidents challenging China, ‘it feels like 1984’

In this June 2014 photo, Hong Kong artists walk with photocopies of the Beijing white paper "One country, two systems" stuffed in their mouths to symbolize Chinese repression of free speech in Hong Kong. At the time, more than 200,000 people voted for full democracy in Hong Kong within the first few hours of an unofficial online referendum.

An unsettling question now troubles Hong Kongers who routinely denigrate China’s Communist Party.

Could I possibly get abducted?

Their paranoia is well founded. From Kenya to Thailand, Myanmar to Hong Kong, people who’ve angered Beijing have been snatched up without a trace.

These abductees, none of them residents of mainland China, nevertheless resurface in China proper. They simply pop up in police custody — often suddenly repentant, as if reading a script written by their captors.

Or in the case of Gui Minhai — a Hong Konger with Swedish citizenship and a habit of publishing scandalous books about party officials — confessing his sins on Chinese television after vanishing late last year from a Thai beach town.

Through sobs and sniffles, he told the cameras that “going back to my country and turning myself in was voluntary.”

That is the line from Beijing, too. But few are buying it: not many Hong Kongers, and not the European Union, which calls political kidnappings the “most serious challenge” to Hong Kong’s identity.

Though technically part of China, Hong Kong is a semi-autonomous territory with separate laws allowing residents to mock elites in Beijing — a privilege their mainland cousins do not enjoy.

Now Hong Kong’s mishmash of artists, activists and lawmakers who frequently criticize the Communist Party feel their independent streak is being rubbed out.

On Tuesday, heavy security lined Hong Kong streets as a senior Chinese official began a three-day visit to the territory. Demonstrators managed a small protest, and at least seven were reportedly arrested.

The recent abductions are a “game changer,” says Kacey Wong, a provocative Hong Kong artist. The televised confessions, he says, “totally remind me of those POWs in the Vietnam War. You know, force the soldiers to confess in front of cameras. Totally treat them like war criminals.”

Wong, 46, has made ridiculing Chinese authoritarianism into an art form. He once constructed a towering crimson giant, emblazoned with a yellow star — emulating the Chinese flag — and led it through Hong Kong’s streets like a red menace descending upon the city.

“What’s happening here now, we’ve already seen it happen in Tibet,” Wong says. “You never know when the next purge will happen. It feels like 1984.”

This sort of foreboding speech is becoming more common in activist circles here. But there is a mounting fear, Wong says, that Hong Kong’s population is too docile to rebel.

The city’s 7 million inhabitants have much to lose. The island territory’s per capita GDP rivals that of Japan. Though bustling, it is free from the lung-searing smog that curses many Chinese cities. Its people often speak freely, having evaded the trauma wrought by the bloody ideological crackdowns that cowed many mainlanders into obedience.

Yet many in Hong Kong — a British colony until 1997 — are nevertheless stuck in a mentality nurtured by imperial rule, according to Wong. He doubts the workaday bankers and administrators who keep the city humming will do much to resist Beijing’s encroachment on their freedoms.

“We’re like the best servants,” Wong says. “Like Batman’s butler, you know? We’re cultured. We can communicate. We look good and we’re fast and efficient. But in the end? You’re just a slave.”

Not all dissidents share his dark humor and despair.

The most visible force against Beijing’s dominance is a student-led vanguard — the driving force behind the Umbrella Movement that occupied Hong Kong’s streets in late 2014.

China’s government cast that movement, determined to stop Beijing from hand-picking Hong Kong’s leader, as a militant uprising. As one propaganda video warned at the time: The protests amounted to a “knife in the heart” of Hong Kong that could “kill this city.”

The movement neither killed the city nor liberated it. But many of its most strident protesters have coalesced into new political parties that aggressively demand more autonomy — while sometimes hinting at the possibility of outright independence.

Among them: a party called “Demosisto,” which derives its name from the Greek words “people” and “resist.” It is fronted by Joshua Wong, the teenage Umbrella Movement campaigner nominated by TIME magazine in 2014 for “Person of the Year.”

“We have to let people know the importance of fighting this regime,” says Agnes Chow, Demosisto’s deputy secretary general. At 19, she divides her time between university exams and political resistance.

“This regime is trying to take away our basic freedoms and, now, our own personal safety,” she says. “It’s time for all the people living in Hong Kong to stand up and fight back.”

Activists in Hong Kong were particularly shaken by the December abduction of Lee Bo, 65, a vendor of thinly sourced, scandalous books about communist officials. He was yanked right off the streets of Hong Kong. After his abduction, Chow declared that “Hong Kong is not Hong Kong anymore.”

Demosisto members assume their calls and emails may be monitored by Chinese agents, Chow says, and they try to discuss delicate matters only in person. Abduction, she says, “may happen to anyone who fights for justice or does so-called ‘sensitive’ things.”

But Chow is not entirely jaded. She says the Umbrella Movement taught her that many Hong Kongers with comfortable lives will donate cash and cheer on the pro-democracy camp — even if they might not face down police in riot gear.

Meanwhile, Hong Kong’s student activist core seems even more feisty in the wake of the failed Umbrella Movement protests.

A new crop of parties — with names such as “Youngspiration” — have appeared to push for “self-determination” or even a referendum on independence.

Suggesting the possibility of a Scotland-style independence vote is about as far as they can push without inviting Beijing’s wrath. There is one new party advocating outright separation, but it is secretive; China’s state-run papers dismiss it as a “practical joke.”

Chow is not adamantly insisting on independence for Hong Kong. “Of course, I believe that if we can gain democracy under the rule of China … it’s a good thing,” she says. “But if we can’t see this hope in the future, maybe Hong Kong people will choose another way out. I don’t know.”

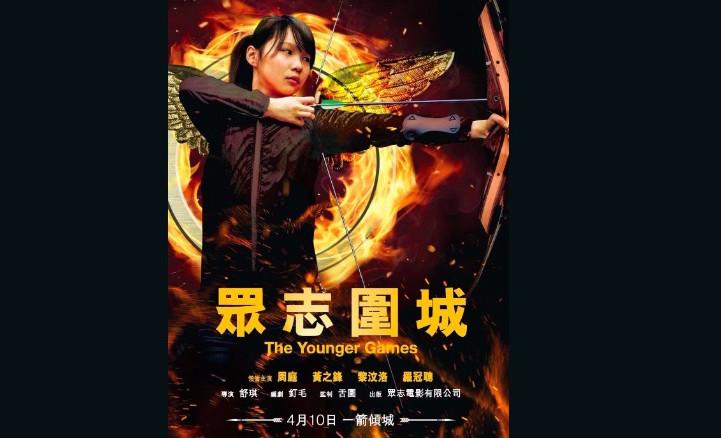

The message conveyed by her party’s online advocacy is less subtle. Demosisto has circulated a photo of Chow, surrounded by flames, gripping a bow and posing like Katniss Everdeen — the young heroine who toppled an authoritarian regime in "The Hunger Games."

This story was reported from Hong Kong.