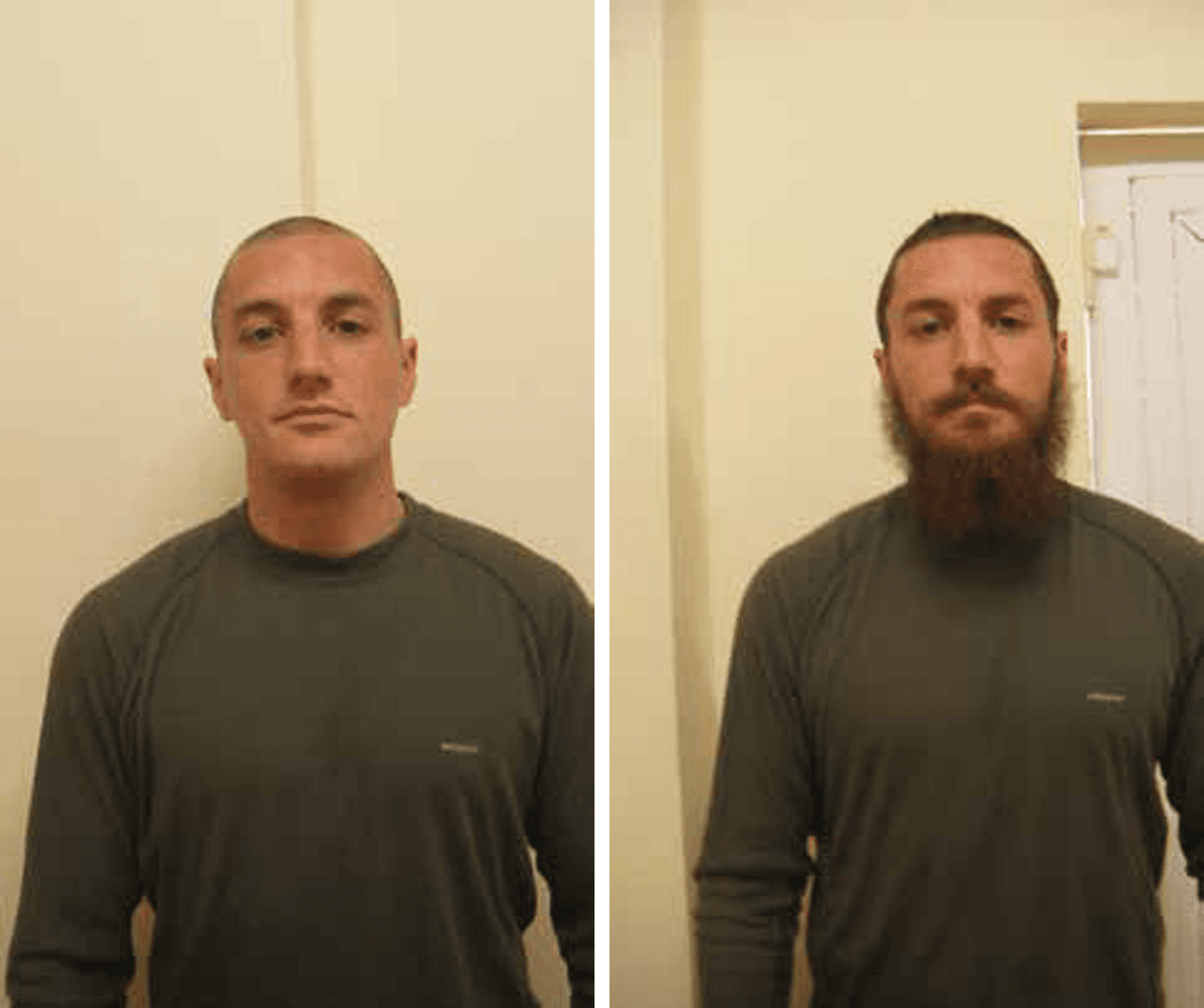

Waiting for someone inside a former Taliban-reinforced cave.

Douglas Laux was a steelworker's son at a college in Indiana when he applied to the CIA. A few years later, the 20-something was dropped into the back of beyond on the Afghan-Pakistani border.

"The second I touched down I realized I don't know what the hell I'm doing,” he says.

Laux left the agency three years ago and wrote the memoir "Left of Boom: How a Young CIA Case Officer Penetrated the Taliban and al-Qaeda."

He says his first surprise was realizing the language skills the agency taught him didn’t work on the ground.

"I was trained in Pashtu. I walked out the door with a [score of] three on the government scale which means you're fluent in reading and writing the language," he says. "But once I got [to Afghanistan] I realized, 'Hey, the word that I used for car is not the word they use for car.’ So it was a trial by fire."

Although the CIA has censored Laux’s book, he was able to include some of his criticisms of the agency.

At one point you get to know an [Afghan] warlord who helps you by calling in the location of an al-Qaeda operative. That operative is then [allegedly] killed in a drone strike. As someone who works for an intelligence-gathering agency, wouldn't it have made more sense to capture and interrogate the suspect? And how do you feel when that happens?

Not terribly good. Now I will point out for your listeners, you said "drone strike." I did not say that. I don't write that in the book. That's you reading between the lines.

For me, being a human intelligence operator, I had lot of questions about it. And I wondered, "Why not collect on this guy? Why not try to penetrate his network? Why not get somebody inserted who can get all of the secrets to know what the next attack is going to be?" Because the moment this person died is the moment we lost that opportunity.

So I do want to challenge the narrative in that — what are we supposed to be doing? Are we supposed to be so paramilitaristic in eliminating high-value targets? Or, should we be trying to penetrate their networks to learn what they're gonna do next? I think the latter, but again that's just my opinion.

Sections of your book are censored by the CIA. The agency reviews all books by former CIA employees, and redacts or censors information it considers sensitive. But you've left the black bars in the book. I'm going to guess that in some of those sections you're talking about the role of the Pakistani intelligence service, which is presumably helping to make the bombs the Taliban uses. That's what we've heard. Why can't their story be told?

It's an excellent question, and it's the exact reason I've left in the black bars. It's to show, "Hey, this is what I was able to talk about. This is what the US government is comfortable revealing, and this is what they're letting you know, and this is what they told me I couldn't talk about."

And obviously you can tell I'm not trying to be dodgy with you or cagey. I just have to be very careful because I've been censored. You know what you saw that was blacked out.

You say it's Pakistan. I don't say it's Pakistan.

Since the Congressional Torture Report came out there's been a lot of soul searching about what the purpose of the CIA is. What do you think it is?

Well, the role of the CIA is what it always has been since its inception: to collect human intelligence. They still do that, and they do it better than anybody else in the world, rest assured. And, you're right, there's been a lot of mistakes over the last 15 years. You want to talk about human torture, we stopped that. It stopped before I ever even joined. It was a mistake, and it was mess, and I'm not proud of it. I'm really glad that it stopped.

You call your book your "trial by fire" into the CIA. But it's also an introduction to the agency, national security and its slippages. Are you the exception to the rule of CIA field operatives, or is your story pretty typical, you think?

Probably, there's a lot of folks like me who have gone through some of the same stuff, some of the same hardships. Let me tell you, it ain't easy. If you ever can get used to having six different names and answering your phone in five different languages, lying to everybody who loves you most, then you're a stronger man than me.

Let me ask you about that stress and how you dealt with it, because you describe your battles with substance abuse, alcohol, oxycontin. Were you able to hide that from your bosses at the agency?

Yeah, I was, to a degree. I mean, I don't know. The guy that I admired the most, I call him "bossman" in the book, he was my boss, he knew immediately.

He knew I wasn't right. He knew I wasn't of sound mind because he had seen me at my best, and he was seeing me at my worst. And he knew on the second that I was struggling and I had an addictiion problem. And you know what? He's also the one who saved and told me, "You gotta stop this. What are you doing? Get your stuff together."

And I'm very thankful to him.

If your story is business as usual at the CIA, not just substance abuse but the Pashtu lessons, the whole thing, what kind of liability is this for US foreign policy? What have we failed to achieve because this is the way the agency is?

Look, if you read my book, and you look at the agency as a failure, then I have failed. I hope that people read it and go, "Man they could be incredible, but — "because of the reasons that I lay out. It should be viewed as, "We are trying, and if you see it as a failure, OK. Please offer us a solution, and we're going to keep moving forward with that, too."

Don't ever forget that CIA is not staffed by robots yet. It's still red-blooded humans doing everything they can.