Matilda Moses sells tomatoes in Tudu Market, part of a sprawling district of open-air and covered markets in central Accra. She can make the equivalent of 300 dollars in sales in a good week.

Ghana is one of only a handful of places where women are more likely to start businesses than men.

There are corporate-feeling malls and glossy supermarkets popping up all over the West African country. Still, more than 90 percent of people here still do their almost all their shopping at open-air markets, where the stalls are dominated by women, each running a small business.

It’s an encouraging trend, but behind this bright statistic is a troubled history: during Ghana’s military coups of the 1970s and 1980s, market women became the target of government terror, blamed for an economic crisis gripping the country.

To understand why that could have happened, you have to first see the market women’s power in action.

Haggling as a sales strategy

Take Matilda Moses, who sells what many consider the finest tomatoes in Accra’s Tudu Market. Her stall is small — a plywood tabletop balanced on an old crate — but she can make the equivalent of $300 in sales in a good week. It’s a tough business, Moses tells me in Ga, the language she speaks: “It can cost you, but it can make you good money.”

Some of Matilda’s customers come from middle-class neighborhoods close to the new supermarkets. But they choose to go out of their way to come here. “Her tomatoes attracted me,” says customer Grace Nortey.

While the produce in supermarkets tends to be imported, the produce in markets is shipped in weekly from the bush — the countryside — so it’s better quality, and cheaper.

Nortey also prefers shopping at markets because she can haggle the price down. She got a huge bag of tomatoes, which Moses originally priced at 12 Ghana cedis, for just 10 cedis (about $2.60.)

“You can negotiate with them; they’ll reduce the price for you, that’s why most of the time I come to the market to buy,” Nortey says.

Haggling is something that Ghanaians actually love to do. People expect it. So it’s a big part of Moses’ tomato selling strategy. “These ones I’ve packed here, I price it at 10 cedi. Maybe the customer comes and says: ‘I want a discount,’ so you let them buy it at nine or eight.” If she knows there’s a shortage of good tomatoes she jacks the price up to 14 or 15 cedi. "Or if the market’s dry, you’ll say ‘it’s 15, but give me 14.” So the price doesn’t stay in one place. There’s no one price, Moses says — she holds all these figures in her head.

Ghanaian women have found a way to thrive in this “informal economy” of trading, says George Owusu, a local economist whose work on market women was published by the Brookings Institution. In other research, he found that 60 percent of women in Ghana start their own businesses, compared with just 42 percent of men.

Owusu has a personal reason for the focus on these small-business owners: own mother was a market trader. “She would go to Accra, buy clothes and other things, and come back and sell,” he says. His father was retired, so his mother was the main breadwinner for the family of 12.

Troubled days for market women

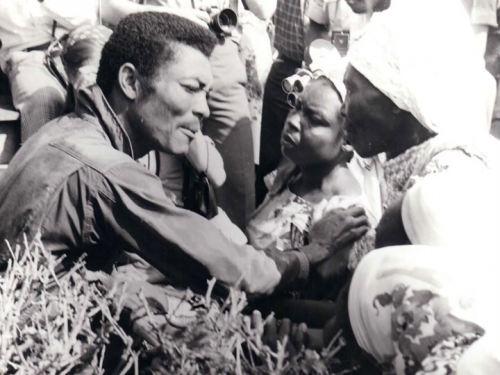

Owusu was about six when an Air Force lieutenant named Jerry Rawlings staged two successive coups d'etat and became Ghana’s military dictator. Owusu remembers the military curfew at 6pm and soldiers rolling through town, targeting everyone they considered a threat, including his own landlord.

“We were living in this apartment owned by a retired military officer, and this man was picked up. Apparently as very sympathetic to the regime which had been overthrown,” says Owusu. “And the military, at the time put this man through hell. He was stripped naked except with panties on, and he was paraded through the streets of the town.”

Owusu’s mother was also considered a threat too. “The military will come in and they will find somebody to blame,” he says. “And unfortunately, it looks like at the time, the easiest target they could pick were market women and women engaged in businesses.”

Market women were accused of driving up the price of everything in the markets. One politician said they were causing “moral decadence and economic degradation.” The army stormed the markets, searched the homes of traders and seized everything in sight. There were arrests and public floggings. Some paid with their lives.

“If you were a trader, it wasn’t safe for you to engage in any meaningful trading, because if you are caught, or you were seen, or you were reported to be overpricing your goods beyond what the soldiers want you to sell your goods, then you have a problem,” Owusu says. Traders faced a stark choice: Sell for less than your goods are worth (which will almost certainly put you out of business), or risk arrest and worse.

“To avoid all this, my mother stopped trading,” Owusu says. She shut her stall and smuggled some of her unsold stock to friends and family in other parts of the country. But that wasn’t enough. Most of her money was tied up in expensive bales of textiles, which she had to destroy. She cut up the textiles, so if the soldiers came knocking, they’d look used.

It was a decade before she could trade again. “The income from my mother was quite critical, and here is the case, my mother had to abandon her trading abilities because of what was happening at the time, and I can tell you, the family went through hell,” he says.

Stories like this are distressingly common. Rawlings, the dictator, continued to claim that market women caused Ghana’s economic crisis. But then, a decade after that, he said the real reason for the floggings was that some market women had been rude to his soldiers. Whatever the case, in 1979 soldiers went to the country's biggest market complex in the heart of Accra, planted explosives and destroyed all the businesses.

Markets restored

Ghana is no longer a military dictatorship. And today, 36 years on, the markets of Accra are thriving again. Nobody really talks about the bad old days here now. Most of the women affected, like Owusu’s mother, have retired or passed on. But market women are well aware of the economic power they have, and the risks they’re taking on by running these businesses. Now, though, the risks are mostly economic.

Moses keeps an eye on all sorts of economic factors that could affect prices: a good harvest, or bad weather, or wedding season. This is all crucial, because Moses is assuming a lot of risk: she buys three crates of tomatoes every week. If she miscalculates, she could end up with a bunch of rotting produce and no money.

“You might be able to get 30 Ghana cedi [of profit]. On some you’ll get 20 on it,” Moses says. “Sometimes you just make exactly what you bought the crate for, with no profit at all, so you’ve tired yourself out for nothing.” She balances out the risks by saving — even if it’s just one cedi (about 30 cents) — every day.

A guy at the market comes around, collects cash from her and holds it until the end of the month. The practice is an old one, and it’s called “susu.” It means that the money doesn’t get spent, and she doesn’t have to carry lots of cash around. This lump sum is the reward that keeps her going, it’s pushing the next generation of her family into the middle class. The other thing that keeps her going? Her customers.

“Always give the customer a little something extra so they’re happy and they keep coming to you,” Moses advises. “Be good to them, and the customers keep coming.” With that, she pours an extra bowl of tomatoes into her customer’s already bulging bag.