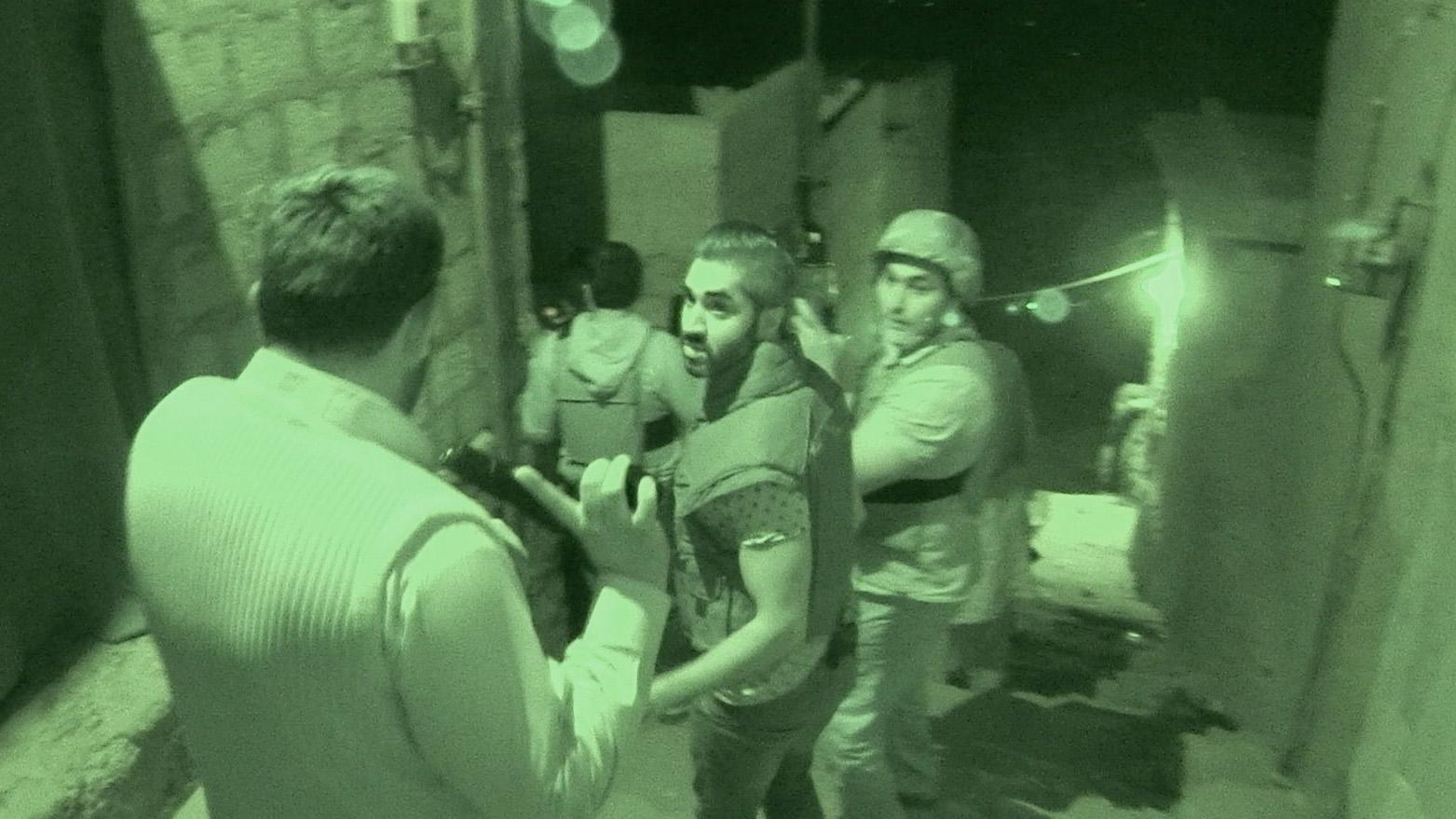

Police in Karachi prepare for a night raid on a suspected Taliban kidnapping cell with reporter Mobeen Azhar (centre). The Pakistani Taliban have 'top-sliced' organised crime gangs across the city.

Pakistanis have long been among the world's biggest victims of terrorism, with only Iraq and Afghanistan suffering more fatalities as a result of terror attacks in recent years. For more than a decade, the tribal belt in northern Pakistan has been the backdrop for the battle with the Taliban.

More recently the militants have moved into Pakistan's cities, with Karachi becoming a focal point.

I spent three weeks on the frontline embedded with Karachi police with a squad that has become known as the Taliban hunters.

At 1:15 a.m., my phone rings. It's Senior Superintendent Ijaz calling to let me know his team will be conducting an anti-Taliban raid later that night. "I have bulletproofs for you," he tells me. I've been watching Ijaz work for the past two weeks. He's in his 30s but the bags under his eyes suggest he's packed a lot into those years.

By 2:15 a.m., I'm picked up from my hotel by a cavalcade of police vehicles and taken to officer Ijaz's central Karachi compound. I arrive in time to hear the pre-raid briefing.

"I'm in the mood to take the suspects alive. Only fire your guns with express orders from me or the other senior officers," Ijaz instructs his squad of 24 Taliban hunters.

Tonight marks the culmination of four weeks of surveillance. The target is a cell of suspected Taliban members. The police have been tracking their phones. They have intelligence suggesting the group is planning a kidnap.

Karachi, Pakistan's biggest city, an international port with a population of 24 million people has now been in the Taliban's grip for more than two years. The city has become a cash cow for militants who have "top sliced" Karachi's gangs.

They make money from kidnap and extortion, with target killing and bombing their choice tools of terror. The latest available figures show 132 cases of kidnap were reported in Karachi in 2014, with the Taliban and affiliated groups being the primary suspects in almost all of these cases.

A cavalcade of five police vehicles sets off from the armoured compound. We travel north to the edge of the city. Ittehad town, a spiralling collection of pop-up slums, gullies and unregistered building has long been a no-go area for many Karachiites.

Shootout

The police don't come to this area without backup. We've come as far as we possibly can in police vehicles. The suspects' hideout is on a street so narrow we have to move forward on foot.

The light from central Karachi is miles behind us. The only sounds are our footsteps, whispering and dogs barking in the distance. With the hideout identified and surrounded, Ijaz gives the signal. Before his team can knock down the door, gunshots are fired from inside the building. "You are surrounded. Get down or we will shoot back."

A shootout plays out in front of my eyes and, after some tense moments, the two suspects are disarmed. Their weapons are seized and they are arrested.

Officer Ijaz explains: "Getting into the area is easy. Getting out is the difficult part." The members of the team leave the hideout and begin to walk back to the vehicles. The barking is now louder and the echo of metal bars being struck together ricochets through the air.

"The Taliban sound an alarm to let their supporters know the police are in the area. It's a call to arms. I have lost colleagues because of this."

We run back to the vehicles with the suspects handcuffed, leaving the Taliban's "alarm" in Ittehad town and returning to the relative safety of the police compound.

Just a few days earlier I had attended the funeral of Superintendent Mohammed Iqbal. He was killed in a Taliban attack outside his police station at the end of a 14-hour shift. He became the 164th officer to die on duty in a 12-month period. The Taliban hunters are in no way a specialist force. Many of them have no formal anti-terror training, and on some days even bulletproof vests and armored vehicles are difficult to come by.

Massacre

"We have been stretched to breaking point. It's easy to fight the Taliban in the north of Pakistan because there is a clear target," says officer Ijaz. "But in Karachi it's very difficult because you don't know who your enemy is. They hide out in the slums. We are in a real war."

His force is making some progress, on paper at least. The number of officers killed on duty is down from 156 in 2014 to 79 in November 2015. "The government anti-Taliban operation in Waziristan has been a great success. The Taliban are finally retreating," he tells me.

The military operation "Zarb e Azab" or "Sharp Strike", launched last summer, has been hailed as a success by Pakistani officials. But some fear the operation has simply driven militants from their Waziristan stronghold, further into Pakistan's urban centres. The Taliban struck a busy school in the city of Peshawar late last year, murdering 152 people, including 133 children. They claimed the attack was in response to the Zarb e Azab operation.

The massacre sparked unprecedented outrage in Pakistan, with peace rallies being held in every Pakistani town and city. The government lifted the moratorium on the death penalty, outraging human rights groups and doing nothing to lift the woefully low conviction rate.

Officer Ijaz tells me this is now the biggest hurdle in tackling violent extremism in Pakistan. "Testifying in court against the Taliban is a risk that many people are just not willing to take. It can often take 10 years or more for a case to go through the courts. Justice delayed can often be justice denied. Without changes in the system the battle with the Taliban can't truly be won."

At the time of writing, the suspects arrested on the night raid have been charged with conspiracy to kidnap and multiple counts of terrorism against the state. They are still awaiting trial.

A documentary version of this story is available to view online as PBS Frontline's The Taliban Hunters. Viewers in the UK can also view the BBC Panorama documentary version of The Taliban Hunters.