What to do when the airwaves and papers tell these women they’re inferior — or worse?

A worker arranges a copy of the Business Daily newspaper at a printing press plant on the outskirts of Nairobi.

A few weeks ago, Kenya’s most popular morning talk show host, a guy called Maina Kageni, asked his listeners why women “push” men into relationships. He was offered a slew of sexist responses — sexism is basically Maina’s bread and butter — but one seemed to surprise even him.

“We have domesticated human pets,” the caller said, referring to women, “and we have domesticated human pests.”

It’s a logic that suggests women are dependent, creatures to be tolerated at best. It’s not an idea that allows them to be much else — say, for example, human.

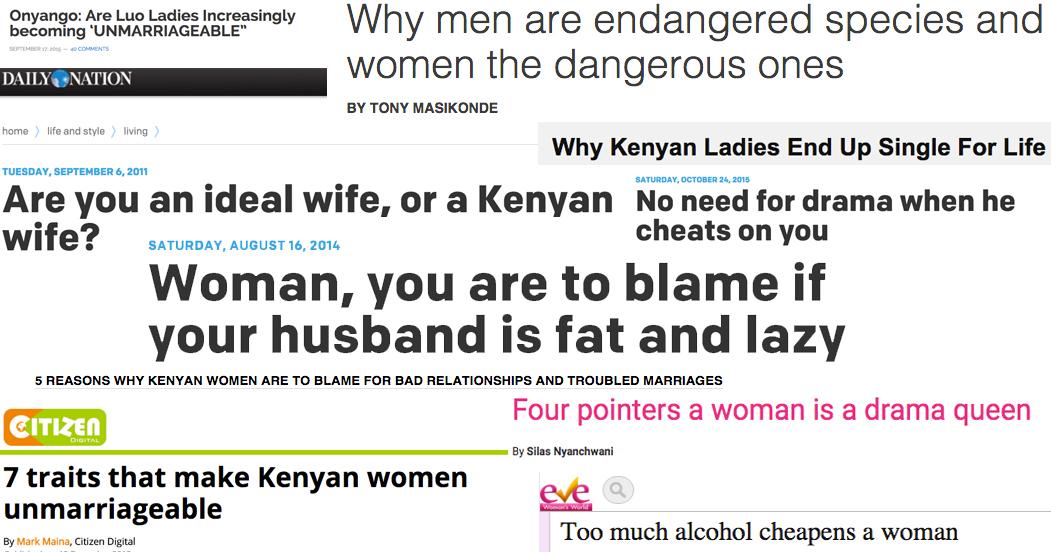

Maina didn’t respond to my requests for an interview, and to be fair, this problem doesn’t begin or end with him: Sexism is rampant in Kenya’s media. A Saturday column called City Girl, written by a woman for the country’s most-read newspaper, the Nation, regularly invokes patriarchal tropes:

“No need for drama when he cheats on you,” was the title of one column. Note the inevitability of infidelity, as if women would be delusional for demanding that their partners don’t betray them.

“The ideal wife vs. the Kenyan wife,” another was called, clearly implying a woman can’t be both.

A recent political cartoon lampooning Anne Waiguru, a minister whose offices have been embroiled in a corruption scandal, depicted her as a dominatrix. Kenya has no shortage of corruption scandals, but this was the first cartoon to sexualize the civil servant at the center of one.

And sometimes, you can open the paper and find yourself defined by it.

That’s what happened to Nanjala Nyabola. The well-known Kenyan writer and analyst spent months organizing a weeklong cultural festival in Nairobi. It was a hugely successful event with performances and panels and a cultural fashion show. But when the Daily Nation, Kenya’s biggest and best paper, wrote it up, they turned her into a man.

“I open the paper, and in the entire article, I am referred to as 'Mr. Nanjala.' Like, consistently,” she said. “And I should say at this point, it is definitively a girl’s name.” The paper’s mistake “is like saying Mr. Julie or Mr. Barbara,” she says.

She asked the article’s reporter — whom she’d met several times, and who was therefore quite clear on her gender — what happened. “And he said, ‘I’m really sorry, the copy editor changed all the Misses to Misters.’”

It’s an example that shows just how deep sexism is embedded. And this is not a situation without consequences, even bigger than the ones Nyabola felt.

“You do find a lot of women starting to shy away from public positions, whether in corporate, whether in politics, anything that requires them to 'have a thick skin,' because it’s just too vicious,” says Ory Okolloh.

Okolloh is no stranger to standing out. She’s been a fixture in Kenyan civil society since she co-founded Ushahidi, a mapping software that helped expose the country’s post-election violence in 2007 and early 2008.

She’s afraid that the relentless sexism in public space drives people away from being ambitious, whether that ambition is business, politics, or social change. And as the mother of three daughters, she’s afraid of how it affects the country’s youth.

“If they didn’t have any influence other than the newspapers, from a media consumption point of view, I worry,” Okolloh says.

Newspaper editor Dennis Galava sees it differently. He calls the kind of stories that worry Okolloh “uncomfortable truths,” and he thinks they’re important to get out in the open, since these are notions already expressed commonly in private spaces.

Galava says his paper strives not to generalize about any group of people, and that it regularly runs stories that feature empowered women, as well. But there’s another mission too, he says, to keep women vigilant.

“Don’t make them zombies, make them also to be awake to the realities around them,” he said.

If sexism is fair game, are there any limits? Has anything ever gone too far?

Once, Galava said. Only once.

It was an article from two years ago, and it was the first column published in a special section called “I Am Woman.” The name of the article? “Why I want to be raped.”

“That was the only time when I’ve seen the corporate side of the nation being shaken by an article. Everybody ganged up and said, ‘That’s too bold. Stop it,’” Galava recalls.

"I Am Woman" was discontinued. You can’t even find it online now.

Click the cards below to find out what the Kenyan media has been sharing about women.