She’s one of the only women to pilot a ‘matatu,’ the minibus taxis that keep Nairobi moving

Margaret Wairimu is one of a handful of women matatu drivers in Kenya.

Before dawn breaks over East Africa, hundreds of thousands of Kenyans begin their daily commute into Kenya’s traffic-laden capital, Nairobi. Most get to work by packing themselves into garishly painted minibuses known as “matatus.”

Known for their dangerously aggressive drivers, matatus are not just a cheap and fast means of transportation — they are a way of life in Kenya. And they’re also a subculture that is almost completely owned and operated by men.

oembed://https%3A//www.youtube.com/watch%3Fv%3D7SXC-0fUhOw%26feature%3Dyoutu.be

Almost, that is. Because of Margaret Wairimu.

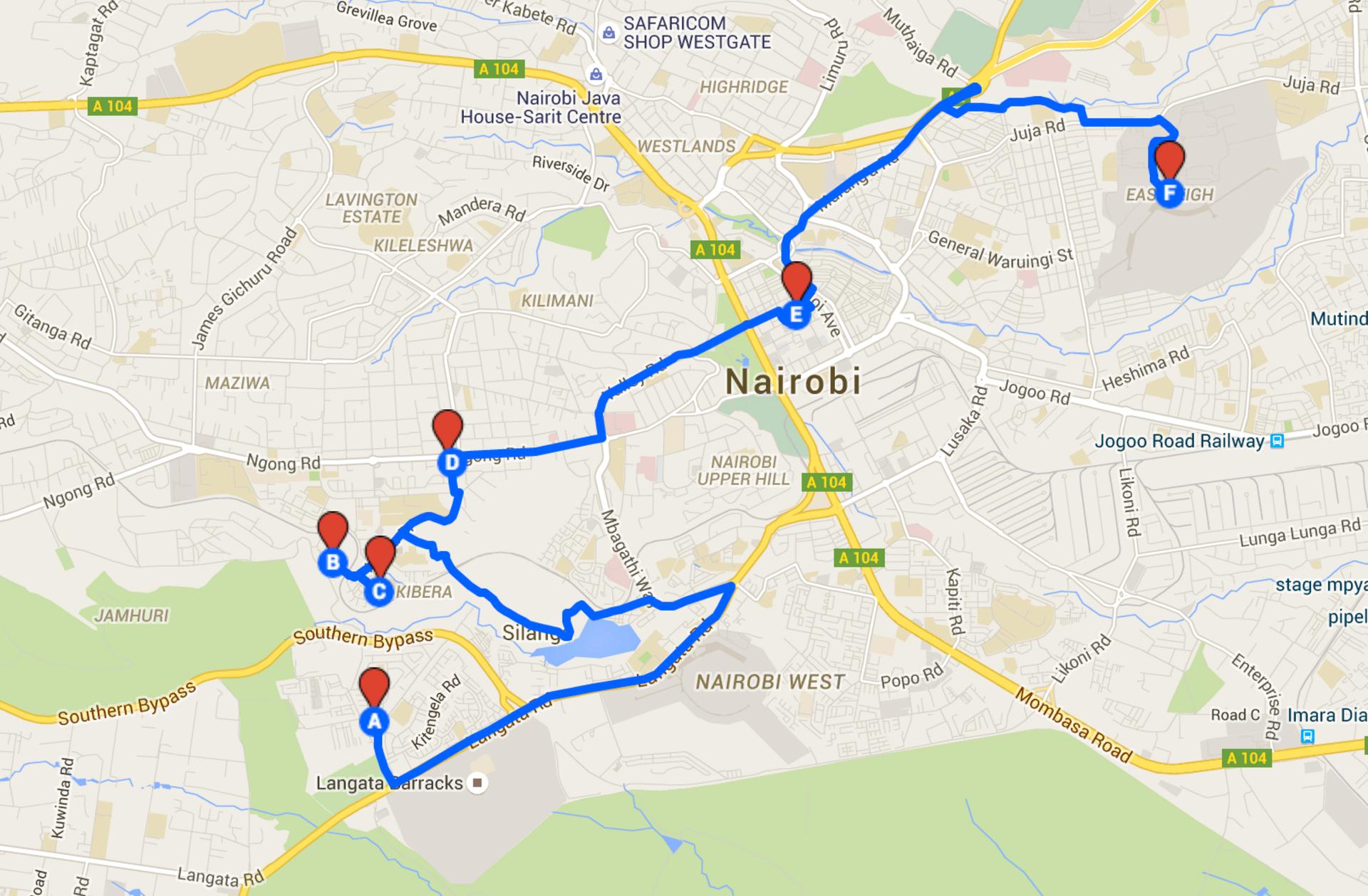

The rutted, crumbling roads of Nairobi are her office, an ever-shifting landscape of traffic, congestion and moving objects. It’s 8 a.m. — two hours into her morning shift — as she passes through the sprawling informal settlement of Kibera, the largest urban slum in Africa. Dozens of tiny shops crack open their doors as she drives by, the air filling with the smell of thick exhaust, roasted chicken and burning garbage.

Wearing the traditional matatu driver’s uniform — a navy-blue collared shirt, black vest and matching trousers — the 32-year-old mother looks like any bus driver in Kenya.

The only thing setting her apart from her male colleagues is her short bob haircut covered with streaks of blond highlights — a hint of femininity against a male-dominated backdrop of the East African matatu industry.

And that’s exactly how Wairimu likes it.

It’s clear from the start that Wairimu is a natural driver, weaving through the congested streets of downtown Nairobi and Kibera with ease.

“I’m the only one driving a small car [matatu] in Kibera,” she says while pressing the bus horn, which lets out a deep, undulating growl as it overtakes a slow car.

In fact, Wairimu is one of the only women in Kenya who owns and operates her own matatu bus. In Kenya, most women “are housewives,” Wairimu remarks with a laugh. “They stay in their house.”

Wairimu has been in the matatu business for 10 years and still drives the same streets she started on as a tough-as-nails young woman.

Forced to drop out of primary school after her father suddenly died, Wairimu, who only speaks a bit of English, was determined to find employment to help support her six siblings.

“I just woke up one day and went to one of the bus (stations) and asked to become a conductor. I was standing at that corner,” Wairimu says, pointing at a corner full of matatus and bustling men shouting in sheng, the Swahili slang dialect.

It took three or four attempts to convince the matatu owner to hire her, but eventually Wairimu got a job.

Initially employed as a matatu conductor — the person who convinces passengers to board their matatu using a series of persuasive yells and repetitive calls — Wairimu closely studied how other matatu drivers navigated some of the most treacherous traffic in the world.

Using that knowledge, she was able to sway her boss into allowing her to park his matatus after they retired for the day. And “slowly by slowly,” Wairimu says she learned how to drive.

“I only practiced on my own,” she says nonchalantly. “Then I did the driving exams and got my license.”

These days, Wairimu is no longer just a matatu employee; she’s her own boss. She and her husband, also a matatu driver, own two minibuses, which they operate every day of the year.

And like many Kenyan women, Wairimu wakes up early, works hard and sleeps little to keep her family financially afloat.

“I start at four in the morning,” she says. “Even when I’m not working, I wake up at 4 a.m. and end work at 1 p.m.,” she says. Then she starts her second shift, so to speak, caring for her children, keeping house and cooking. She usually gets to bed at midnight. “I don’t sleep.”

Even so, Wairimu lives and dies by the nine-mile circuit she drives several dozen times a day, earning between 20 and 50 shillings (about .19 and .48 cents) per passenger. That’s not nearly enough to provide for her 8-year-old son, she says.

“There are so many expenses, and the money that I make is not enough.”

Wairimu says she wants her son to stay in school, and ultimately choose a different career path than she did.

“He should try anything else, but not a matatu driver,” she says.

Still, Wairimu isn’t one to complain. The woman who once dreamed of being an airline pilot says she’s simply happy to have employment.

“I like my job because I don’t have another one,” she says. “I’ve never had another job — it’s always been matatus.”

Though Wairimu admits she does receive occasional flack for being a female matatu driver, she also says that ultimately, most men in the industry respect her grit and determination to make it in a man’s world.

“So many people say this work is for men, but what a man can do, a woman can do better,” she says, smiling.