Who’s afraid of Simone de Beauvoir? How a national exam had millions of Brazilians talking about gender.

Simone De Beauvoir, painted portrait.

At the end of October, 7 million young people had to sit and think about the persistence of violence against women in Brazil. This was the essay theme of the National High School Exam — a Brazilian standardized test that is mandatory to compete for a place in the country's public universities.

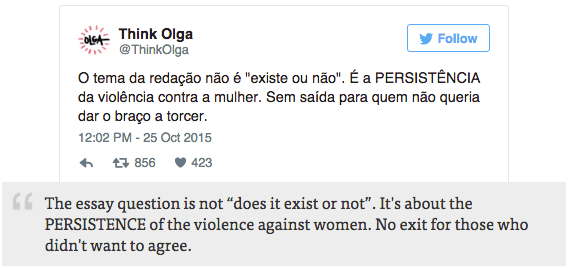

A question in the humanities test also included an excerpt from the French philosopher Simone De Beauvoir’s book, “The Second Sex,” and another one cited the queer and chicana feminist Gloria Anzaldúa.

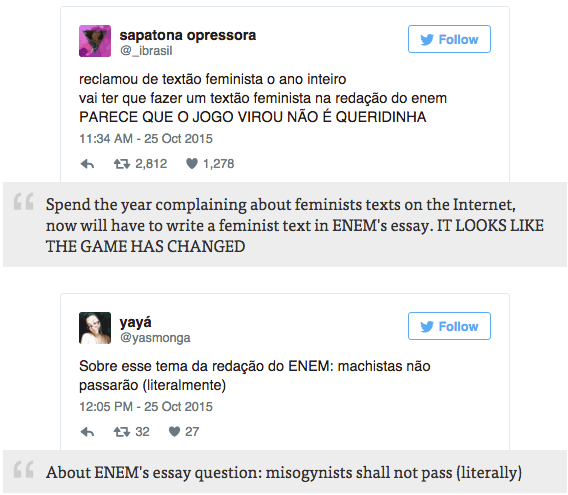

The Brazilian Internet exploded. Feminists took to Twitter and Facebook and celebrated the “most libertarian and feminist” version of the standardized test so far. It seemed that knowledge of feminist theories were extremely relevant for achieving a good mark on the essay, an important component of the overall grade. But what about the trolls who spent the year harassing feminists on the Internet?

The backlash begins

A photo of one of the test questions featuring the excerpt from Beauvoir circulated on social media. It read:

Of course, a feminist celebration online wouldn't see the end of the day without receiving major backlash. Many users criticized the so-called “government indoctrination” toward gender and sexuality.

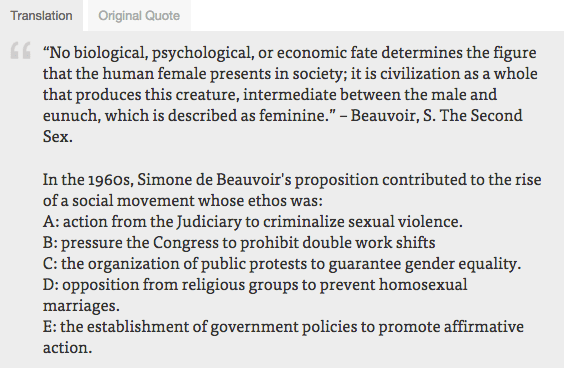

Among them were two of the most controversial congressmen in the country: Jair Bolsonaro, known for his unrestricted defense of Brazil's past military dictatorship, and Marco Feliciano, an evangelical pastor who once tried to legislate the “gay cure.”

Bolsonaro went so far as to say the alleged “indoctrination” was worse than corruption. He cited the governing Workers’ Party and republished the photo of the Beauvoir question:

BBC reported Beauvoir’s entry on Wikipedia went from 250 visits per day to 35,000. The entry also suffered several alterations in the days following the exam. Users added information claiming the philosopher had penned a “rape book”; fought for laws “prohibiting women to work outside their home”; cooperated with the Nazi occupation of France and campaigned to “legalize pedophilia.” The entry had its editing locked due to “excessive vandalism,” according to the Wikipedia page.

An anti-Beauvoir wave flooded the offline world as well. City counselors from Campinas, a city in the state of São Paulo, decide to submit to a vote a motion of repudiation against Beauvoir. For 22 minutes they went on a rant against “gender ideology,” same-sex marriage and menaces to the “traditional” family. One of them went as far as to state: “They want to force us to swallow this devious initiative … but the large majority favor nature’s law: a man is a man, a woman is a woman.” The motion was approved by the Chamber.

Gender-based violence in Brazil

Violence against women in Brazil is not a matter of left or right (or at least it shouldn’t be). All one needs to do is look at the alarming numbers of homicides and gender-based violence in the country. In 2014, Brazil had 47,646 rape cases registered, according to the Yearbook of Public Safety. That means — counting only reported cases — that every 11 minutes, a woman was attacked in the country.

Brazil also ranks 7th among 84 countries with the highest rates of femicides. The 2012 Violence Map revealed that between 1990 and 2010, 91,000 women were murdered in Brazil. Last March, President Dilma Rousseff signed a law including “femicide” as a heinous crime into the Brazilian Penal Code.

But is there hope? The last week of October saw some important developments in advancing the gender debate in Brazil.

Related: Brazil's shocking violence against women, in five charts

After some tweeted sexual comments about a 12-year-old girl participating in a Brazilian reality TV show, the hashtag #primeiroassedio (#firstharassment)engaged more than 82,000 women to share the first time they remembered being harassed.

The following week, #MulheresContraCunha (#WomenAgainstCunha) gathered thousands of women online and in the streets to protest a bill that requires rape victims to go through forensic examinations prior to accessing healthcare and could also criminalize the morning-after pill. Eduardo Cunha is the president of the Brazilain Chamber of Deputies and the main supporter of the bill.

In November, the campaign #AgoraEQueSaoElas (#NowIt'sGirls'Time) had several male columnists, writers and journalists opening space to female colleagues to write about gender issues.

This awakening is already being called #WomenSpring or #PrimaveraDasMulheres, with a new wave of protests scheduled for November. Times may be hard for those fighting for equality, but they also seem to be changing.

This story was cross-posted from Global Voices, a community of hundreds of bloggers worldwide.