Why did Sidney Denham die?

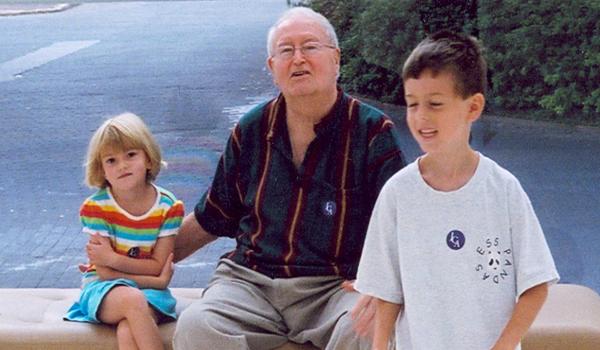

Sidney Denham and grandchildren, 2006

On July 14, 2011, a retired social worker named Sidney Denham was taken to an emergency room in Savannah, Georgia.

Weeks after undergoing prostate surgery, and days after resuming use of a relatively new blood thinner called Pradaxa, the 81-year-old widower was bleeding profusely from his urinary tract. He had lost so much blood that his pressure had plunged to about half the normal level and his body was in shock. In the intensive care unit, a medical team deployed treatment after treatment in a struggle to save him.

One of Denham’s daughters, Kay Denham, recalled the scene: “More blood than I think I've ever seen in my life … Millions of people in the room … They could not control the bleeding.”

A hospital record shows that Denham was given 12 units of red blood cells and another 12 of fresh-frozen plasma—almost two gallons. He was pumped with platelets and other blood products. He was put on dialysis to purge the Pradaxa from his system. Nothing worked.

Even as they replaced his blood, it was draining out of him.

“It was horrible,” said daughter Mary Denham, “that feeling of helplessness, for the people in the ER and for us. There was nothing they could do to stop the bleeding. My sister and I watched him bleed to death.”

Denham had been taking the anticoagulant Pradaxa to treat a condition called atrial fibrillation, in which irregular functioning of the heart can cause blood clots and strokes; the medicine is supposed to prevent the clots from forming. But, according to Denham’s “DEATH SUMMARY” from Memorial University Medical Center in Savannah, the FDA-approved drug contributed to his demise.

The patient, the document says, suffered an “uncontrollable hemorrhage from Pradaxa.”

The Food and Drug Administration is responsible for making sure medicines sold to the public are safe and effective. But how much comfort should medical consumers take from the words “FDA approved”?

In judgment call after judgment call involving the prescription blood thinner Pradaxa, which has been named as a suspect in thousands of patient deaths, the FDA took a lax or permissive approach, a Project On Government Oversight investigation has found.

The result was to accommodate a pharmaceutical company by easing a drug’s passage to market and then deflecting questions about its safety once the product had won approval. The issues ranged from what standards to demand from the manufacturer-sponsored clinical trial used to secure the drug’s approval to what warnings to give patients about potential hazards and what claims to allow in ads for the product.

POGO’s findings, based on interviews with key participants and researchers and upon thousands of pages of public records, many obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, call into question the reliability of a crucial regulatory system.

Read the full investigation of FDA approval procedures and Pradaxa at the Project On Government Oversight. UPDATE: On Oct. 20, the FDA approved an antidote for Pradaxa. More details here.

This article was written by David Hilzenrath. It was based on reporting by John Crewdson, Hilzenrath, and Michael Smallberg; it was reported principally by Crewdson. Lydia Dennett provided fact-checking and other editorial support. Editing by Danni Downing. Web design, graphics, and production by Leslie Garvey.