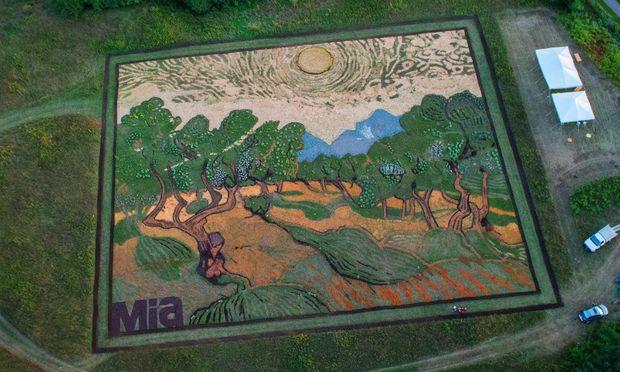

The living Van Gogh reproduction in Minnesota.

The Minneapolis Institute of Art has been throwing a year-long party for its 100th birthday, and the guest list has been a bit of a cultural catch-all. Devo’s Mark Mothersbaugh stopped by, only to be followed up by da Vinci and his mirrored codex. Heck, it's a party, why not ship in a fresh crate of Delacroix? But wait — what about the grand gesture to round it out?

How about a 1.2-acre rendition of a Vincent van Gogh painting, composed with items you could buy at Home Depot?

Van Gogh’s original piece, Olive Trees with Yellow Sky and Sun, measures about two feet by three feet and hangs on a wall in the MIA. The new rendition, by land artist Stan Herd, covers 1.2 acres, or 7,230 Olive Trees. It’s so big that you’d have to fly a plane over it to appreciate it — say, from the nearby Minneapolis-St. Paul Airport.

As a land artist, Herd knows that most of his work is just too big to fit inside a traditional museum, and that's OK by him.

“I’m a Kansan, and I make art on a frickin’ tractor. Do I really want the avant garde en Paris to see it?” Even if a major museum could secure zoning rights, representational art like the kind Herd makes is of out of fashion in the art world. Surprisingly, the person who might appreciate Herd’s work the most is van Gogh himself.

Van Gogh painted Olive Trees during his stay in the French region of Saint-Rémy. He’d come there to stay at the infirmary and to get away from the city. He was annoyed by his contemporary Paul Gauguin's loose allusions to nature, and he was assiduously attempting to represent the countryside around him. Between sessions in the field, van Gogh would write to his brother, Theo:

“I’ve been messing about in the groves morning and evening on these bright and cold days, but in very beautiful, clear sunshine. … In the face of the difficulties of the weather, of changing effects, a heap of ideas like this finds itself reduced to being impracticable, and I end up resigning myself by saying, it’s experience and each day’s little bit of work alone that in the long run matures and enables one to do things that are more complete or more right.”

Van Gogh wanted to push himself to render what he saw in the fields. Herd, like a looking-glass van Gogh, uses the land to represent the painting — on a different continent, in a different climate. What would van Gogh, a painter so dedicated to representing the land, think of having the land represent him?

Van Gogh struggled with the resistant materials of paint and canvas. Herd had to deal with the weather.

“I would get up in the middle of the night in the hotel room and watch AccuWeather and watch storms come towards the field that desperately needed rain," he says. "One week four separate rains came. One of them was 800 miles wide, coming from the neighboring state, spreading across the state, great big beautiful red and yellow, which is at the center of the major storms. And it came up to Minneapolis, came up within five miles of my field, and dissipated.”

Herd's slice of Saint-Rémy won't last forever. It will fade over time. Surprisingly, so will van Gogh’s. That's because he painted with pigments now known to be “fugitive,” like a very slowly disappearing ink. The chrome yellows and scarlets scattered throughout the painting's sky will, in time, wilt like the marigolds in Herd’s field.

Everything in nature is ephemeral — van Gogh would probably like that.