They know: Hiroshima survivors help those in Fukushima overcome fear, discrimination

Radiation hotspot in Kashiwa, February 2012

Hiroshima and Nagasaki survivors know their experience was unique. Their ability to convey its magnitude compounds their trauma. Many say this.

Living through the atomic bomb may be best thought of not as a single experience, but a series of experiences: the blast itself, flattening buildings for miles around; the radiation exposure; the anticipation of radiation sickness; and the discrimination from others who kept their distance fearing contagion.

For those affected by the Fukushima nuclear accident in 2011, there are some echoes. There are major differences, too: the massive exposure to radiation in Hiroshima was intentional and far deadlier than the Fukushima accident. But what’s striking is how similar the public reaction has been to victims.

Many Japanese express similar views. Fukushima’s radiation has not been deadly, but nearly 500,000 people were evacuated from their homes. Health officials say they may be prone to certain cancers in the future, but no one knows for sure. Some of those affected display symptoms of extreme stress.

Discrimination

In Hiroshima, Kano’s grandparents decided to get married in the knowledge that they were both A-bomb survivors, or hibakusha as they are called in Japan. Many survivors chose this route because it was the only option if they wanted to have a family.

Naono worries that that they may be happening all over again with Fukushima.

“I know that some young students in Fukushima worry, ‘Oh am I able to get married? Or am I going be able to have a child?’” she says. “There is certainly fear among the survivors of Fukushima.”

On top of the fear, there’s outright discrimination. “I was shocked by hearing stories of those evacuated from Fukushima are rejected at some hotels because they are thought of as infectious or something,” says Naono.

Hotels, schools, hospitals — anywhere where displaced Fukushima residents have gone, they’ve sometimes faced ignorance and rejection. The city of Tsukuba in Ibaraki prefecture even required people who were seeking to relocate there to prove that they weren’t carrying traces of radiation. The has now scrapped that rule.

“It’s kind of sad to see those phenomena in Japan,” says Naono. “I feel like Japanese society hasn’t learned anything from Hiroshima.”

“Just like Hiroshima’s survivors, people from Fukushima need to speak their mind,” says Nanakida. “Before it’s too late, and they bottle everything up.”

Yakult Ladies

For that, she says, they need to be around people with similar experiences. Which is why Nanakida turned to an unlikely source for her Fukushima research: a health drink company.

In Fukushima, the probiotic drink Yakult is delivered to people’s homes by so-called “Yakult ladies.”

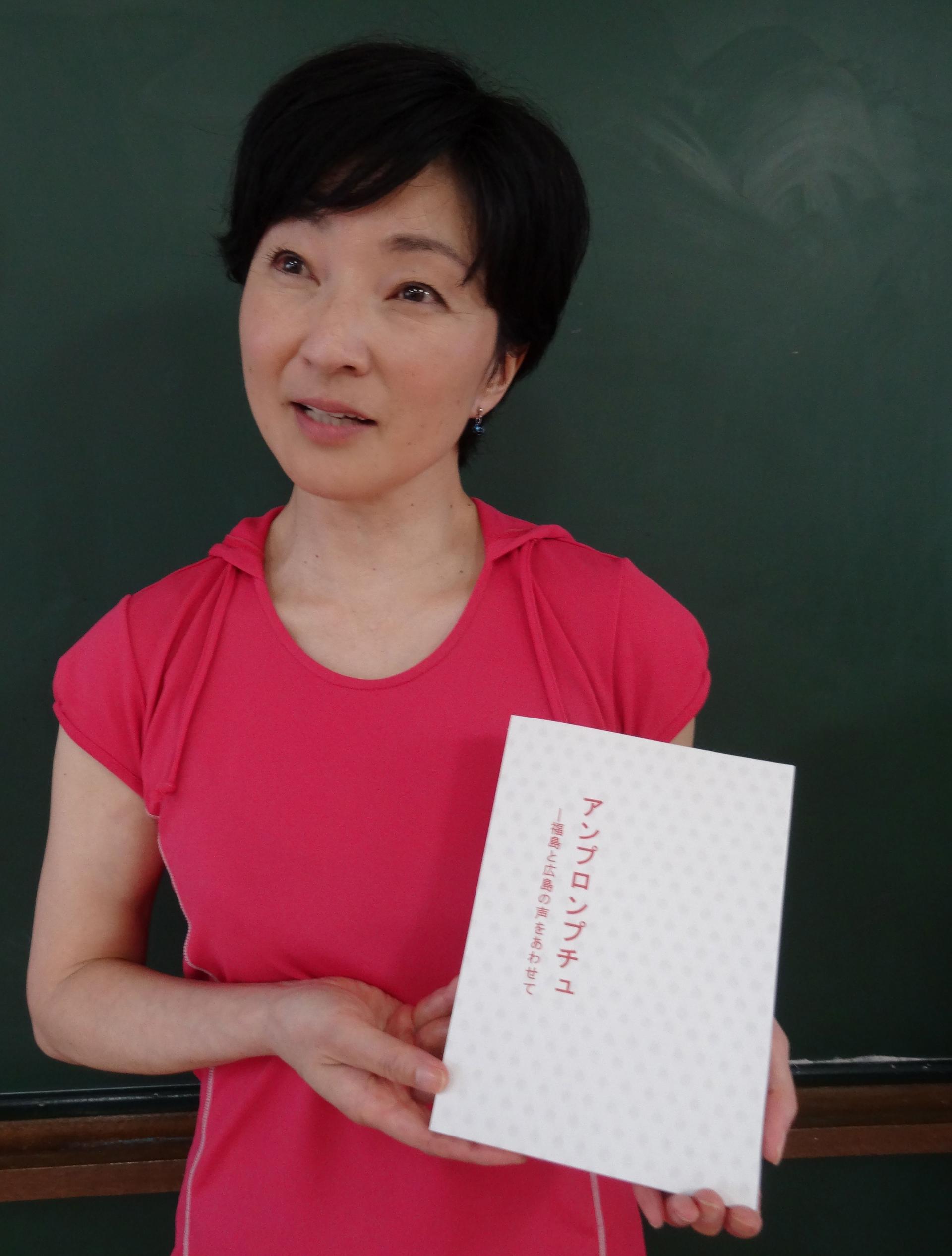

With help from the Yakult ladies, who are trusted by the locals, Nanakida got Fukushima residents to submit poems and short essays for her book. Then, she asked Hiroshima survivors and their relatives to do the same thing. The result is an outpouring of pain and fear.

“We were evacuated to another prefecture,” wrote one Fukushima mother. “My child was nicknamed ‘radiation.’

“After we returned to Fukushima, we were told, ‘You ran away.’”

This mother told Nanakida that the invisibility of radiation makes her feel like she is “walking in fog.”

An entry by a Hiroshima man is addressed to his parents who survived the blast but are now dead. He regrets not having asked them more questions, especially how it felt to give birth to him “in the midst of tragedy,” as he puts it. “I didn’t push them to talk,” he writes. “Now it is too late.”

Nanakida’s book addresses that very regret. The act of writing these things, she says, is a release. Reading them, too.

Possible radiation exposure can cause both visible and invisible trauma, Nanakida says. Her concern is the invisible, the mental trauma. She leaves it to others will have to determine the extent of the visible, the physical. Of course, our incomplete knowledge of radiation’s effect on the body adds to the mental anguish — and feeds the discrimination.

That said, Fukushima residents can look to see how Hiroshima’s survivors have fared, both mentally and physically.

One person who can easily make the Hiroshima-Fukushima connection is Aya Kano, the woman whose uncle is a Fukushima evacuee and grandmother a Hiroshima survivor. There were suspicions that her family, like other survivor families, somehow “carried” radiation, even down the generations. But today the family is fine — which is proof of something.

“My grandma is OK. My father is OK — still alive and fine,” she says. “So the people in Fukushima should be OK. I believe that.”

Words of hope from someone whose family has lived through three generations in the shadow of the atomic bomb.

This is the final part in a series of reports supported by the United States-Japan Foundation.