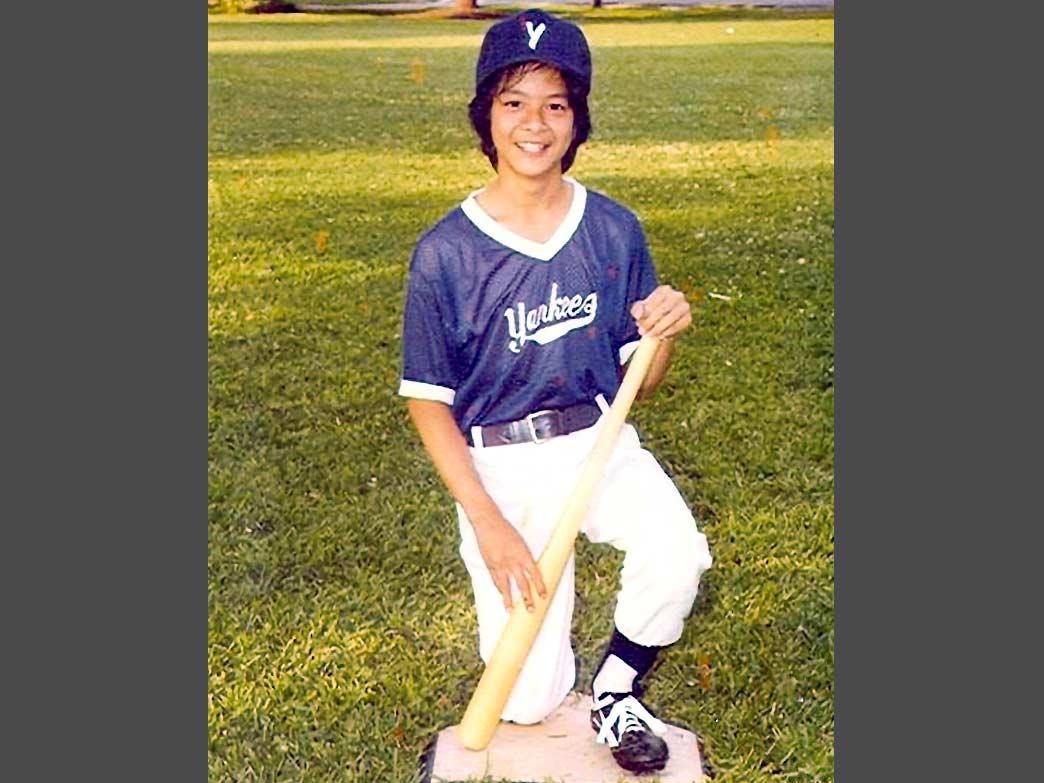

Joshua Nguyen arrives to Boise, Idaho, in 1975. He and his family fled Saigon, the South Vietnamese capital at the time, when North Vietnamese military forces captured the city.

First stop: Guam.

That’s what Joshua Nguyen remembers, after he and his family fled Vietnam in 1975, when North Vietnamese forces captured Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam. Like many others, they left on crammed ships for Guam, where the US government had established a base where the refugees would wait until they were processed for resettlement elsewhere.

Nguyen was 10. When he got off the boat, he realized someone was missing: His dad.

“He still was not with us,” Nguyen recalls.

During that chaotic moment when they were fleeing Saigon, Nguyen’s dad went back into the city to gather more relatives so they could leave by boat too. He didn’t make it back to the city’s port in time to join his own family, and eventually boarded a boat later.

But in the days in between, Nguyen waited for his dad to arrive on Guam. Every day, schoolbuses filled with new arrivals would pull up into the refugee camp. “I would jump on every bus that came through there, and I’d say, “Bah!” real loud, hoping he’d recognize my voice and respond.” (Bah means dad in Vietnamese.)

“And every day, there was no answer,” Nguyen says. “But, you know, I never gave up. I don’t know how many buses I climbed on. Then one day, I jumped on the bus, did the same thing, and I heard his voice.”

“He was crying … so I took his hand and took him back to where we were staying. I said, ‘Mom, look, hey, dad is right here!’” His mom burst into tears. Nguyen says he didn’t quite absorb the stress his mom had felt until then. “I was like, ‘What’s going on? Why are you all crying?’”

Then, it was off to Boise, Idaho. They arrived on July 3.

“And the next day there was this big celebration,” Nguyen remembers. “And I’m thinking, ‘Hey, wow, look at that, fireworks for us. They really want us here.” And I didn’t know until later, when somebody told me that was Fourth of July and they did that every year. So it kind of busted my bubble.”

But then another holiday came around.

“Later that year, we were at the church family’s home, and they told us, ‘Okay! Let’s get ready! You’re gonna dress up.’ And I was like, ‘I don’t have a costume.’ So they grabbed me a sheet, threw it over my head,” he says.

They told him to go and knock on doors and say “trick or treat” and hold out a bag for candy.

“I was like, wow, how strange is this. They have no idea who I am now with the sheet over my head, but yet they give me candy. This is great, so I spent all night, up until midnight, ringing on everybody’s doors, getting all these candies. I was sick the next day,” Nguyen says.

But getting real footing in the United States was tough.

“None of us spoke English when we got here,” Nguyen said. “I picked up most of my English from watching ‘Sesame Street’ ‘Electric Avenue’ and cartoons and 'Scooby Doo.’ So we kept to ourselves, and the refugees kept to themselves.”

Today, Nguyen is 49, lives in Houston, and says he wants his grown daughters to know this about that time. “That I came a long way to be their father, that they should not take anything for granted,” he says. “I thank god every day of my life and this experience reinforced that, that we’re all here for a reason.”