As Baltimore burns, community leaders condemn violence but urge reform

Baltimore city firefighters walk past a West Baltimore residence that was set ablaze after the funeral of Freddie Gray on April 28, 2015.

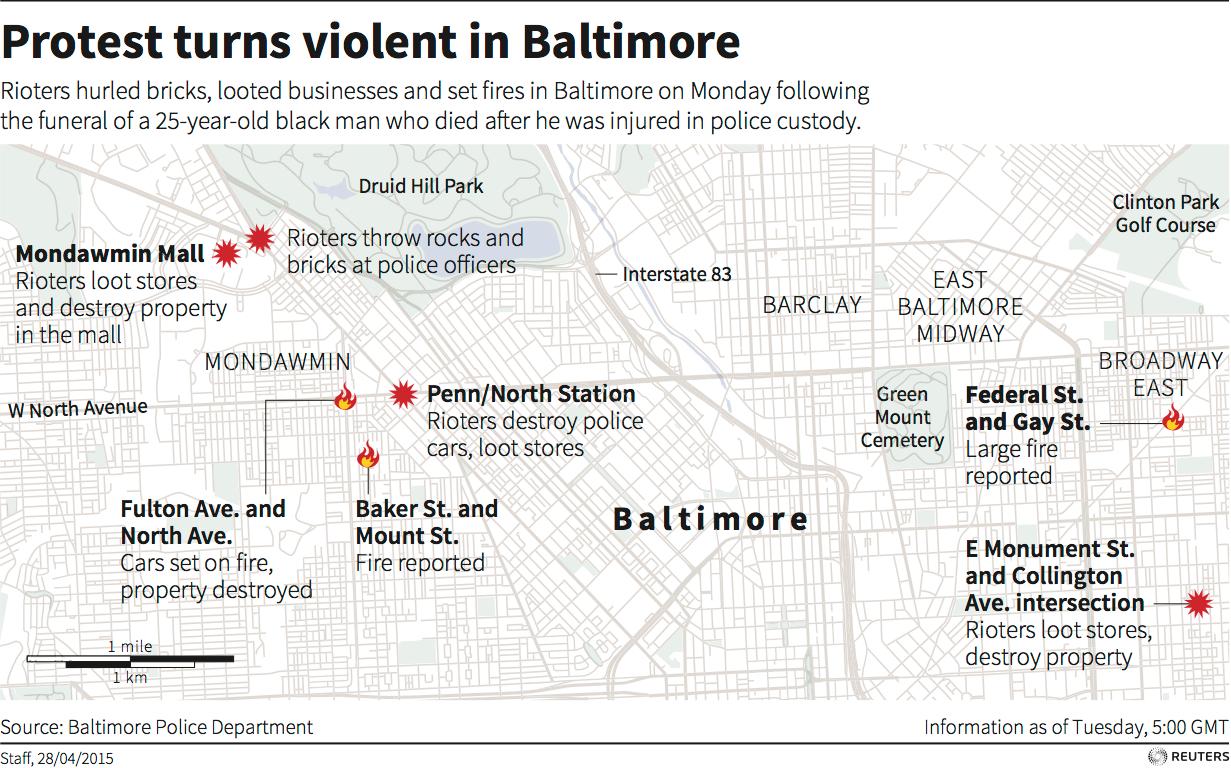

Rioting and looting engulfed the west side Baltimore on Monday following a funeral service for Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old African American man who died after suffering a spinal cord injury when he was taken into police custody earlier this month.

Hundreds of people turned out for protests over Gray's death, burning buildings and injuring at least 15 police officers — six seriously — by throwing bottles, rocks and bricks. It's not known how many protesters were injured.

As violence and destruction shook the city, Maryland Governor Larry Hogan signed an executive order declaring a state of emergency in Baltimore and activated the National Guard to address the growing unrest.

“Too many people have spent generations building up this city for it to be destroyed by thugs,” said Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake during a press conference. “I’m at a loss for words. It is idiotic to think that by destroying your city that you’re going to make life better for anybody.” The Gray family also condemned the violence, saying they were "appalled" by the Monday riots.

“Baltimore has been a divided city for a long time,” Miles says. “It’s a tale of two cities: A downtown that has been completely redeveloped and uptown communities that have been neglected for years. That’s what you’re seeing right now, a spillover of really 40 years of benign neglect; of young people who feel they no longer have a stake in the city’s future."

According to the US Census Bureau, nearly a quarter of the majority-black city lives below the poverty line. In Freddie Gray's West Baltimore neighborhood, unemployment stands at over 50 percent, as pointed out by US Rep. Keith Ellison on Tuesday.

“There’s a disconnect between older people in our community with the younger people,” Miles says. “It’s my understanding that the genesis of [the violence] came from social media and young people wanting to act out and others getting caught up in the frenzy. The frenzy both expressed anger and frustration.”

Though the city faces large challenges ahead, Miles says that there is no single answer to the city's problems.

“All of us have to take some responsibility for where we are,” he says. “It’s a corporate community that has not been engaged enough throughout the city, a political leadership that has often lacked vision and an unwillingness to listen, and even a faith community that sometimes loses connections with the people.”

In the meantime, the city is gearing up for more potential violence. Mayor Rawlings-Blake has imposed a weeklong 10 pm-to-5 am curfew starting on Tuesday, while city officials closed schools and the Baltimore Orioles postponed their games Monday and Tuesday. The Maryland State Police said they would ask for 5,000 law enforcement officials from the mid-Atlantic region to help quell the violence.

While Miles does praise the members of the Baltimore police and fire departments, he says that the entire community of Baltimore, including the police department, must step up to heal these wounds.

“I feel that the city is making some effort now to come together beyond the boundaries of neighborhoods,” he says. “But [divisions lie] not so much in neighborhoods as it is the division by class. There’s policing being done one way in the white community and another way particularly in the African-American community. I think that’s where the disparity comes in — there’s different styles of policing depending on where the police operate.”

This story is based on an interview from PRI's The Takeaway, a public radio program that invites you to be part of the American conversation.