Gian Dirik stands atop a barricade at a military base near the border of Syria and Kurdistan. The YPJ (pronounced "Yuh-Pah-Jhay") is an all-volunteer women's vigilante military unit formed in 2011 by the Kurdish citizens of Rojava, a province of Kurdish citizens in Syria, with the mission of protecting the citizens of the region.

Back in April, photojournalist Erin Trieb talked with us about her time photographing the YPJ, an all-volunteer women's military unit who have taken up arms to defend Kurdish citizens from ISIS in Syria. For our weeklong series called Teach Her, we're looking at women in STEM, sports education, sex education, arts education and women in the military. Here's a repost of a Q&A we did with Erin Trieb, asking her to tell us more about the YPJ women fighters and what it was like spending time with them.

Anne Bailey: Most of us know about the war in Syria but have never heard of the YPJ. Who are they and what are they trying to achieve?

Erin Trieb: The YPJ (pronounced "Yuh-Pah-Jhay") in Kurdish, translates to “Women's Protection Unit.” They are a female military faction, which sprang up in 2011 out of the larger YPG military, their male counterpart. Their goal initially was to defend the Kurdish population of Syria and all innocent civilians against the deadly attacks led by Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and to further the greater Kurdish resistance movement. However, they are now mainly fighting ISIS, who have repeatedly attacked Kurdish areas of Syria over the past two years. About 8,000 women from all over Syria, Iraq, Iran, Turkey and elsewhere have volunteered to join the YPJ, and their numbers continue to grow.

AB: What drew you to photograph these women and how were you received as an outsider with a camera?

ET: I spent four years off and on documenting US infantry soldiers fighting in Afghanistan and returning home to military posts stateside, so I’ve always been drawn to soldiers, their way of life, their discipline, and the psychology behind why they fight. When I found out about the YPJ, feeling compelled to observe and photograph them for me was instant. I think one of the most fascinating features of this particular military group is that they are unpaid volunteers. They aren’t drafted; they want to be there. And they are totally consumed with the ideology of defending their people and defeating ISIS, or anyone who opposes their freedom. They have complete tunnel vision and are totally disciplined physically, mentally, and emotionally. Seeing that makes them easy to respect, but I also want to understand what makes them tick and what fuels their commitment.

The YPJ are socialists. Like any guerrilla or freedom fighter group, they are suspicious of western media. And why shouldn’t they be? I had to earn their trust. Many high-ranking officials and generals would ask me, “Why does American media and government think we are terrorists?” I had to explain to them that most of the American public hadn’t even heard of them. This was a difficult concept for them, I think, because in northeastern Syria they are quite famous as the current ruling power. The fact that most Americans haven’t heard of them is equivalent to them not knowing about the US Marines in the battle of Fallujah, Iraq — which, sadly, I think many Americans also don’t know about.

However, when I first got to Syria in August 2014, I was welcomed with open arms by the women soldiers. It was a very special time for the YPJ then — they had recently begun fighting ISIS in places like Raabia, Iraq, and near Mount Sinjar and were starting to realize their integral role in the conflict. They told me I was one of the first western, American photographers to photograph them. However, now there are a ton of journalists they allow in, so it’s become sort of passé.

AB: What surprised you the most during your time with the YPJ?

ET: I was very surprised by how much they could do with how little they had. They told me that they didn’t have any international aid coming in regularly, aside from a few airdrops here and there in areas of heavy fighting. They operate mainly on donations from community members. They ate bread, watermelon, canned tuna and tea for breakfast. I lost weight when I was with them because there wasn’t a lot of food to go around. People from nearby villages would bring them blocks of ice to keep their water cold in 115 degree temperatures. They slept outside bombed-out buildings, their rifles beside them in case of an attack at night.

I remember one soldier, Narlene, created a phone charger out of what looked like a bunch of tangled wires and a couple of Duracell batteries duct taped together. They are incredibly resourceful, and they share everything. But beyond material supplies and the conditions they lived in, they were willing to die for their philosophy. There was no concept of “I” or “me” — they trade their individual identities for the larger collective identity of the group. A PKK fighter on Mount Sinjar once told me, “What is it to die? We are not afraid to die. So what? You take one bullet. Then it’s over; you’re dead. Everyone dies. For us, it will just come sooner and it will come because we were fighting for something we believe in.” It was remarkable to see girls as young as 18 deciding that this is what they would live and die for.

AB: In one of your photos, a group of women is carrying the coffin of a fellow fighter. It's a grim reminder that these women are truly on the front lines of this conflict. What differences, if any, did you see in the way these women approach war than male soldiers you've photographed in Syria or elsewhere?

ET: In the US military, women play crucial roles; however, they are still not allowed to fight in the infantry. I’ve been told a variety of reasons for this — that the men can’t emotionally handle seeing a female soldier get injured in the field, that women can’t fight because they aren’t as physically strong as men, that it could cause conflicts if men and women are mixed in the theater of war. If this were true, I imagine it would also play out for Syrian Kurds since gender roles are defined and are strictly abided by in Kurdish culture. For example, in Kurdish culture women aren’t allowed to date. Some women aren’t allowed to play sports outside, or have one-on-one coffee meetings with a male friend. Or it’s an embarrassment to your family if you aren’t married by the time you're 30.

However, the YPG and YPJ are changing the game. They are challenging cultural barriers, traditions and stereotypes of gender roles for Kurds. And somehow the Kurds are embracing it. YPJ soldiers will not marry or have kids. They sleep in the dirt, operate heavy weapons, fight alongside men, and kill ISIS militants — and they’ve earned the respect of many Syrian Kurds.

AB: You mentioned when we talked the other day that you've felt more inspired to document women's issues since you hit your 30s. Why do you think that is?

ET: I grew up a tomboy — climbing trees, playing in the dirt, racing neighborhood boys on my bike. To me, boys always seemed tougher, less high-maintenance, and more involved in the activities I enjoyed, like sports and playing outdoors. It wasn’t until my mid-20’s that I discovered strong female role models that I could look up to. And for some reason when I hit 30, I realized that not only did I want to cover more issues focused on women, but this coverage was absolutely necessary. It is mind-boggling to me that in 2015 femicide, rape and gender-based violence are still rampant in various parts of the world.

I think the 21st century is a very exciting time for women. More than ever, we are being empowered, breaking gender biases, and assuming leadership roles all over the world. But this also creates a contrast with the world’s darker corners where this is not yet happening. As a woman journalist, I can connect with other women and cover topics that often can not be photographed by my male colleagues. This inspires me to focus more on female-focused issues, and it also feels like a newfound responsibility.

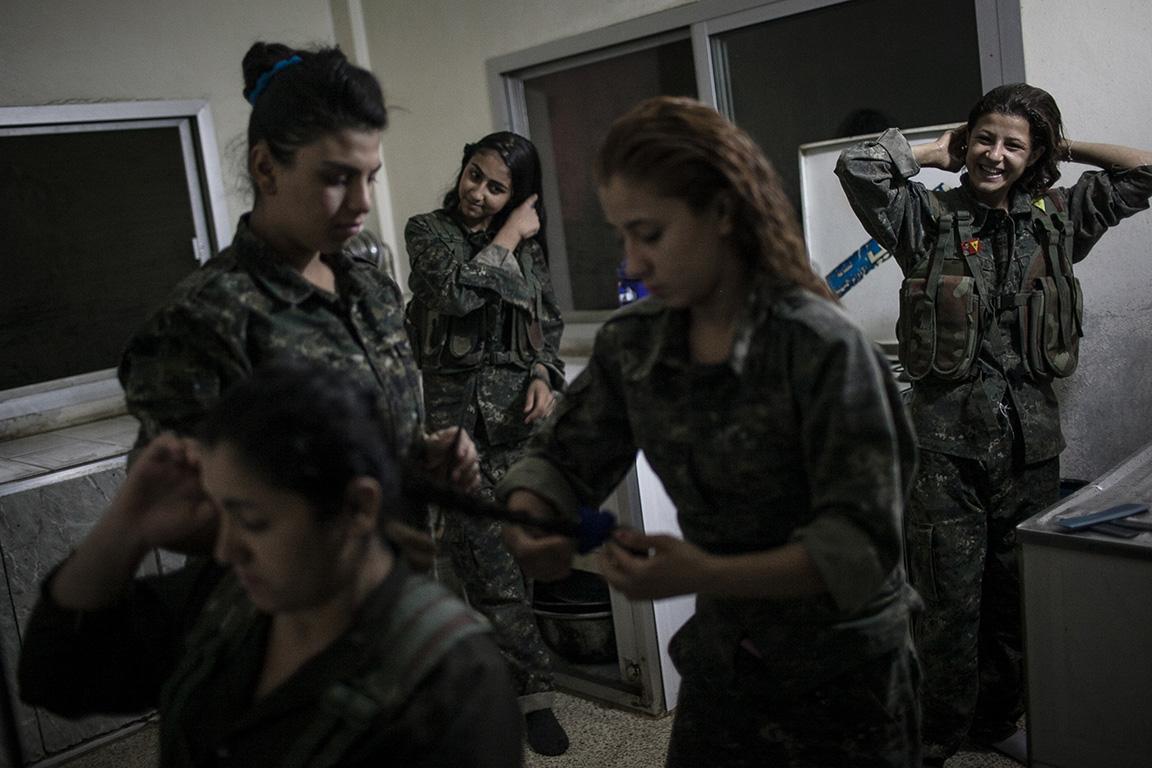

AB: I love the photo of the women and girls all fixing their hair. It's such a normal, everyday moment in the completely abnormal state of war. Did you see that dichotomy play out a lot during your time with the YPJ?

ET: There’s a saying among American soldiers that war is 90 percent boredom and 10 percent pure adrenaline. Most people don’t realize that there is so much downtime in war. In fact, downtime was only what I was able to photograph with the YPJ because their leadership forbade me to photograph them fighting because they thought it was too dangerous for a foreigner. The downtime moments juxtaposed with periods of intense fighting is what makes being in the theater of war such a bizarre experience. For example, I photographed some YPJ soldiers fixing a high-powered DsKH Russian anti-aircraft weapon that they used to shoot at ISIS militants, while 30 feet away a group of YPJ and YPG soldiers were laughing and goofing around playing a game of kickball.

AB: You took these photos last fall. Have you been able to follow up with the women and girls in the photos to see where they are now? Have they made any gains? Any plans to spend more time with them?

ET: I began photographing the YPJ and YPG in August 2014. In April of this year I went back to Syria to track down the same soldiers that I photographed last summer. The small group I initially spent time with there has since split up, and they are now spread out all over Syria. I did hear updates, however — that one soldier had fought bravely in Kobane and was well, that another was at a training school in the mountains, that another had been injured but was healing. Two of the soldiers I photographed last fall were killed in action. It’s always hard to lose someone you’ve photographed. That’s why journalists typically say “don’t get too personal.” But I'm human and sensitive and I like people, so getting somewhat personal for me is natural, and it makes my photographs stronger.

As a whole the YPJ has made tremendous gains. They defeated ISIS in Kobane, which was a huge gain. They’ve also gained many more cities and territories in Syria that were previously occupied by ISIS. I do plan on continuing to photograph the YPJ, but unfortunately it has become a bit more bureaucratic and difficult to cover as restrictions for journalists have tightened in the area.

AB: You're based primarily in Iraq and India, but have spent a lot of time working in Syria. What are we in the West just not getting about what's happening on the ground in Syria?

ET: I am new to the Syrian conflict myself, but I think the big picture is that Syrians are suffering immensely, day in and day out, since the start of the conflict in 2011. Previously they suffered because of Assad’s military fighting the free Syrian army, but now they're suffering mainly because of ISIS. I think the most acute problem is the absolute disparity of the current refugee crisis and the destitute conditions. There is a total wipeout of government and infrastructure, food and water shortages, no medical supplies or resources, millions of people traumatized. Over two million people have fled the country and now live in overcrowded, refugee camps.

The West tends to get overwhelmed by the media and then gives up trying to understand what’s happening. A lot of people think, “These people (from the Middle East and Asia) have been fighting for thousands of years over religion and land, nothing is going to change that,” which is a gross misconception. It’s also an easy way out of trying to understand an issue. I tell people to imagine this happening in their own backyard or to their relatives — how would they feel then? Most people in the West can get online and find information on the Syrian war, but people aren’t motivated to know because they don’t feel like it affects them. The Syrians are ordinary people who for the most part had normal lives before the war, just like many westerns. They want to go about living their lives again in a peaceful place to raise their families. They didn’t expect this sort of thing to happen to them. It’s a difference between an “us” / “them” mentality and a “we” mentality.

Editor's note: Since publication of this piece, photojournalist Erin Trieb reports that several sources she’s spoken with claim the YPG (the male counterpart of the YPJ) have begun forced recruitment of youth and students in Syrian Kurdistan and have made threats to young Kurdish Syrian males who won’t join the YPG ranks, causing some families to flee the area.

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!