"Gold Fever" book cover.

“Gold miners call it ‘color,’” Steve Boggan tells me. “They speak about it in almost religious terms.”

Boggan’s explaining why gold fever — that crazy gleam in the eye some people get thinking about finding a honking chunk of ore in a river bed — isn’t like making a big business deal or winning the lottery.

“It’s transcendent,” Boggan says. “You’re bringing pure wealth out of the ground, creating it out of absolutely nothing.”

He should know.

A few years back, he chucked his relatively comfortable life in London and lit out for California, on the trail of the new gold rush. He didn’t get rich, but he did write a book about the experience. It’s called “Gold Fever: One Man’s Adventures on the Trail of the Gold Rush.”

"Gold Fever," both the book and the actual condition, snuck up on Boggan gradually.

The story starts back in the spring of 2008, when the price of gold topped $1,000 an ounce for the first time in history.

Boggan started to wonder if people were once again hoisting pickaxes and pans and heading for the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

He sold the idea of a story about "a new gold rush" to a British magazine, and headed for California. There, he found a whole new generation of hopeful, some might say deluded prospectors.

“They weren't finding very much,” says Boggan. “And on the one hand I thought these people were vaguely insane. But on the other hand, I found that I admired them. There aren't many things other than gold that will make people cast aside doubts, and just keep trying again and again and again.”

Boggan went back to Britain, and wrote his story.

Gold bug avoided, right?

Then, a couple of years later, the price edged above $1,900 an ounce.

“Privately, I made myself a promise. That if it ever went through $2,000 an ounce, I'd go back and try myself,” he says.

It never did, but that hardly mattered to Boggan.

“I thought, what the heck, I'm going to go anyway. So in spite of the fact my fiancé thought I was crazy, my family thought I was crazy, and all my friends thought I was completely bonkers, I got on a plane and flew to San Francisco.”

Imagine it. An Englishman pitching up in the American West, hell bent on finding one of Earth's rarest metals, with no equipment, no skills.

No clue, really.

“You know that the odds are stacked against you, but you buy the ticket anyway,” Boggan says with a chuckle.

He did enough research, though, to know he was in good historical company.

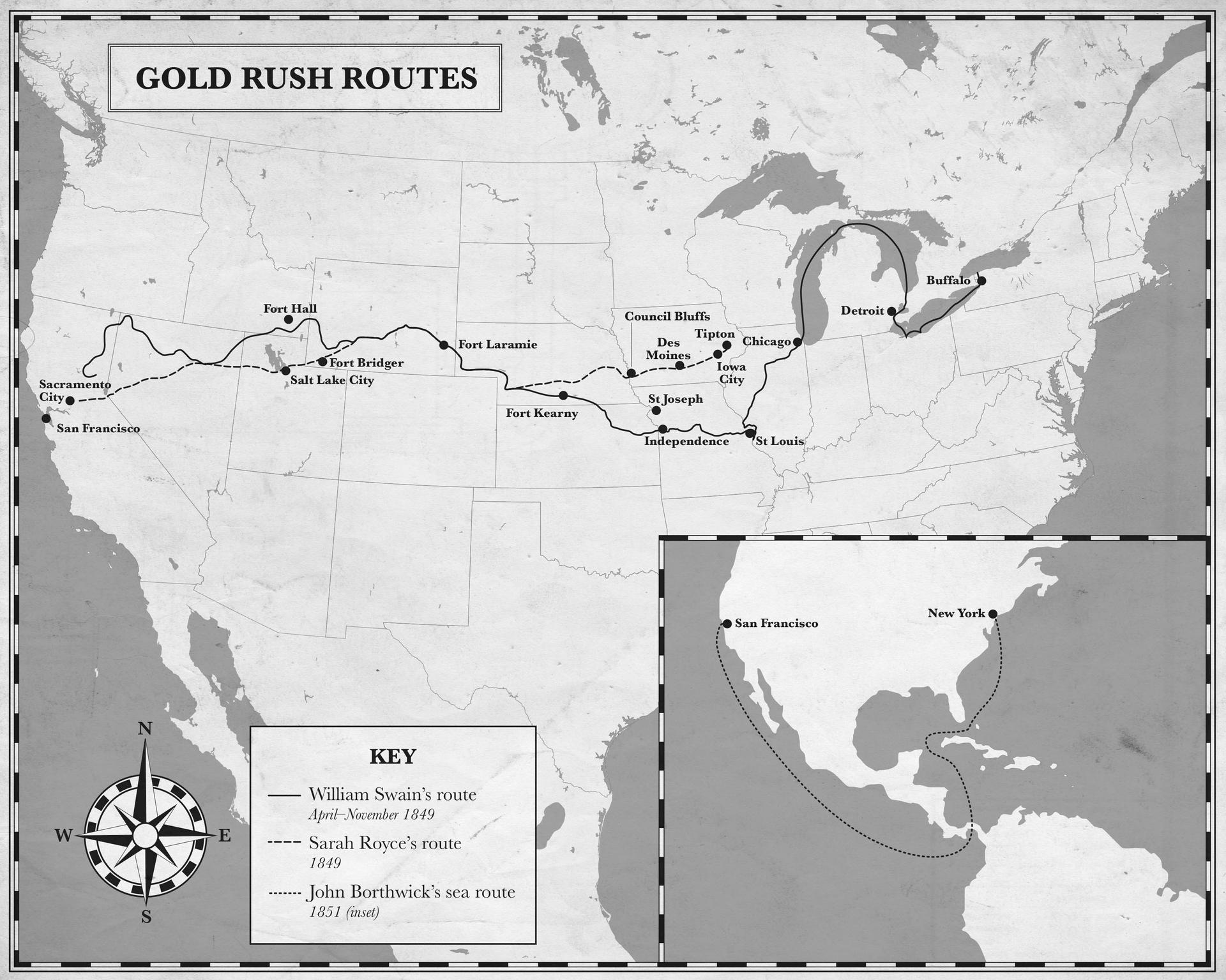

Back in the Gold Rush of the late 1840s, some 350,000 people descended on California. They came from all over the globe, in hopes of hitting the Motherlode.

“This was possibly the largest international migration of people that the world had ever seen at the time. And it was a huge melting pot.”

These days, Boggan says, it's mostly Americans searching for the Motherlode. All kinds of Americans, he says, rich and poor, older and younger.

The one thing that tied them together, besides a healthy dose of gold lust, was that they were incredibly friendly and helpful to Boggan, the “limey greenhorn.”

“I imagined that everybody would jealously guard their gold, their secrets, and their skills. But it couldn't be further from the truth. In the first few days, one guy took me out to buy some equipment and told me what I need. Another guy showed me how to use it. Another guy gave me an education on where to look for gold. And another guy gave me carte blanche to prospect on his claims.”

The first rule of modern prospecting, Boggan learned, is that there aren't any cheats. You still need a shovel, and you need to put your back into it.

He learned that from a seasoned prospector named Bear River Gary.

“If you've ever tried to dig underwater into clay and gravel, and then pick your spade up and carry it through the water, it isn’t easy," he says. The first time I tried it, I had nothing on the shovel at all. Bear River Gary told me I dug like a Frenchman. It’s kind of his scale of international whimpishness. The French are at the bottom, followed closely by the English.”

Digging is only step one.

Then you have to take the dirt and sift through it all, using basically the same kind of pan they used back in the 1840s.

It's back-breaking, tedious stuff.

But then the first "Eureka!" moment comes.

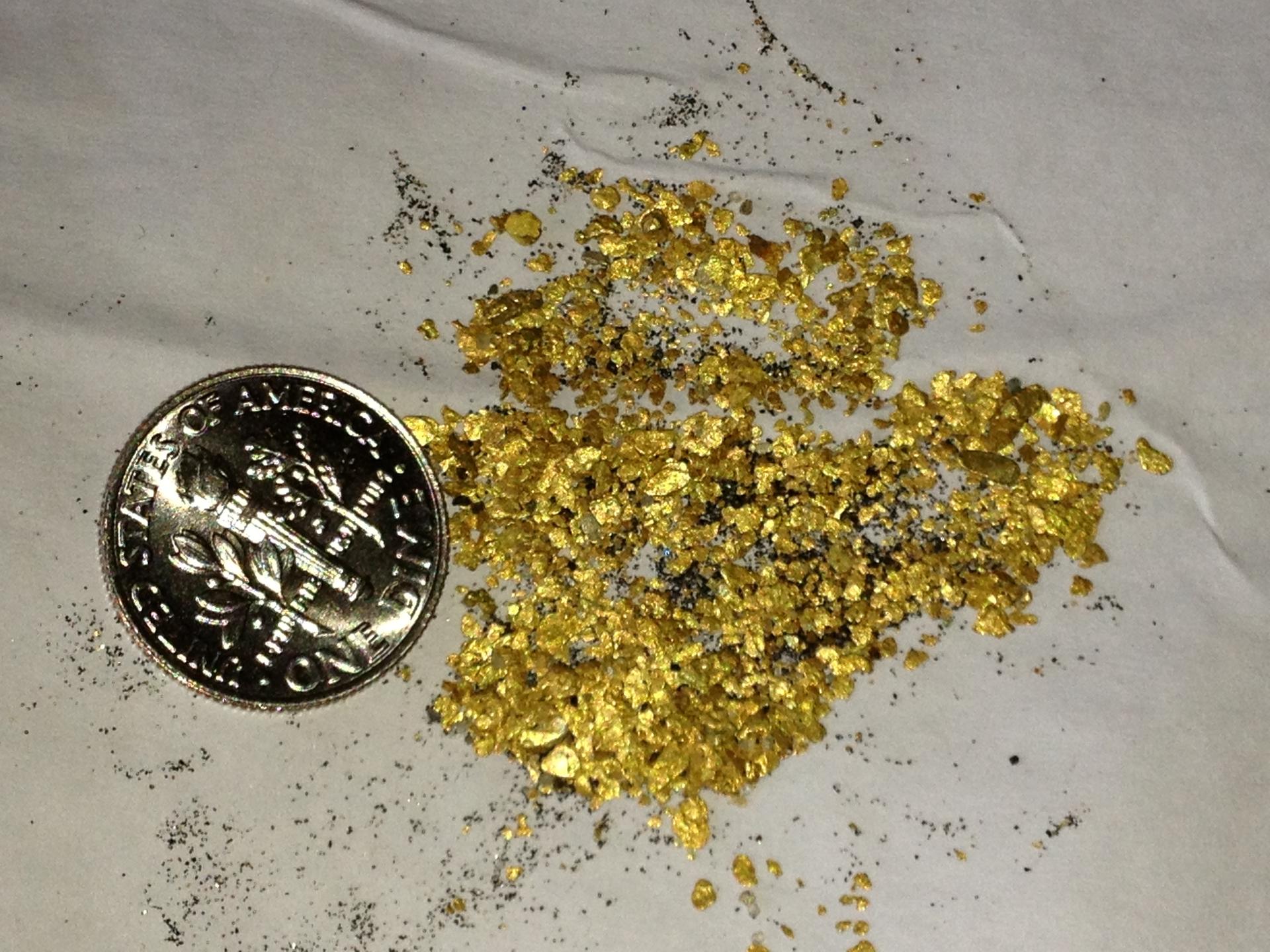

“I went down to the river, and I panned it out the way I had been taught," he says. "Well I did this, and I processed all of my dirt, and I got down and down and down until I had hardly any left, and in the last pan, there was one single flake of gold. And I can't describe the elation that you feel when you see gold in a pan.”

Boggan didn't strike it rich. But then again, hardly anyone does.

Boggan reckons, though, that maybe the gold isn't the real prize. Instead, maybe it’s being able to move freely from claim to claim, filled with the hope you'll pull pure wealth from the ground. You're working hard in the fresh air, surrounded by the stunning landscape.

“It's awe-inspiring," he says. "It’s a kind of freedom. It's a wonderful feeling.”

Especially, Boggan says, when a guy like Bear River Gary finally tells you, “’Hey, you're finally digging like an American!’"

Listen to Steve Boggan read from "Gold Fever."

Finding gold for the first time.

Finding gold is so much better than finding anything else.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?