A-bomb survivors: My mom and her mother Jettie on board the ship Oranje, which had been a hospital vessel during the war. They were on the boat’s first post-war civilian transport, making the crossing here from Java to Melbourne, Australia in November 1945.

I was in my 20s when I came to fully appreciate the contradiction of my mom’s life: Had it not been for The Bomb dropped on Hiroshima, she very well might not have survived the Japanese prison camp in Indonesia.

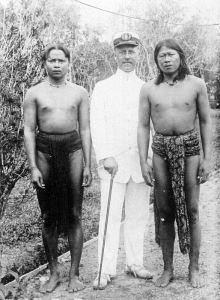

My mother, Marjolijn deJager, was born to a colonial Dutch family in the East Indies. Her grandfather was the Governor General of Aceh, and shuttled between his fulltime life there and The Hague. His daughter Jettie, my mom’s mother, married Jacob, an engineer with Royal Dutch Petroleum. On my mother’s side, I come from imperial/plunderer stock. It’s not a pretty legacy. It’s the luck of the draw.

When my mother was 5, the Japanese put her and Jettie in one of these camps, and Jacob in a men’s camp. My mom and Jettie would be assigned to two other camps over the next three years.

Mom talks freely about the experience if prompted. And I asked her again recently about the end of the war, and what details she remembered about Hiroshima, and August of 1945.

She was 8. On August 6, the day the US dropped the first of two atomic bombs on Japan, Mom and her mother were in Camp Makassar in Jakarta, still Batavia at the time. Mom has no recollection of the event. But her mother got word of it through her brother Baas. With the first wave of reports about the blast from Japan, security began to crumble immediately, and Baas was able to slip out of the neighboring men’s camp and share what he knew about the bomb with my grandmother. “They spoke half the night sitting in a ditch outside Makassar,” Mom tells me.

On August 12, with Japanese soldiers melting rapidly away, the Dutch camp head, Mrs. Witvoet, gathered the 2,000 or so female prisoners in the roll-call field and told them the war was over.

Mom says that by the end of August, they were officially released from the camp, but had nowhere to go. They finally ended up at a smaller compound in Jakarta, surrounded by Indian Gurkhas who guarded them from angry Indonesians, many of whom Mom recalls “were roaming the streets with guns and daggers to kill whatever ‘blanda’ (white) they saw.”

Unlike the German side of the Axis powers, Japan did not have a overt policy to eliminate an entire population. But as Mom learned years later, near the end of the war, Japan was running out of food — for itself and for its prisoners — and as 1945 marched on, killing those prisoners began to seem like the best option. You could say my Mom was saved by the bell, and the bell was The Bomb.

And that’s the contradiction. Mom described to me the uneasy and surreal notion of lives on a balance beam that she reflects on at times: “Some 100,000 women and children in dozens of camps all across the Indonesian islands. But then, in our place, all those innocent civilians in Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended up dead or maimed for life.

"And I cannot say that this makes me happy, although I am very glad to be alive, of course. But why me and not they? A rhetorical question. It’s really the luck of the draw.”

Editor's note: In 2011, Marco Werman traveled to Japan to report on the aftermath of the March 11 earthquake and tsunami that struck the region for our partners at PBS Frontline. Watch "The Atomic Artists" here.

See more stories from Hiroshima Generations series, supported by the United States-Japan Foundation. And check this app to see how a Hiroshima-sized bomb would have affected your hometown.