Prostitutes want Tunisia’s red light districts to get back in business

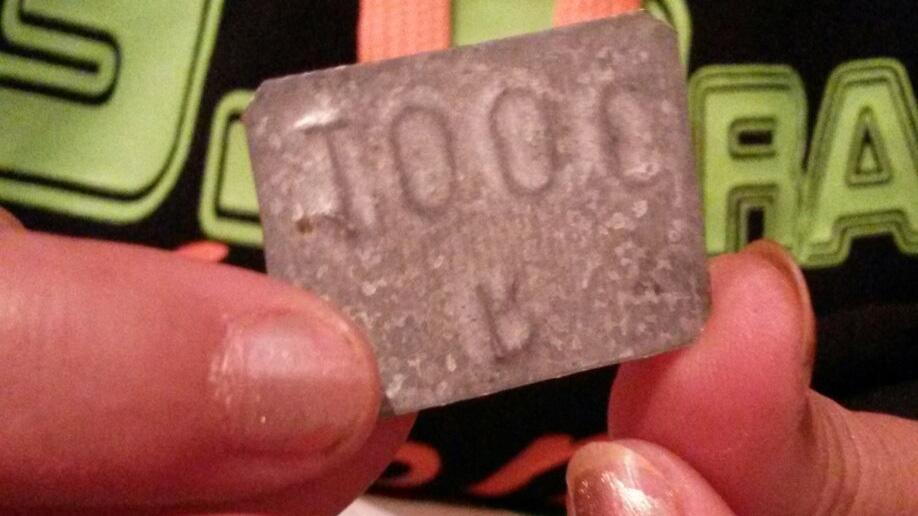

One of the tokens that johns in Tunisia use to pay prostitutes.

Just a few streets away from the blue-doored houses of Sousse’s old town, one alley stands derelict and abandoned. Patches of wild grass have grown in amid the trash and rubble. Graffiti painted on the walls reads “Go away.”

The message was directed at Rathia, and the 90 or so other women working that alley.

“We literally had to run for our lives,” says Rathia, as she remembers the day her neighborhood, and business, went up in flames. “They came here and they just torched the places. We had to run out or we would have been burnt.”

Rathia was the supervisor of a brothel, home to four sex workers. From a plastic bag, she pulls out the metallic chips she sold to clients for 10 dinars each — about $5.50. They’d give it to a prostitute, who would collect her money from Rathia at the end of the week.

“For me and my girls, the idea was that they wouldn’t pay anything," she says. "I would cover the rent, the cook, the cleaning, all of that. But the income would be split 50/50." That's less than $3 each per client.

Rathia became a supervisor in 2008. For 13 years before that, she was one of the “girls.” She got into the business after her husband left her. She was just 21, had three young kids and had no other choice, she says.

Her story might sound sadly familiar all over the world, but what comes next doesn't. Rathia went to court and got a license to be a prostitute. She started working in Sousse, a tourist town that was home to Tunisia’s second largest red light district.

That's because prostitution is legal in Tunisia, one of only two Arab countries that allow the trade. Red light districts have been legal in Tunisia since the time of French occupation, and the brothels there are run like any other business, with taxes and regulations.

Rathia says the red list districts offered a home and income to penniless women, and provided jobs for hundreds more. “It wasn't just a place for girls to come and work,” she says. “It was open to a lot of the poor to come and help out and make a living in different ways. Between cooks, cleaners … hundreds of families were living off of the red light district. It was a community.”

But not all Tunisians saw it that way. Shortly after the 2011 revolution that toppled Tunisia's longtime president, Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, Islamist groups ransacked red light districts across the country and forced most of them to close.

“They came in the daylight and just attacked us," Rathia says. "They left nothing for us. Clothes, furniture, electric cables … everything was ransacked, stolen or destroyed.” Only two red light districts remain open: one in Tunis, the capital, and one in the Mediterranean port city of Sfax.

As Rathia talks, her phone rings. “This is one of the girls who used to work with me,” Rathia explains while still on the phone. "Now she’s working in Sfax."

We meet Sahar, the woman on the other end of the line, in Sfax the next day. The red light district looks like Sousse used to: Women are sitting on doorsteps of a narrow street in the old town, waiting for clients. Inside a house, it’s spotless.

Sahar, sporting a blond bob and carefully made-up brown eyes, says it’s not as busy here as it was in Sousse. There are fewer tourists and less money. But the main problem for her is that the city is a two-hour drive from her three childeren, who stayed in Sousse.

Sahar used to go home every night to her children. Now she leaves them for a month at a time, and shells out most of her meager income for a full-time nanny.

"It's very difficult for them, especially the oldest, because they understand the fact that it’s their mum and she’s going away," she says. "Just about every time I leave they end up in tears and they want me to stay. They get over it pretty quickly, but then it starts again every time I’m back."

Sahar says the family would be homeless if she wasn’t working. And with the district in Sousse closed, staying there wasn’t an option. Some women started working illegally, but she says that’s too risky. The red light district offers protection — and even access to health care.

Dr. Abdelmajid Zahaf checks up on Sahar and the other women twice a week. He's been running a clinic for sex workers in Sfax for more than 30 years, and says red light districts offer a public service, allowing the women to work in the safest environment possible.

"The women who work illegally, they could have HIV and nobody would know about it! They also rarely have a place to stay. Some of them tell me they sleep on the streets," Zahaf says. "Others talk about abuse and violence, because when they are picked up and go off with somebody, they have no idea where they are going, they don’t know if its gonna be 1, 10, 20 guys waiting for her there."

And when things go wrong, illegal workers don't have much recourse, he says: "They can’t go to the police, they have no rights. There’s just no comparison between what goes on illegally and the safety of houses that are being monitored."

When Islamists started to attack red light districts in 2011, Zahaf says neighbors gathered with sticks to protect the entrance of the street in Sfax. Some even threatened to attack a nearby mosque if Islamists made trouble.

Now Zahaf is helping women to rehabilitate the abandoned districts. "It’s a matter of political courage," he says. "All it takes would be to clean up the neighborhoods and get police back to secure the area."

Rathia, the supervisor in Sousse, was part of a group of women who petitioned the moderate Islamist government earlier this year, but their plea fell on deaf ears.

Now she hopes the secular coalition that won the elections in October will be more friendly to their cause. For her, and dozens of others, the reopening of red light districts can't come soon enough.