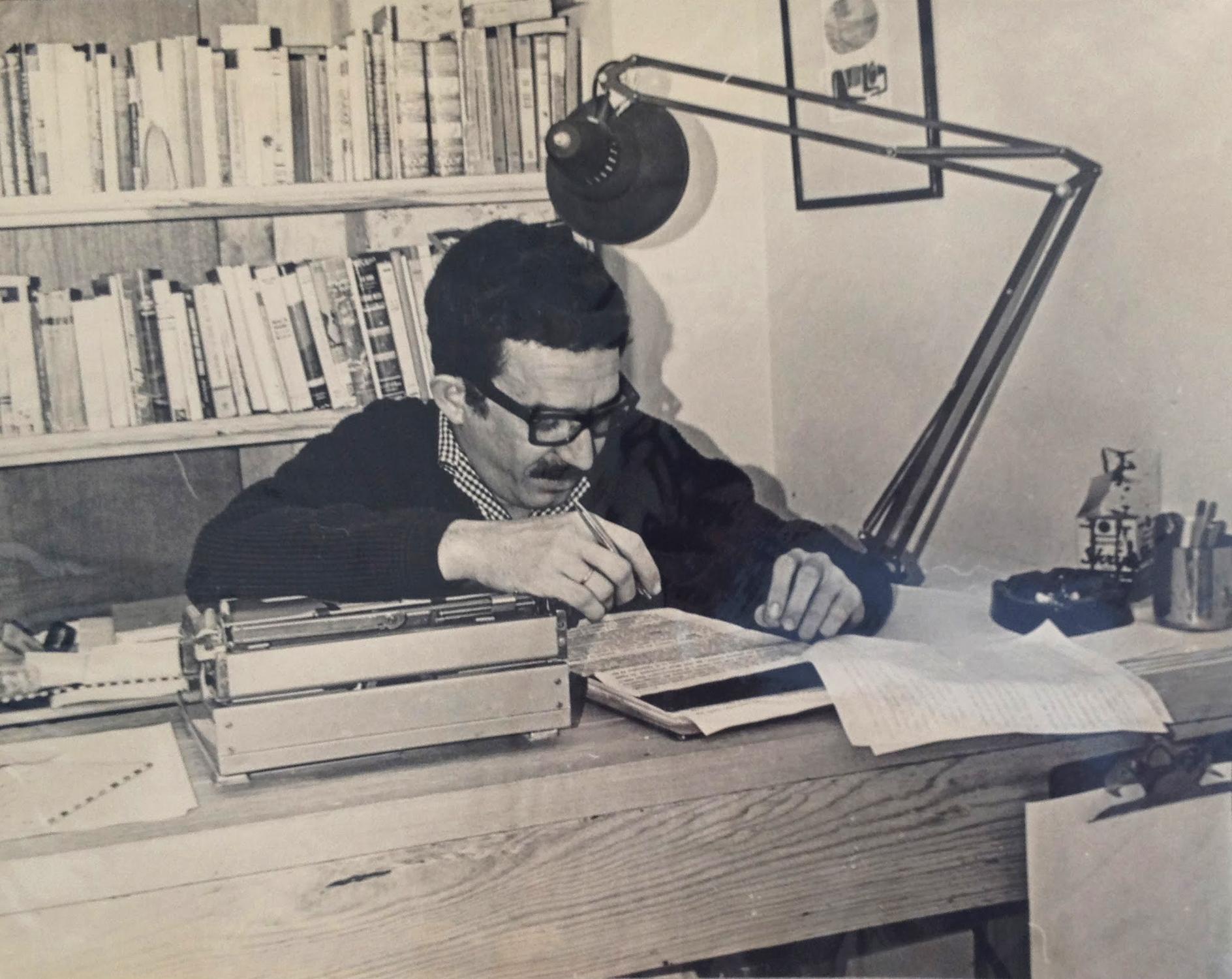

Gabriel García Márquez working on "One Hundred Years of Solitude."

It's one of the most famous opening lines in the history of literature: "Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice."

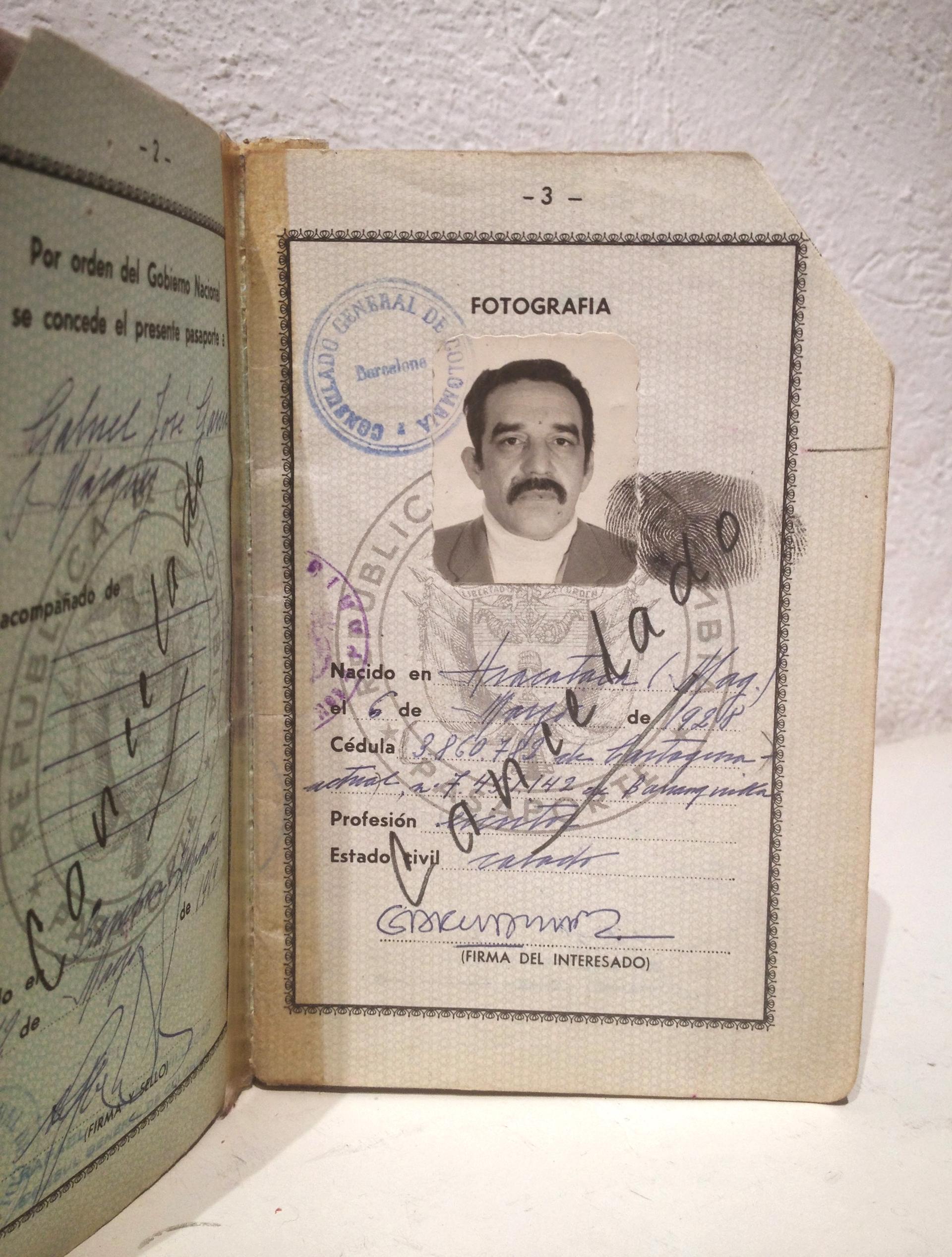

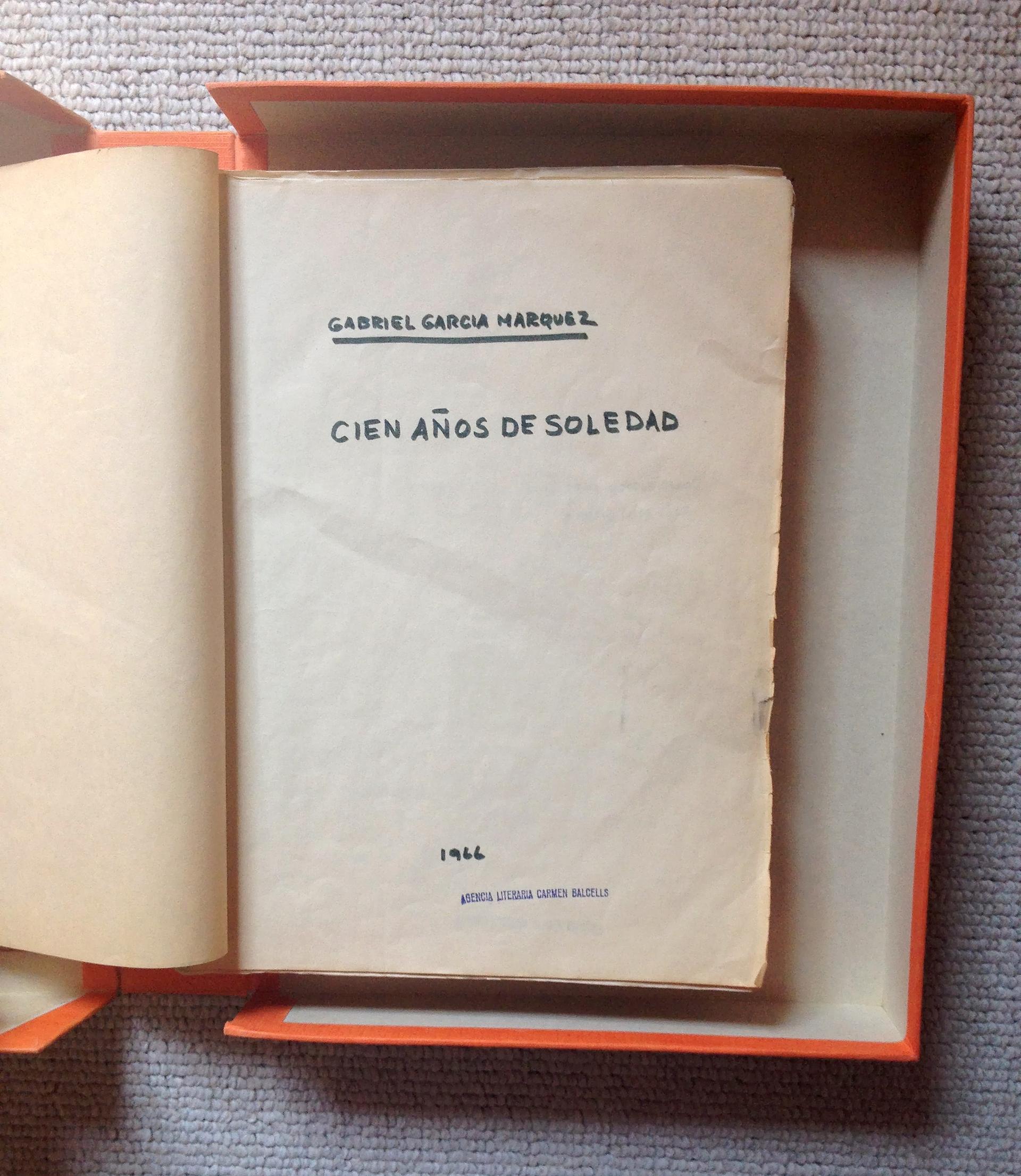

Now the original manuscript of the book where those lines appear — "One Hundred Years of Solitude" — is on its way to Texas. The lion's share of the archive from Gabriel García Márquez, the late Nobel Prize-winning author, has been acquired by the University of Texas, Austin, where it will be housed in the Harry Ransom Center, a humanities research library.

"There are plenty of literary manuscripts with handwritten corrections by García Márquez," says UT librarian Jose Montelongo. "There are lots of photographs that document the life of an author that became very reclusive because of the fame he achieved. It's a fantastic archive of one of the most beloved Latin American authors of the 20th century."

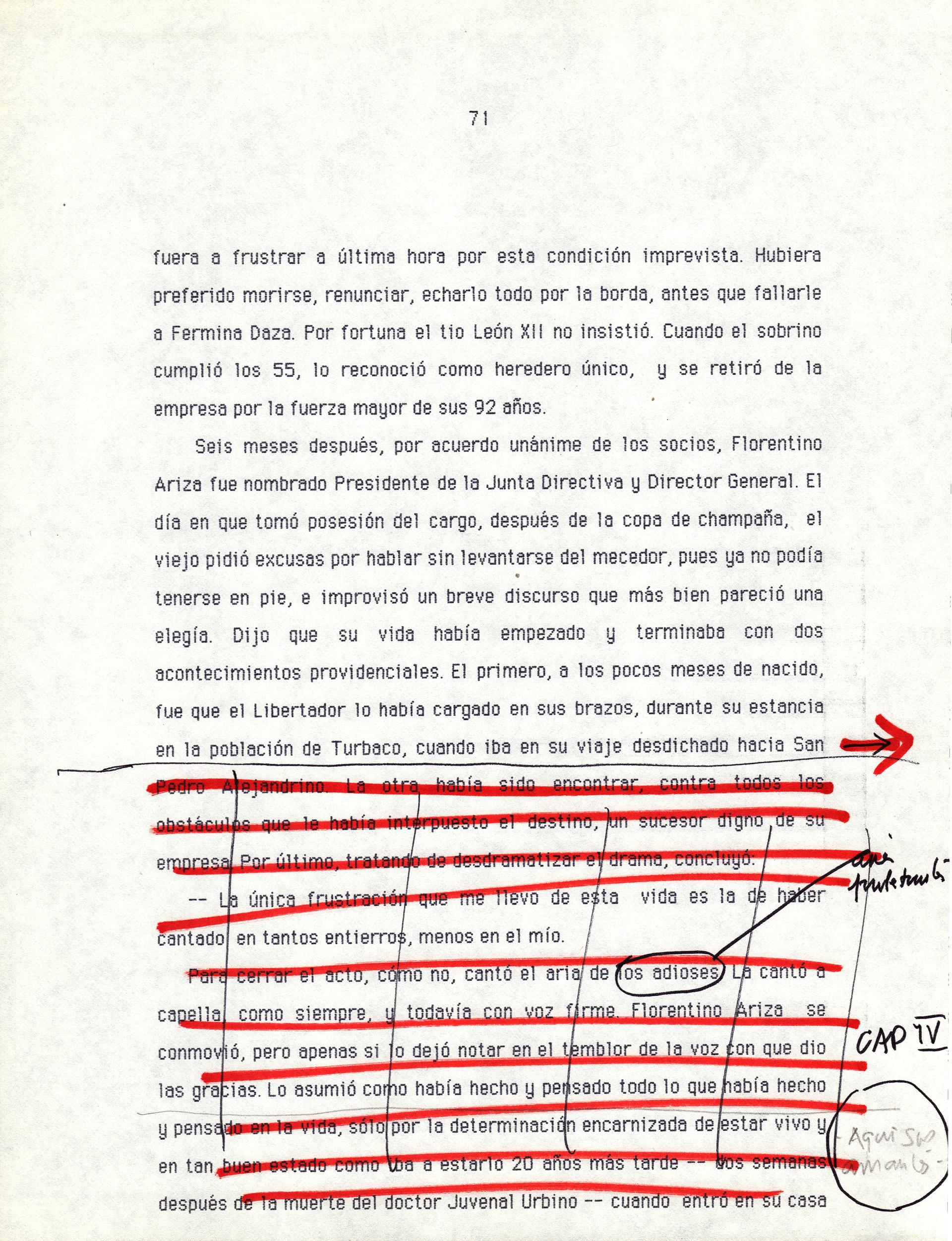

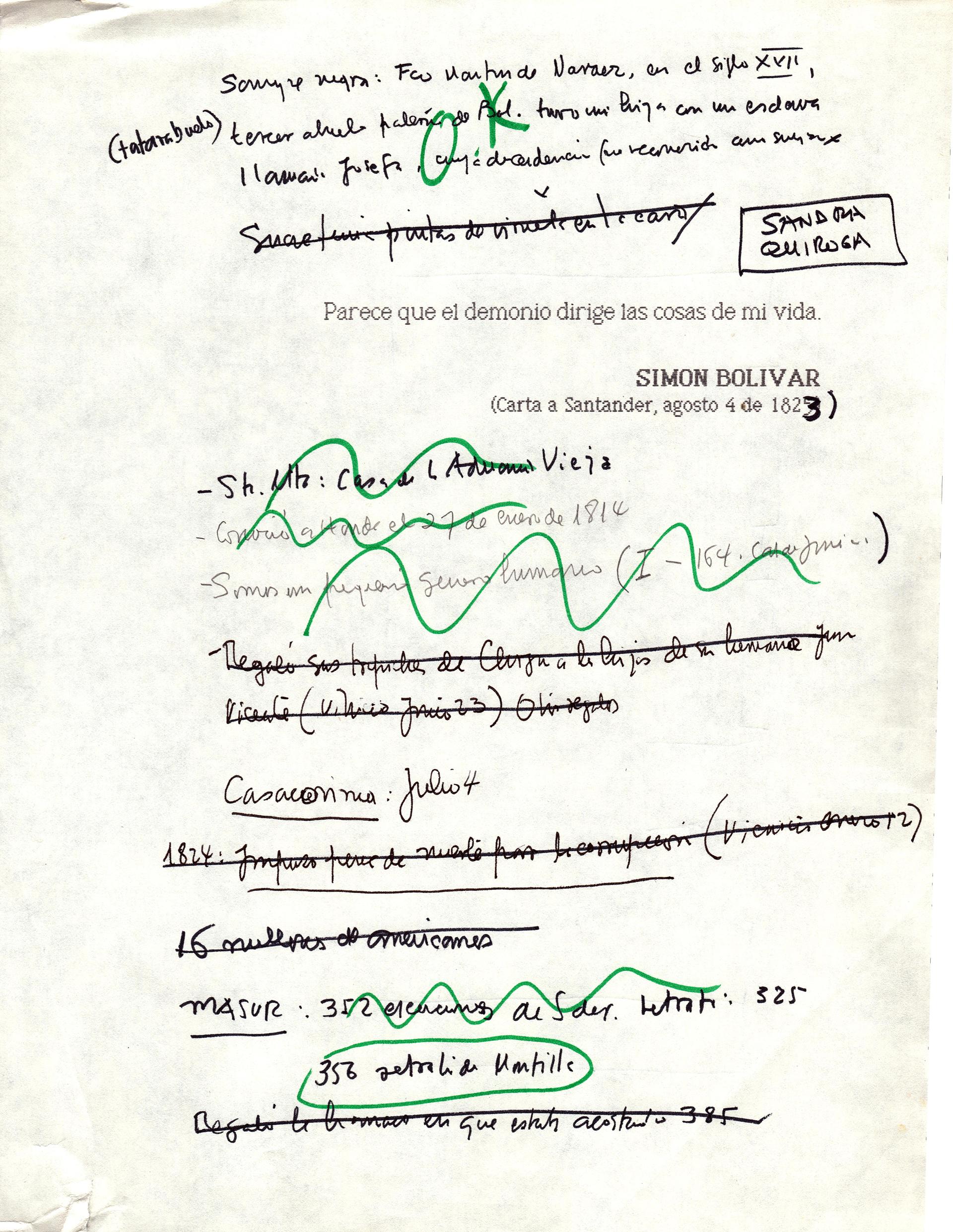

The original manuscript for "One Hundred Years of Solitude" also includes a couple of corrections — yes, even a masterpiece had mistakes.

But Montelongo says they give the readers a rare window into García Márquez's process and how he edited himself. "To see the crossed out words, paragraphs, revisions … To see it is to see García Márquez in action," Montelongo says. "It's a treasure for anyone interested in artistic creation, in the art of narrative."

The archive allows researchers, students and, soon, fans the ability to understand his process.

Montelongo says the drafts and notes of García Márquez's early works are few and far between. "We don't have many clues about his early work as a writer," he says. He suspects that, at this phase in the writer's life, García Márquez was more concerned with survival than with posterity.

That started to change later in García Márquez's life. He kept his works in progress, including a previously unpublished novel. Montelongo says García Márquez was working on it for at least the final 10 years of his life.

"We have close to 10 versions, 10 drafts of that novel in which you can see him really working through problems of structure, of characters, of atmosphere," he says.

García Márquez never got the novel up to his standards before he died, but there's a possibility it could still be published. Montelongo says that decision is up to the family, which owns the copyright to the work. Yet they face a tough question in publishing it posthumously: Do you send an unfinished work out to the public? Or do you keep it in the archive for educational purposes only?

It's a tough question for the family of a man who is considered "The Latin Homer." You want to follow what he thought was right for his own work, which isn't always what happens — see the case of "2666," a novel by another beloved Latin American author, Chile's Roberto Bolaño.

For Montelongo, having this archive in his backyard is unreal. He specializes in Latin American literature, and having the García Márquez archive in Texas is the motherlode for that field.

He says looking at the corrected manuscripts feels a little illicit — in a good way.

"I've been reading about what they call, 'pentimente,' Montelongo says. "These are the brush strokes that you can barely see underneath the final brush strokes. And when you are talking about great painters, it is so important to be able to see not only the final work but the stages of that work. It gives you the sense of internal debate, struggle."

It turns out the same goes for literature, he says. "Seeing great artists struggling with form, it is the most exciting thing for somebody like me and for anybody interested in Latin American letters."