Families that are deported after crossing the border say they return home feeling hopeless and desperate

Salvadorans listen to a local immigration agent after arriving with other deportees from the US at Salvador’s international airport in July. Every day, an average of 120 Salvadorans arrive in the country after being caught attempting to cross illegally into the US, Salvadoran immigration authorities said.

On a weekday morning in late August, an American plane arrived at the airport outside of San Salvador, El Salvador’s capital, bringing back deportees from the United States.

Among them were nine children and their mothers who had been held in a temporary family detention facility in the remote town of Artesia, New Mexico.

Relatives of the deportees gathered outside the terminal. An orange awning shielded them from the bright morning sun as birds chirped loudly from nearby trees.

So far this summer, 288 women and children have been deported from the facility in Artesia. This flight was the third to land in El Salvador.

José Angel waited with his mother-in-law to pick up his 23-year-old wife, Sonia, and his 5-year-old son. The two were detained in Artesia for a month and a half. They left El Salvador on July 4.

“She went to ask for asylum because she was being threatened,” José Angel said in Spanish.

Sonia had a small chicken farm in El Salvador that her family said made her a target for extortion by local gang members. Sonia’s mother, Judith, said it is common for gangs to charge business owners "rent.” She said her family had already fled this situation once before. They used to run a tortilla business in a different area but left because of those threats, only to find the same problems in their new town.

Judith said she knows several people who have been killed for not complying with gang demands for money.

It’s risky to talk about, which is why the family didn’t want their last names used in this report. Still, Sonia’s story didn’t impress the asylum officer who interviewed her in Artesia.

“They said in an interview there that her case wasn’t credible,” Judith said.

Arriving migrants who are held in detention and placed in expedited removal proceedings — as Sonia was — must prove they have a credible fear of persecution back home in order to pursue an asylum claim in the US.

“There were a lot of people who had good luck,” Judith said. “Where we live, a lot of women with kids went [to the US] and they made it through. Sadly, she was not one of them.”

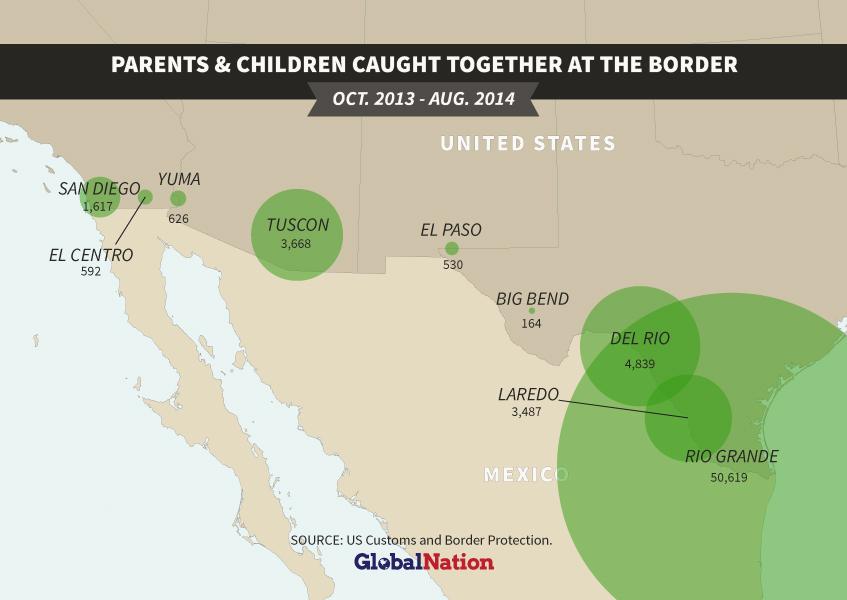

Almost 63,000 migrant families, mostly from Central America, have arrived at the southwest border since October, a 471 percent increase from last year. The vast majority crossed into Texas' Rio Grande Valley.

Many turned themselves in to US Border Patrol agents and were released to bus stations to join relatives while they await deportation hearings.

But the Obama administration is trying to discourage migrants from entering the US illegally. One way is by detaining more arriving families and expediting their deportations.

The federal government opened the Artesia Family Residential Center in late June. It’s on the grounds of a federal law enforcement training center, and has capacity of up to 700 women and children. An immigration detention facility in Karnes City, Texas, outside of San Antonio, also started holding arriving families this summer.

Back at the airport

Sonia and her son were about to be released, but their relatives must pick them up in a secure area where reporters aren’t allowed. I lost my chance to meet them.

But I talked to Sonia later on her cell phone. She said she left Artesia voluntarily once she she learned she wasn’t likely to win her asylum case. A Salvadoran migration official said the other women returned from Artesia had also agreed to voluntary departure.

In Sonia's case, she could have waited to see an immigration judge to ask for a second credible fear ruling, but she felt it was hopeless and was anxious to leave.

“I left because my son wasn’t eating,” Sonia said. “The chicken was raw, it was even bloody.”

She said her son had a fever for eight days and she couldn’t get him medicine at first. Other detainees have made similar claims.

Sonia also said she wasn’t able to talk to an attorney until after she had already had her interview with an asylum officer. Allegations like that, along with several others, have been compiled into a recent federal lawsuit claiming a lack of due process for women and children in Artesia.

A coalition of organizations, including the American Civil Liberties Union and the National Immigration Law Center, are behind the suit. They filed it in federal court in Washington, DC, on August 22, the day after the plane carrying Sonia and other women and children landed in El Salvador.

“The fundamental issue at the facility is that it is not giving those women and their kids a fair day in court,” said Karen Tumlin, an Los Angeles-based attorney with the National Immigration Law Center.

It’s not clear if Sonia had a winning asylum case or not, but Tumlin said many women and kids held in Artesia do, and would face grave danger if they are returned home. But detainees in Artesia may actually be held to a stricter standard.

According to data from US Citizenship and Immigration Services, fewer than 38 percent of Artesia detainees were found to have credible fear, versus an average national rate of about 72 percent this spring.

The lawsuit alleges that Artesia detainees do not have adequate access to legal help, and volunteer lawyers who come to the facility have trouble visiting clients and gaining access to proceedings. It also alleges that women must recount stories of abuse to asylum officers and judges in front of their children since there are no childcare services at the facility.

At the same time, other recent developments in immigration law could allow more Central American women to prevail in their asylum claims. In a precedent-setting decision last month, the Board of Immigration Appeals ruled that Guatemalan women who flee life-threatening domestic abuse can be eligible for asylum.

That decision has helped one Honduran woman in Artesia win asylum already.

But Tumlin said the immigration court system in Artesia is speeding up proceedings to the point that there is not sufficient time for attorneys to prepare their client’s cases.

Instead, she said there is a “rush to judgment to deport as many these women and kids as quickly as possible.”

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which oversees the Artesia center, maintains it is facilitating access for volunteer attorneys who want to provide free legal services at Artesia.

"The inter-agency response to this unprecedented surge has been both humane and lawful," ICE spokeswoman Amber Cargile stated in an email. "As a matter of policy, we do not specifically comment on pending litigation."

In a separate email, ICE spokeswoman Leticia Zamarripa said the food served at the Artesia Family Residential Center is the same food served to students and staff at the adjoining law enforcement academy, and is not used as punishment or a reward.

Meanwhile, Sonia and her family are back living in the same house in El Salvador where she was threatened. I wanted to interview Sonia at her home, but she explained that would not be a good idea. She said the gang won’t allow unknown cars to enter her neighborhood.

“I haven’t left the house except to go to the store just now,” Sonia said. “Because it’s scary.”

She’s also broke.

She still owes the gang thousands of dollars. Plus she paid $6,000 trying to get to the US. That’s all gone.

Sonia said if she’s threatened again, she’ll likely move, perhaps to another Latin American country because it’s clear there’s no future for her family in the United States.