Why are Cesarean sections so common when most agree they shouldn’t be?

Marton Balla looks on as his wife, Kate Mitchell, undergoes a Cesarean section on February 17, 2013.

Kate Mitchell, 32, gave birth to her daughter in a manner she sought to avoid.

Leila, now 14 months, was born by Cesarean section, a final intervention Mitchell and her husband reluctantly agreed to after 40 hours of labor failed to progress. The Cesarean was the last thing they wanted when preparing their birth plan with a midwife in Boston.

“I constantly meet women who have very similar experiences to me,” says Mitchell, “where they were committed to having a low-intervention vaginal birth, and their providers were also committed to support them in that, and somehow they still ended up having a C-section. That’s the mystery to me. I don’t understand how that happens.”

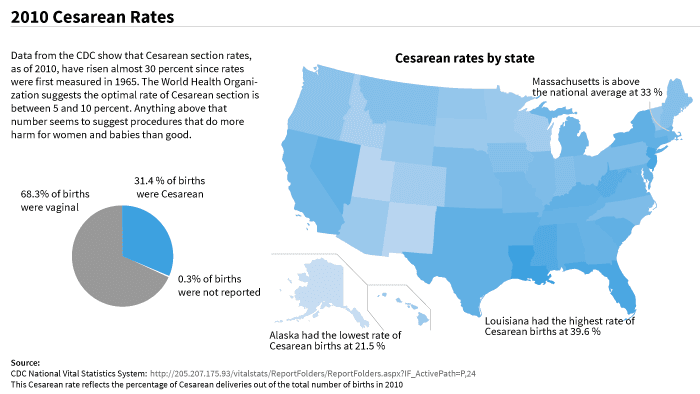

In the US, the C-section rate has skyrocketed in recent decades. In 1965, a little over four percent of all babies were born surgically. Today, that figure is one in three. There is little question that C-sections save lives in the case of serious childbirth complications, but the procedure also carries small, but real, risks. For the mother, there is the possibility of postpartum complications such as internal bleeding, infections and infertility. And babies delivered via Cesarean face an increased risk of breathing problems, juvenile diabetes, allergies, and asthma.

The World Health Organization, in a 2010 report, argued that no country should exceed a rate of 15 percent of total births via Cesarean section. Anything higher, the WHO concluded, indicates overuse. Yet 69 countries exceed that rate. According to the WHO analysis, the United States had the third highest number of unnecessary Cesarean sections in the year 2008, costing the country an estimated $687 million.

Mitchell’s interest in the rate of Cesareans stems not just from her personal experience. She works part time for a maternal health research program at the Harvard School of Public Health and is getting her doctorate in international health at Boston University. She has worked in maternity wards and rural clinics in the Dominican Republic and India. “The evidence suggests that a C-section is a more risky route of delivery than a vaginal birth,” she says. “So why are we delivering more and more babies in a risky way?”

The answer to Mitchell’s question, throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s when the C-section rate rose by 60 percent, was obvious to practitioners and hospital administrators: Cesareans relieved the labor and delivery units from mayhem and unpredictability, introduced order and efficiency, contributed clear profits to the hospital, and provided an alternative method of delivery for doctors worried about medical malpractice suits associated with complicated vaginal births. “There was a sense of complacency about it,” says Carol Sakala, childbirth quality expert at the National Partnership for Women and Families, a nonprofit reproductive health and rights advocacy organization in Washington, DC. “There were ideas of the inevitability of the prevalence of C-sections.”

Yet there is a now a widespread effort to bring C-section rates down, including in Massachusetts, where Mitchell lives. Hospitals throughout the state have increased training for staff in delivery rooms and introduced safety rounds and checks to reinforce standardized decision-making during deliveries. Some state hospitals have begun to overtly discourage elective C-sections, with some going so far as to tally physicians’ personal rates for Cesarean sections and compare them to other providers. Despite these initiatives, Massachusetts hospitals are not seeing a drop in Cesarean rates anywhere near the rate they rose throughout the last two decades.

One problem, experts say, has been a lack of clear guidelines specifying the circumstances under which a C-section is medically necessary, leading to a wide variation in the prevalence of Cesareans across hospitals. A study published in March of last year found that the C-section rates across Massachusetts ranged from 14 to 39 percent, with no differences in the condition of the patients that might explain the variation. “It really comes down to a difference in styles across hospitals,” says Sakala. “We need to rein in those differences.”

In an attempt to do that, this February the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued joint guidelines that call on doctors and hospitals to avoid Cesarean sections, even if it means letting first-time mothers remain in labor longer and push harder. The guidelines recommend letting first-time mothers push for three hours or more during labor. They also recommend using forceps to get the baby out vaginally.

“The publication of this new guideline is trying to suggest to obstetricians to handle things a little differently,” says Marian MacDorman, a senior statistician at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Certainly it’s easier for them and more profitable to turn to a C-section,” she says. “But I’m hoping with the publication of these new guidelines that maybe they can back off of those stances.”

Dr. Aaron Caughey, an obstetrician who co-authored the guidelines, says the recommendations are meant to provide crucial support to medical professionals who are worried about legal liability. “The moment [labor] takes longer than it should take, the doctor, midwife, the nurse, is hung out to dry,” Caughey says, referring to the fact that doctors are often quick to suggest a Cesarean at the first sign of fetal distress or delivery complications. With the guidelines, he hopes doctors will be more patient because they can show — in court, if need be — that they followed good medical practice. “We hope that these guidelines will provide a place of sanity, a way for clinicians to be patient,” he says.

Despite all the talk within medical circles about what doctors can do to reduce the C-section rate, another important piece in the puzzle is the mother herself. With increased education, she says, expectant mothers may better understand the risks associated with all delivery options, may be less likely to blindly follow an obstetrician’s advice, and may be more accepting of longer labor times.

For Mitchell, who underwent a C-section she sought to avoid, questions linger. “It’s still a really emotional thing for me to think about. And it’s confusing for me to think about, too,” she says. “I still ask myself all the time, ‘Is there something else that we could have done? Was there something that we didn’t try? Was it really necessary?’”

Mitchell's story, one where multiple realities intervened with a careful birth plan, is a common one during deliveries worldwide. The Ninth Month team wants to hear your birth story. Did you have a positive birth experience? Was it what you expected? Share your birth story with our interactive tool, and read stories from others, too.