Gabriel García Márquez influenced writers and readers all over the world

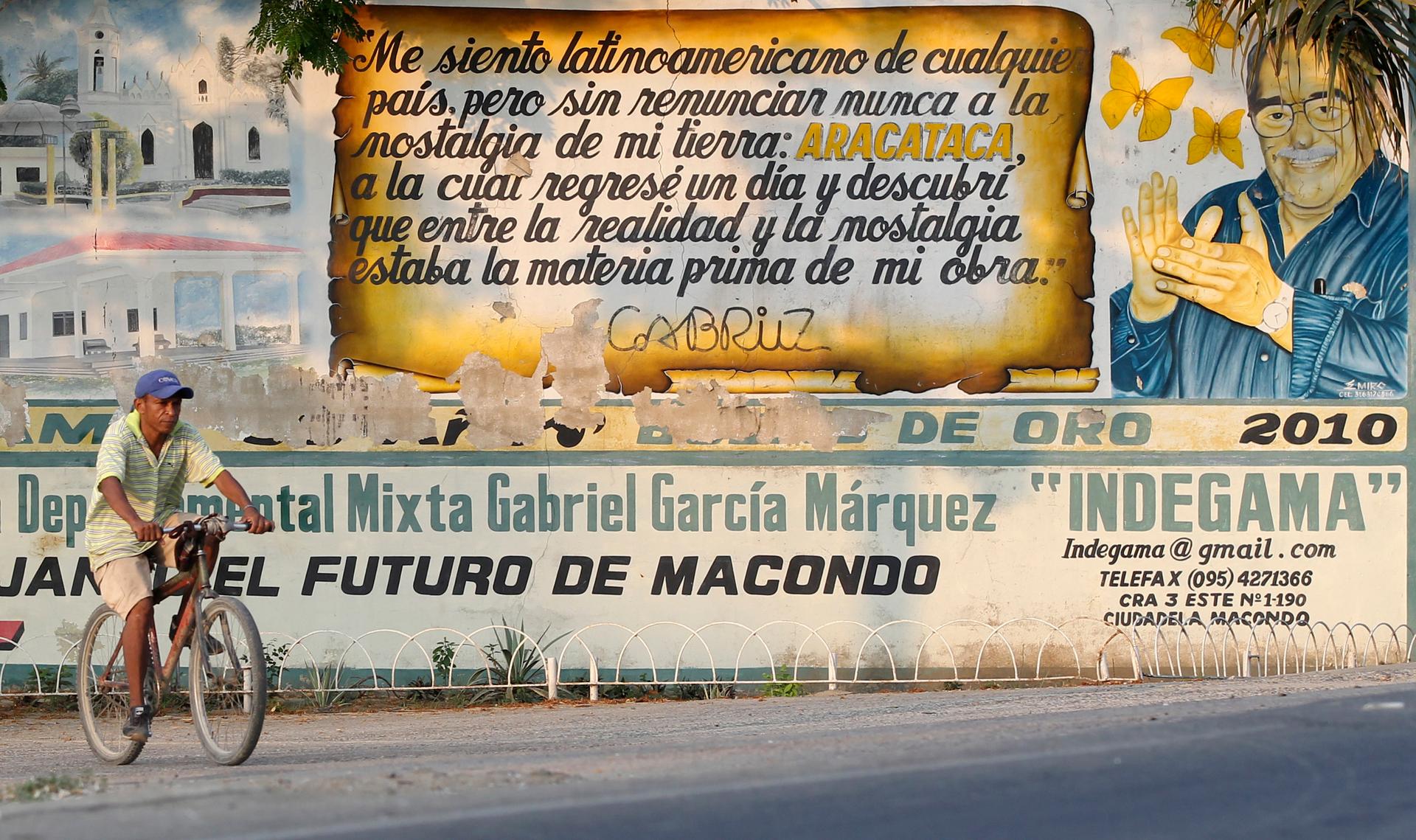

A man riding on a bicycle passes by a mural in honor of Colombian author Gabriel García Márquez, in Aracataca, the author’s birthplace. Photographed on April 18, 2014.

Gabriel García Márquez, a Nobel Prize-winning Colombian writer best known for his novels One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera, saw himself as a journalist first and a novelist second. And as a realist above all.

He died Thursday in Mexico City.

Because of his writing style, he's often credited as a pioneer of the magic realism literary genre.

"I invent nothing," he once told the BBC about his literary style. "People always praise my imagination, but I believe I am a terrible realist. Everything I invent was already there in reality."

Many in Latin America agree that there's nothing magical about the way García Márquez described people and places, even if his characters were visited by ghosts, or floated impossibly far above the ground.

Writer Daniel Alarcón, a frequent contributor to The World and co-founder of Radio Ambulante, says García Márquez's writing came from a rich tradition of storytelling and oral history.

"I remember, a couple years ago when I was in Cartagena [Colombia] and I was in a cab and the cabbie was like, 'This is Gabo's house,' and he says, 'Here in the Caribbean we all have great stories, he's just a good typist,'" Alarcón recalls.

Alarcón wouldn't use the label "magical realism" to describe García Márquez's work, though. Instead, he believes García Márquez depicted a certain kind of reality — the kind found in Macondo, the fictional town in One Hundred Years of Solitude.

"I'll give you an example," Alarcón says. "There's a bus company in Peru, in Lima. Turns out there's a bunch of fake buses that have painted their buses exactly the same and are running the same route and they are not a part of the company, but everyone thinks they are. And they are stealing passengers from the real company. You know that's 'Macondiano.' You realize you are in a world with its own logic."

García Márquez also influenced writers beyond Latin America. Hamid Ismailov, a novelist from Uzbekistan (and the BBC's official writer-in-residence) says he began writing in the Soviet Union around the time of García Márquez's first literary breakthroughs.

Ismailov says Márquez's work had a huge impact on writers, like himself, from small villages.

"His One Hundred Years of Solitude was completely different to everything we were reading about at that time," Ismailov says. "It was neither the Soviet literature nor the American or the Western literature. It was the third-world literature. And it made us look at our own roots and all of a sudden to remember how magical our literary tradition is. For example, One Thousand and One Nights is in our literature. It helped us to rediscover ourselves."

García Márquez also wasn't seen as a threatening, anti-Soviet writer, and his work became wildly popular in the USSR.

"Then other books of Márquez appeared, like Autumn of the Patriarch or No One Writes to the Colonel, which were absolutely, in a sense, anti-Soviet ones. But the floodgate was already open," Ismailov says.

So readers and writers alike readGarcía Márquez and were shaped by him.

"He helped to create the talent of Fazil Iskander, an Abkhaz writer who famously wrote Sandro from Chegem. Once again, the village in the middle of nowhere was taken as the center of the world. And everything was happening somewhere — but not in Moscow, for example, or not in St. Petersburg or not in New York or Washington. So, little by little, the value of the ordinary life was creeping in with the help of Márquez's books," Ismailov recalls.

Ismailov describes it like this: "Storytelling is such an important part of human being and with every story it is human nature to add something sort of magic, something kind of hyperbolic. When you are telling stories, you are sometimes hyperbolizing. And that was the essence of the technique of Márquez and he released this technique for the whole world."