Muslim American men share their stories of love and intimacy in a new book

Mohammed Shamma, an Egyptian American in Berkeley, contributed to the anthology,”Salaam, Love.” He writes about the cultural consequences of his first kiss during a game of spin-the-bottle.

Growing up, I lived in what you’d call a “secular Muslim” household. My family didn't pray five times a day, and we ate bacon — but there was one rule my parents always held on to: no boyfriends.

As a teenager, I wasn’t supposed to look at boys, or even think about boys. And I wasn't the only one.

In Ayesha Mattu’s last book, “Love, Inshallah,” she talks about these sorts of challenges for Muslim American women. The book got a lot of media attention, but Mattu and her co-author realized quickly they only had half the story — when they began to hear from Muslim American men.

“We were receiving emails by men who had read the first book,” Mattu says. “We were being stalked at dinner parties. We were stopped on the streets by our [male] friends and acquaintances saying, ‘Where are our stories?’”

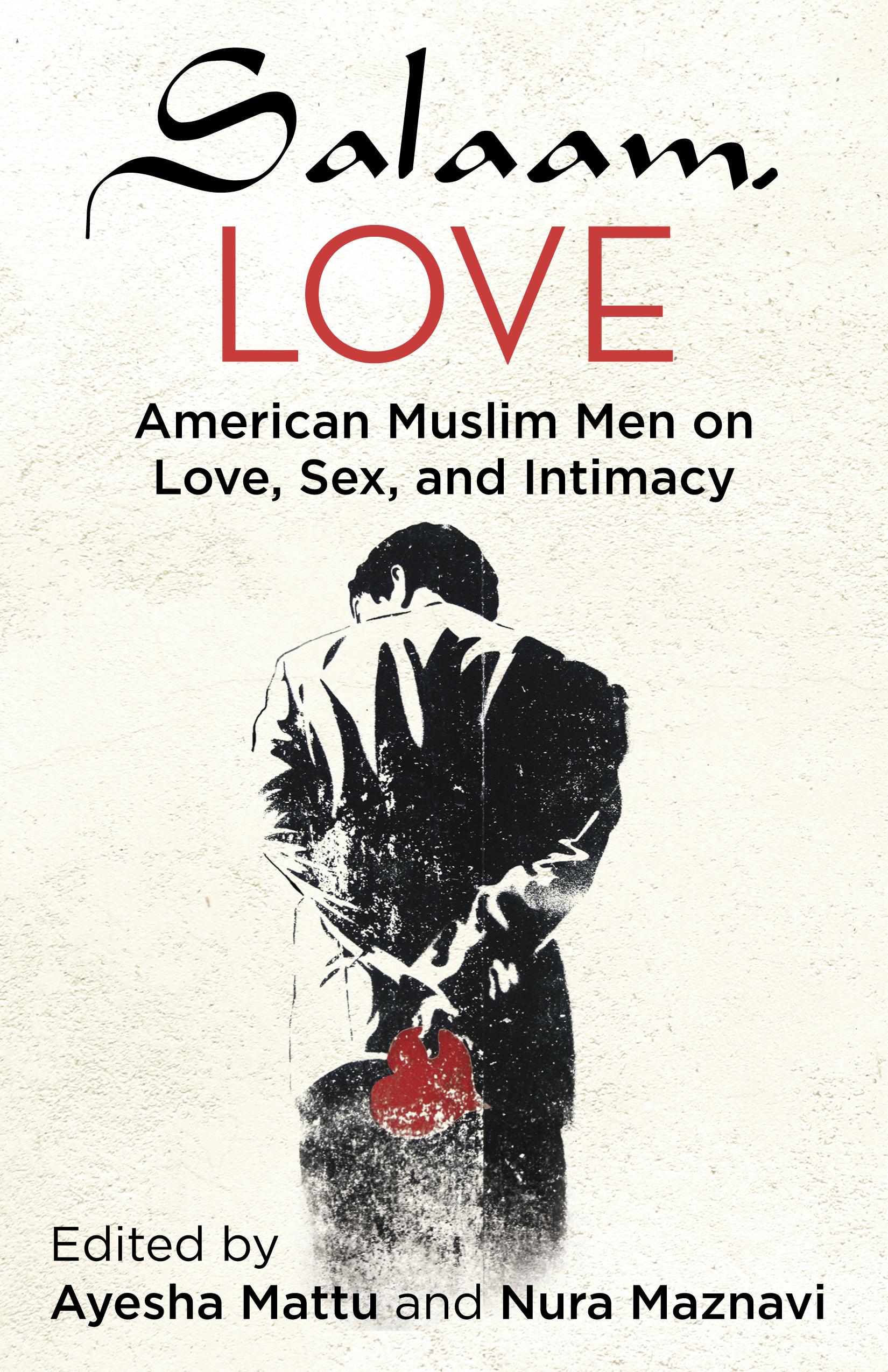

Mattu started thinking about the image of Muslim men in the US, especially after 9/11, and how it was pretty one-dimensional. “It’s basically a terrorism frame. It’s the ‘scary Muslim’ frame.” Mattu’s trying to change that with her new book called "Salaam, Love: American Muslim Men on Love, Sex, and Intimacy.”

The collection of stories range from candid essays on marriage to quirky stories about the awkwardness of asking a girl out on a date. Mohammed Shamma, a software developer in Berkeley, heard about the call for stories from his wife. He writes about trying to reconcile the Islamic belief of chastity until marriage, with the raging hormones of an adolescent boy. That duality came to a head when he was 11, during an innocent game of spin the bottle.

The collection of stories range from candid essays on marriage to quirky stories about the awkwardness of asking a girl out on a date. Mohammed Shamma, a software developer in Berkeley, heard about the call for stories from his wife. He writes about trying to reconcile the Islamic belief of chastity until marriage, with the raging hormones of an adolescent boy. That duality came to a head when he was 11, during an innocent game of spin the bottle.

“There was about four or five of us,” Shamma says. “I was the only Muslim kid. It was the first time I ever kissed a girl. But my mom found out and I got the silent treatment for several days. I knew I had to make up for it with a lot of prayer at home.”

Shamma is first-generation Egyptian American. He says he felt guilty about kissing a girl. His mom said it was a sin, but that didn’t mean he would stop. "I had to balance this world where I just wanted to be another American boy. And she wanted me to be this model Muslim boy," he says.

Shamma hopes his story will help counter the negative image of Muslims here, especially Muslims with Middle Eastern-sounding names.

“Not only does having a name like Mohammed make me get stopped at TSA, having a son whose name is Karim who gets stopped when he’s eight months old, because he’s on a list," he says. "That to me is something that needs to change. I don’t need to show my eight month old to passport control to say, ‘Look, you don’t need to be worried about this boy.’”

Shamma says personal stories like his can show Muslims in a different light and chip away at stereotypes. “If we’re willing to talk about love, we’re making that step towards that mutual agreement that, ‘Hey, we’re really the same person.’”

It's not just first-generation Muslims that deal with stigma, or the complications that come with love. Stephen Leeper in Oakland also contributed to the book. He's black and was raised Muslim, which brought its own challenges.

“Because the oppression is doubled — of being black and being a Muslim,” Leeper explains.

In his story, Leeper writes about how it was taboo to share his feelings with his family, and even some of his ex-girlfriends.

“I was told that I was weak and I was womanly and that I had too many emotions," he says.

Now, Leeper is happily married and living in Oakland.

“Telling the story in the detail that I tell it, with the amount of vulnerability that I tell it, it helps give permission to young African American Muslims, and just young African American men, to feel safe to tell their story,” he says.

Editor Mattu says she just opened the door and hundreds of essays from across the country poured in. Muslim Americans are the most racially diverse religious group in the US and Mattu says this diversity is reflected in these love stories.