A Pakistani cartoonist tries to keep up his craft in the face of rising restrictions

Political cartoons are by definition political. They're made up of pictures and captions that convey a point of view. That's the whole point.

So imagine that you're a professional political cartoonist. You've been plying your craft for nearly 25 years. But now you're being intimidated and told not to draw any person who can be identified in real life. You're also told you can't make any cartoons that criticize attacks by religious extremists, some of which have killed your colleagues and fellow journalists. Nor can you criticize your country's military for how they respond to those attacks.

And these aren't polite requests. They're threats.

That's reality for Sabir Nazar, a political cartoonist for The Express Tribune in Pakistan.

Over his career, Nazar has cartooned for a number of Pakistani publications, from The Friday Times, Pakistan's first independent newspaper, to Dawn and Pakistan Today. What distinguishes them all is that they're English language newspapers and they're liberal. The Express Tribune, for example, was founded in 2010 precisely to pursue stories that the more conservative Urdu-language press was not covering, like terrorism, religious extremism, even homosexuality.

Another common thread is that the publications embrace the political cartoon as a form of journalism. Political cartoons are relatively new to Pakistan, introduced during the time of the British Raj.

But Nazar says the political climate in Pakistan has changed dramatically. "It's really really difficult to make cartoons on issues like extremism or militancy or even about the judiciary or the army. So there's a very limited space to work at this moment in Pakistan."

Nazar says the political and security climate for cartoonists and journalists in Pakistan is possibly the worst he's experienced over his long career.

In January, men armed with pistols and silencers killed three of Nazar's Express Tribune TV colleagues in Karachi. The Pakistani Taliban claimed responsibility.

In March, Nazar came to Washington for a fellowship at the National Endowment for Democracy.He says, in retrospect, the timing was a blessing.

"A few months after I came to Washington, the attack on journalists started. And my paper [The Express Tribune] was attacked six times over a three- or four-month period.

After the attacks, the editor of The Express Tribune changed the paper's policy:

Henceforth, no criticism of militant groups or religious parties. No criticism of terrorist attacks. No criticism of the Pakistani army.

And don't even think about commenting on Pakistan's wide-ranging blasphemy law, something militants use to justify their attacks.

Nazar totally understands why his editor buckled under the pressure and the violence. But he won't change what he draws.

"I don't believe in self-censorship because that restricts your space even more," Nazar says. "So I make whatever I feel like and I would leave it to the editor if he feels it's not publishable. But I'm not going to reject any idea because, you know, it looks dangerous or anything to me."

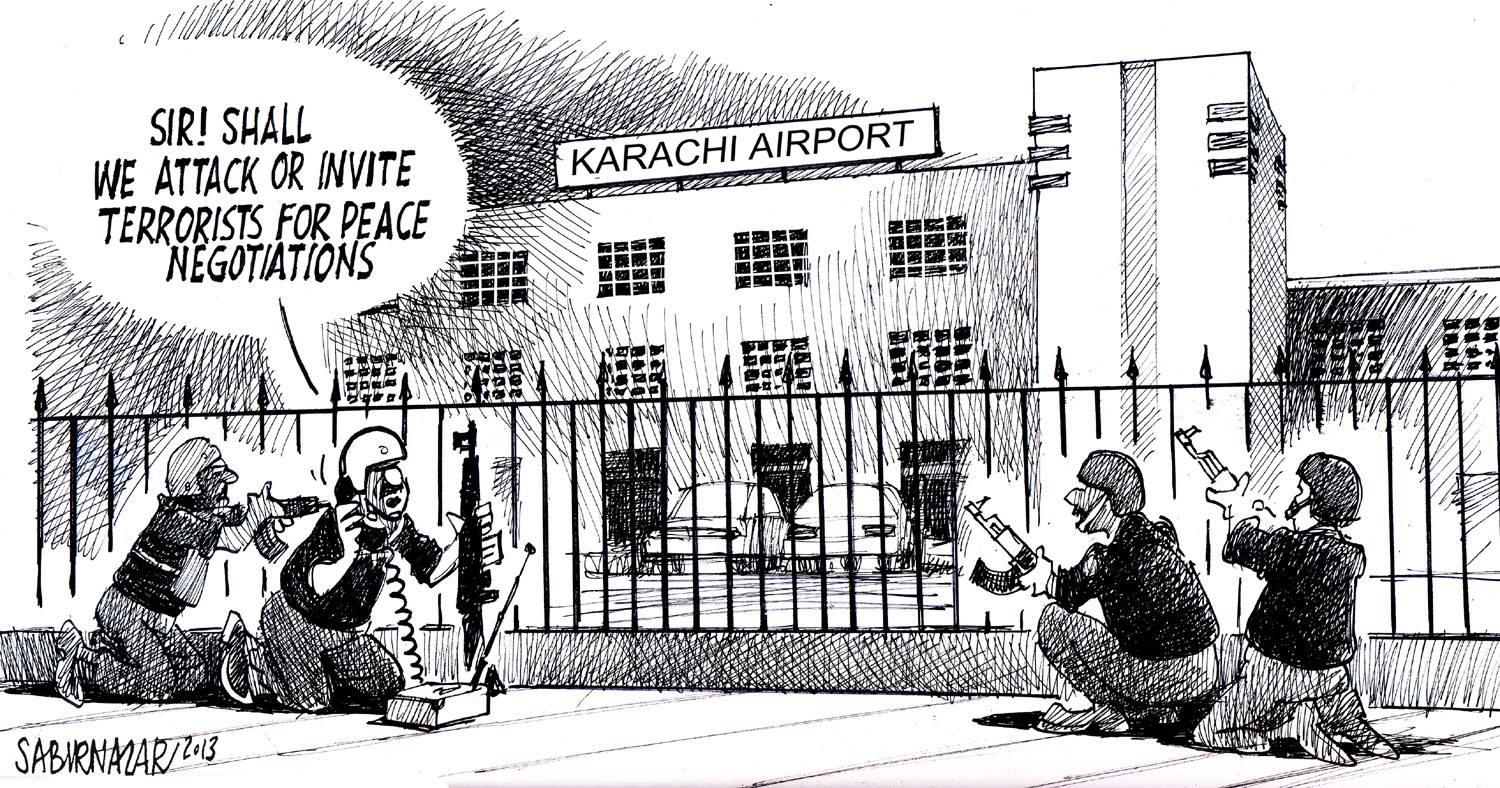

So a lot of his cartoons are rejected. But in a funny twist recently, Nazar was able to resurrect a rejected 2013 cartoon.

It was about a savage attack by extremists in June of that year on a hospital complex in Baluchistan. Militants had taken doctors, nurses and patients hostage. One suicide bomber waited for women to come in for medical treatment and then blew himself up. Nazar's cartoon showed Pakistani security forces outside the medical center wondering if they should attack the militants or wait to negotiate with the terrorists. It was a swipe at Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif who had been pushing for negotiating with the Pakistani Taliban.

Then, a few weeks ago, after the dramatic attacks on Karachi's airport, Nazar resubmitted.

The only change: the hospital was relabeled the Karachi airport. The cartoon was accepted. Nazar made sure to remind his editors that they had rejected the cartoon a year earlier.

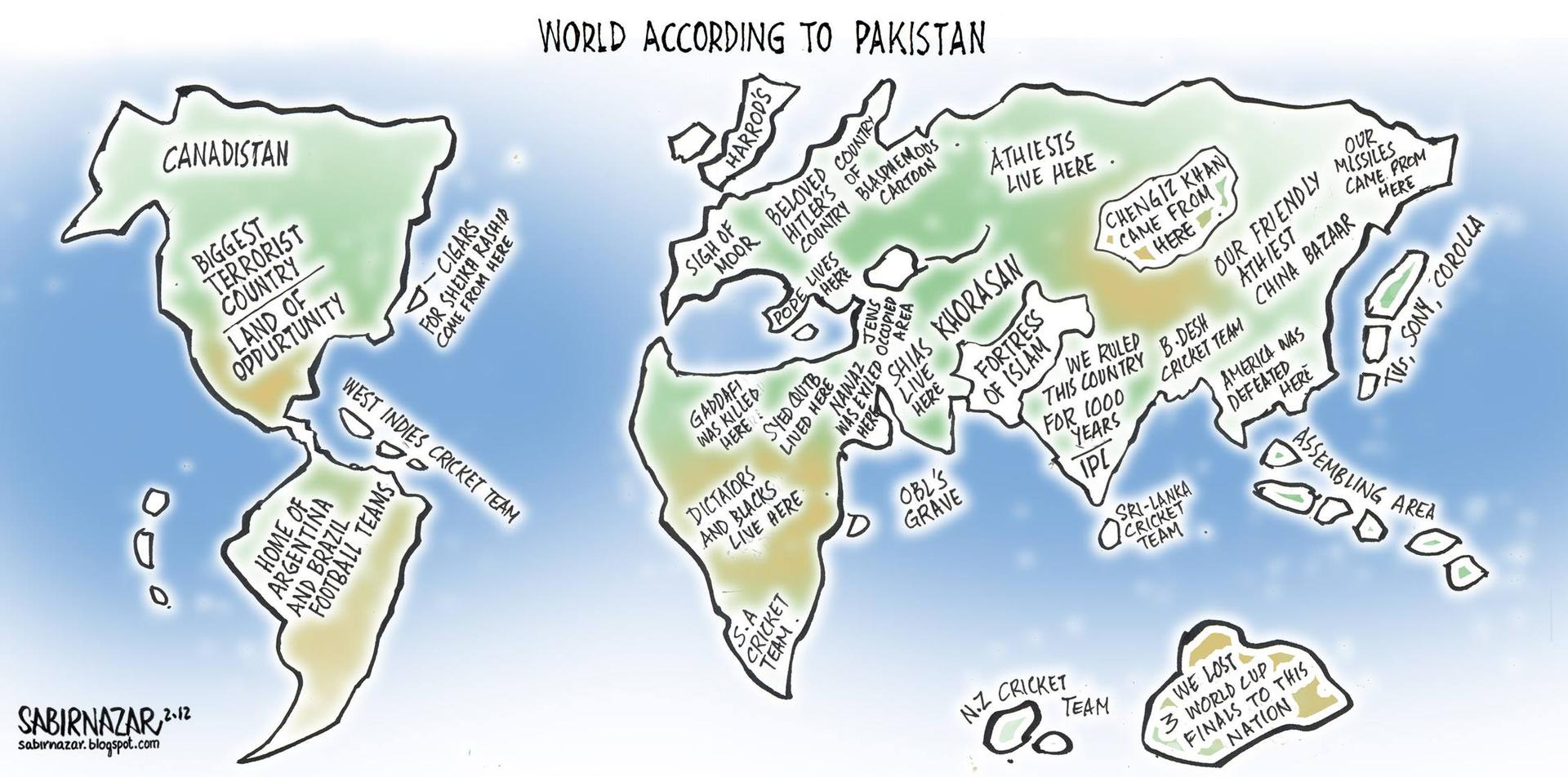

Nazar is impatient with his countrymen's tendency to tip-toe around the issue of religious extremism. He says Pakistanis have deluded themselves.

"A lot of people in Pakistan believe it's a small minority that's extremist, who are actually doing this. I once wrote a satirical column and I said, 'Well, yes, it's a small minority. The majority is peaceful and moderate, but the most popular name in Pakistan is Osama.'"

Nazar says over the past 10 or 15 years he's seen the cultural space in Pakistan narrow.

"Kite flying is banned in Lahore. If you remember that's what they did in Kabul. So I see lots of similarities with that."

Roadside billboards in Pakistan are often covered with black paint. Dancing and certain types of music are banned on college campuses. In his hometown of Peshawar, Nazar used to sit outside and draw. Now he can no longer do that because it's considered un-Islamic.

Nazar feels like the militants' assault on culture in Pakistan is partly an assault on the visual arts. Some Muslims believe that the Koran prohibits the drawing by hand of people and animals. Statues, paintings and cartoons are therefore targets of religious extremists. Nazar wants to help restore the visual arts in Pakistan, precisely because they have the ability to transcend religion, class and ethnicity.

He's using his fellowship to go through the more than 5,000 cartoons he's drawn over the last quarter century. The result will be a cartoon history of the last 25 years in Pakistan. Nazar's fellowship in Washington ends in August. He's not sure what he'll do next.

If the situation in Pakistan remains dangerous for cartoonists and journalists, he may stay away a bit longer.

Political cartoons are by definition political. They're made up of pictures and captions that convey a point of view. That's the whole point.

So imagine that you're a professional political cartoonist. You've been plying your craft for nearly 25 years. But now you're being intimidated and told not to draw any person who can be identified in real life. You're also told you can't make any cartoons that criticize attacks by religious extremists, some of which have killed your colleagues and fellow journalists. Nor can you criticize your country's military for how they respond to those attacks.

And these aren't polite requests. They're threats.

That's reality for Sabir Nazar, a political cartoonist for The Express Tribune in Pakistan.

Over his career, Nazar has cartooned for a number of Pakistani publications, from The Friday Times, Pakistan's first independent newspaper, to Dawn and Pakistan Today. What distinguishes them all is that they're English language newspapers and they're liberal. The Express Tribune, for example, was founded in 2010 precisely to pursue stories that the more conservative Urdu-language press was not covering, like terrorism, religious extremism, even homosexuality.

Another common thread is that the publications embrace the political cartoon as a form of journalism. Political cartoons are relatively new to Pakistan, introduced during the time of the British Raj.

But Nazar says the political climate in Pakistan has changed dramatically. "It's really really difficult to make cartoons on issues like extremism or militancy or even about the judiciary or the army. So there's a very limited space to work at this moment in Pakistan."

Nazar says the political and security climate for cartoonists and journalists in Pakistan is possibly the worst he's experienced over his long career.

In January, men armed with pistols and silencers killed three of Nazar's Express Tribune TV colleagues in Karachi. The Pakistani Taliban claimed responsibility.

In March, Nazar came to Washington for a fellowship at the National Endowment for Democracy.He says, in retrospect, the timing was a blessing.

"A few months after I came to Washington, the attack on journalists started. And my paper [The Express Tribune] was attacked six times over a three- or four-month period.

After the attacks, the editor of The Express Tribune changed the paper's policy:

Henceforth, no criticism of militant groups or religious parties. No criticism of terrorist attacks. No criticism of the Pakistani army.

And don't even think about commenting on Pakistan's wide-ranging blasphemy law, something militants use to justify their attacks.

Nazar totally understands why his editor buckled under the pressure and the violence. But he won't change what he draws.

"I don't believe in self-censorship because that restricts your space even more," Nazar says. "So I make whatever I feel like and I would leave it to the editor if he feels it's not publishable. But I'm not going to reject any idea because, you know, it looks dangerous or anything to me."

So a lot of his cartoons are rejected. But in a funny twist recently, Nazar was able to resurrect a rejected 2013 cartoon.

It was about a savage attack by extremists in June of that year on a hospital complex in Baluchistan. Militants had taken doctors, nurses and patients hostage. One suicide bomber waited for women to come in for medical treatment and then blew himself up. Nazar's cartoon showed Pakistani security forces outside the medical center wondering if they should attack the militants or wait to negotiate with the terrorists. It was a swipe at Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif who had been pushing for negotiating with the Pakistani Taliban.

Then, a few weeks ago, after the dramatic attacks on Karachi's airport, Nazar resubmitted.

The only change: the hospital was relabeled the Karachi airport. The cartoon was accepted. Nazar made sure to remind his editors that they had rejected the cartoon a year earlier.

Nazar is impatient with his countrymen's tendency to tip-toe around the issue of religious extremism. He says Pakistanis have deluded themselves.

"A lot of people in Pakistan believe it's a small minority that's extremist, who are actually doing this. I once wrote a satirical column and I said, 'Well, yes, it's a small minority. The majority is peaceful and moderate, but the most popular name in Pakistan is Osama.'"

Nazar says over the past 10 or 15 years he's seen the cultural space in Pakistan narrow.

"Kite flying is banned in Lahore. If you remember that's what they did in Kabul. So I see lots of similarities with that."

Roadside billboards in Pakistan are often covered with black paint. Dancing and certain types of music are banned on college campuses. In his hometown of Peshawar, Nazar used to sit outside and draw. Now he can no longer do that because it's considered un-Islamic.

Nazar feels like the militants' assault on culture in Pakistan is partly an assault on the visual arts. Some Muslims believe that the Koran prohibits the drawing by hand of people and animals. Statues, paintings and cartoons are therefore targets of religious extremists. Nazar wants to help restore the visual arts in Pakistan, precisely because they have the ability to transcend religion, class and ethnicity.

He's using his fellowship to go through the more than 5,000 cartoons he's drawn over the last quarter century. The result will be a cartoon history of the last 25 years in Pakistan. Nazar's fellowship in Washington ends in August. He's not sure what he'll do next.

If the situation in Pakistan remains dangerous for cartoonists and journalists, he may stay away a bit longer.