How Myanmar’s government is making violence between Muslims and Buddhists worse

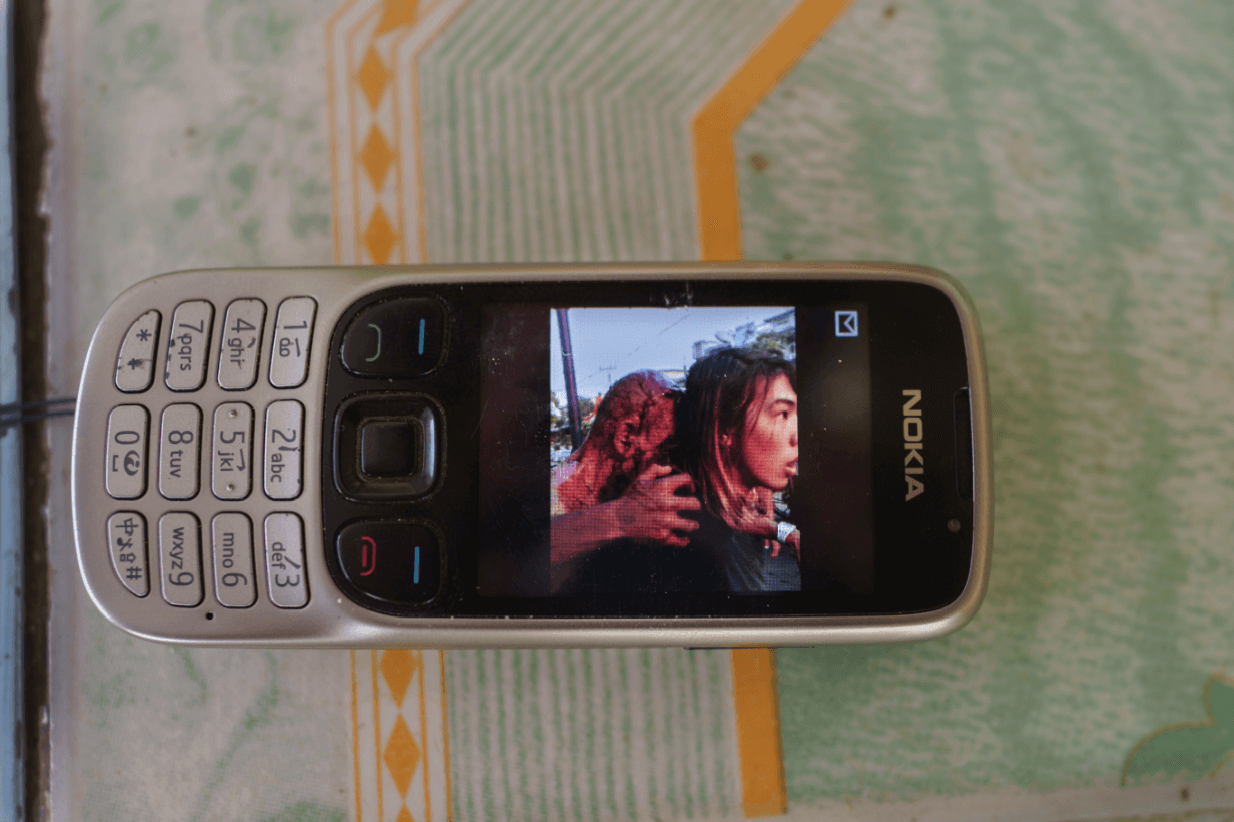

A photo on a Buddhist monk’s phone shows the monk fatally injured after a dispute in a gold shop in Meikhtila’s main market on March 21st, 2013. The incident triggered riots that cost 40 lives and eventually spread across Myanmar. (Ruben Salgado Escudero/GlobalPost)

MEIKHTILA, Myanmar — “For three days,” Khine recalls, “our town was hell.”

As the 32-year-old waitress tells it, the nightmare began with masked men waving Buddhist banners. Then came vigilantes, with torches and blades, butchering families and setting neighborhoods alight.

When the smoke cleared, Khine’s once-sleepy town was a disaster zone. Homes were reduced to cinders. Shops were smashed to rubble. And then there were the killings: 44 lives lost, many in gruesome ways.

Among the dead: Khine’s father, murdered by unknown killers. So were her half-brother and his two young children — all three hacked up by machetes, doused in gasoline and burned alive.

“It could only be called hell,” she said.

The killing in Meikhtila in March last year unleashed violence across Myanmar, in scenes reminiscent of Rwanda in 1994 but on a far smaller scale.

Following Meikhtila’s carnage, deadly riots spread across the country and left scores dead and thousands wounded. It has been a horrific development for a country enjoying its first years of relative freedom, after five decades of totalitarian rule.

Here in Meikhtila, the situation remains tense. The killing may have stopped, but survivors’ lives remain in limbo. And shockingly, the local authorities appear to be stoking the embers of conflict rather than calming the fury and repairing relations between Buddhists and Muslims.

Government complicity in the suffering isn’t unique to Meikhtila. In coastal Rakhine State, where Muslims have been purged into bleak camps, the government has even shut down life-saving Doctors Without Borders clinics that tend to besieged Muslims.

Insult to injury

One year on, many of the families who fled the killing are huddled in temporary camps divided by faith. Roughly 4,000 people live in makeshift shelters — a few monasteries for Buddhists, a sports stadium for Muslims — and await permission to return and rebuild.

They are refugees in their own town.

There are many men like Win Myint, a Muslim father crammed into an allotted 8-by-10-foot space at a stadium with his wife and three children. They share the small building with nearly 900 others.

He is desperate to return to his home district and rebuild in the rubble where his home once stood. But, as if fleeing for his life from masked vigilantes wasn’t punishing enough, Win Myint’s purgatory is prolonged by the city government.

More from GlobalPost: Myanmar Emerges

Interviews with multiple residents reveal that local authorities demand a “rebuilding permit” worth $300 to $500 from families who’ve lost their homes. In Myanmar, this amounts to between 25 and 40 percent of the average earner’s annual wages, according to United Nations stats on per capita GDP.

It is a staggering fee. In the US, the equivalent price (based on per capita GDP) would be $13,000 to $22,000.

But those able to scrape together the payment are rebuilding and trying to move on from the horror that erupted with such suddenness and savagery. Though Muslims bore the brunt of the violence — as in most of Myanmar, they are vastly outnumbered — the wave of violence also swept up the lives of Buddhists and even Christians.

Ground zero

Before March 2013, Meikhtila was regarded as just another small town in the dusty central plains.

One year later, the town’s name has become a byword for religious bloodshed.

Before the Meikhtila incident, organized anti-Muslim violence was largely contained to Myanmar’s west coast, in a state called Rakhine, home to historical enmity between Buddhists and the nation’s largest Muslim population.

But Meikhtila showed the nation that the hatred could ignite a firestorm anywhere.

The town’s violence began on March 20, 2013, with a petty quarrel in a Muslim-owned gold shop. Word of a perceived slight against a Buddhist customer spread. Within hours, a Buddhist mob had destroyed the store. In retaliation, a gang of Muslim men brutally murdered a monk that same day.

This unleashed a wave of Buddhist vs. Muslim bloodletting. Many Muslims were ousted from their homes. The lucky were able to flee. The unlucky were chopped up on the streets. Arson sprees reduced whole neighborhoods to ash.

From Meikhtila, the riots spread across the nation in fits and starts. Anti-Muslim mob killings sporadically erupted in the hilly north, the lush south and points in between.

The known death toll has topped 250 in two years. The division is so dire that even US President Barack Obama recently warned that “Myanmar won’t succeed if the Muslim population is oppressed.”

It wasn’t always so divided, Khine said. (Her name has been altered to protect her from future retribution.)

As in most of Myanmar, Meikhtila’s dominant faith is Buddhism, which places revered monks near the top of the social hierarchy and inspires intense devotion among followers.

Islam has far fewer followers. But Khine has a foot in each world. “I’m a Buddhist,” she said. Her slain relatives, however, were Muslim.

In Meikhtila — as in Yangon, Myanmar’s largest city — Buddhists and Muslims will part ways to pray but come together in neighborhoods and shops.

What forces proved powerful enough to tear them apart?

Three numbers, said Khine. 9-6-9.

Gospel of conflict

The 969 movement is an ultra-nationalist faction led by monks. Its gospel is a twisted call to arms that forewarns of Muslim takeover plots and urges Buddhists to band together and resist by boycotting Muslim merchants.

Its name is an allusion to Buddhist numerology. Its de facto leader is Wirathu, a controversial monk who lives in the nearby city of Mandalay.

His gospel is flecked with disdain for Islam. In a 2013 GlobalPost interview, he said Muslims are “like the African carp. They breed quickly and they are very violent and they eat their own kind.”

Wirathu’s adherents urge Buddhists to mark their turf with rainbow-colored stickers bearing the 969 logo. In some districts in Myanmar, these stickers are more common than the national flag.

"When I see the 969 sticker, I shudder," Khine said. "Some people don't understand what that 969 represents. No one has ever apologized to me for what happened."

During the riots, downtown Meikhtila was a no-go zone. Today, it is bustling. Trucks hauling massive teak logs whip up clouds of dust on the main drag. Townsfolk shout greetings as they pass. A sense of normalcy has returned.

But the zone where most of the killing occurred, a ward called Mingalar Zayyone, remains devastated. A prominent local school is half-collapsed. Nearby, there is the blackened shell of a burned-out school bus.

This is where more than 20 children and teachers were burned alive inside the school walls.

It is an eerie place. And it is now under 969 control.

Kathala, a monk from a nearby monastery, is among the neighborhood 969 campaigners. Having studied the Koran to discern why others follow Islam, he has since declared the scripture flawed.

The 969 movement is sensitive to its reputation for stoking apartheid-style religious division, and Kathala insists he wishes no harm upon Muslims. “My monastery helped many people [during the riots], including Muslims,” he said. “We had at least four truckloads of people who are Muslim and I allowed them to take shelter here.”

“The 969 movement just follows Buddhist scripture,” he said. He turned to a driver hired to tour GlobalPost through the ruins, and asked, “Don’t you agree?” The driver tugged at his shirt to proudly reveal his arm, tattooed with the 969 symbol: four lions of Theravada Buddhism upholding the nation of Myanmar as a Buddhist state.

The menacing monk

U Myint Oo, 66, is among the Buddhists who lost homes in the arson spree. The savagery, waged by a wild-eyed minority, has shocked a town that he views as largely tolerant.

“I grew up with everybody on this street,” U Myint Oo said. “I’ve known them long before any of this happened. We all lived together like relatives.”

But Meikhitla is now a town of stark divisions. Khine is still reeling from those three hellish days.

She lost more than her father and relatives to the chaos. She also lost a bit of her Buddhist faith. She blames a so-called holy man — Wirathu, the loudest voice of 969— for filling her life with grief instead of peace.

“Perhaps I’m not as deeply devoted and I don’t know every single thing that was taught by the Buddha,” she said. “What I know is this monk, Wirathu, what he’s been spreading and teaching has impacted me and made me suffer.”

“He may be a monk,” Khine said. “But I am scared of him.”

Manny Maung reported from Meikhtila, Myanmar and Patrick Winn from Bangkok, Thailand.