Children struggle to survive on the streets in Kabul

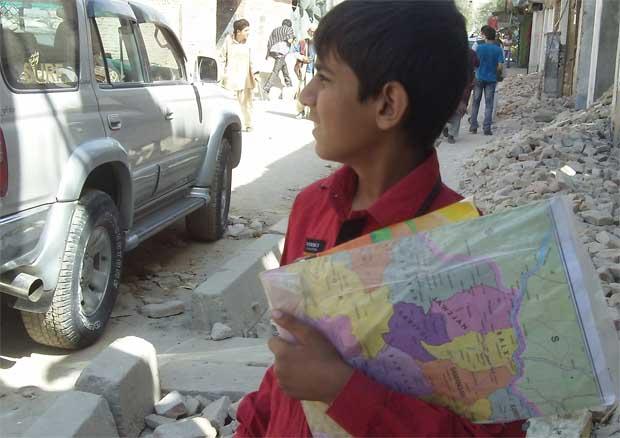

Photo of Fawad Mohammadi selling his maps in Kabul (Imag by Laura Lynch)

Story by Laura Lynch, PRI’s The World. Listen to audio above for full report.

Chicken Street in Kabul is a destination for the few foreigners who are willing to take the risk of shopping downtown, knowing both it and they are potential targets for attacks.

The road is lined with stores selling carpets, antique swords and guns from the 1800′s. It also has its own army of street kids.

Twelve year old Fawad Mohammadi is one of them. He is a young man selling old maps with a great big smile.

Fawad has been selling maps and gum on the streets of Kabul since he was five years old. Like tens of thousands of other children in Kabul, he was sent out to help support his family after his father died.

He has a friendly, open face and sparkling blue-green eyes, but the smile disappears and his eyes cloud over when he talks about the skills he has had to develop to survive.

“When I’m working on the street, I always look at what’s going on around me,” Mohammadi said. “I try to stay away from places that might be targets for bombers. And if I see someone who looks suspicious, I try to keep away from them.”

No child should have to learn such harsh lessons.

According to UNICEF, more than 30 percent of children of elementary-school age are working on the streets in Afghanistan and are often their family’s sole breadwinners.

Muhammed Yousef has been trying to help vulnerable children for more than a decade as the founder of the children’s charity Aschiana. He says since allied forces defeated the Taliban, the situation for children has improved. More than 7 million of them now go to school.

“But even now there are 4.5 million children who don’t have access to education and in their area there is no peace, no security,” Yousef said. “The children have a problem.”

The problem goes beyond working on the street. A recent study of Afghan children’s mental health by Durham University in England – the first large scale survey of its kind – found one in five children suffers from psychiatric disorders, including anxiety, depression, and post traumatic stress disorder.

Some children are forced into near slavery, early marriage or they become involved in the drug trade. In that sense, Fawad feels fortunate, but that does not mean he likes working the streets.

“I deal with a lot of different people, when I try to sell them a map,” Mohammadi said. “Sometimes they push and insult me and when they insult me, I really feel ashamed.”

Muhammed Yousef thought the lives of children would change more dramatically when foreign forces entered the country a decade ago.

“All of the people had hope, because a majority of people thought the war had ended and we would have a peaceful country,” said Yousef. “We would have access to education and our children would be protected. The children would not have to work in the street anymore, there would not be kidnapping, the government would be very strong abd we would be living in peace.”

That has not happened.

Read the rest of this story on The World website.

———————————————————-

PRI’s “The World” is a one-hour, weekday radio news magazine offering a mix of news, features, interviews, and music from around the globe. “The World” is a co-production of the BBC World Service, PRI and WGBH Boston. More about The World.