No Excuses, Just Success: The School Year Begins

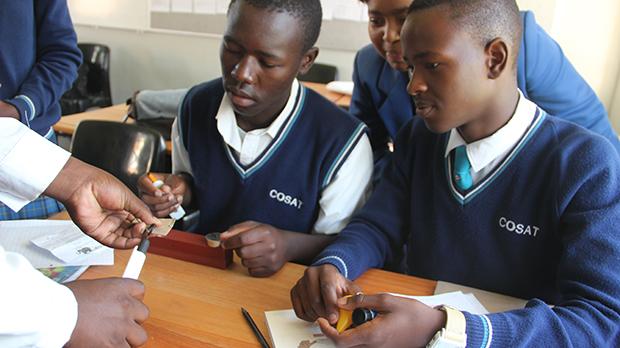

Students at Cape Town’s Center of Science and Technology learn in a science class earlier this year. (Photo by Anders Kelto.)

This story is part of a year-long series, School Year: Learning, Poverty, and Success in a South African Township.

In the middle of the day, a group of men gathers on a street corner to drink beer and call out to women passing by. Around them, metal shacks sprawl out in all directions. Garbage lines the dirt roads.

This is Khayelitsha — one of the largest and most densely populated townships in South Africa. It was built during apartheid, when the government forced black South Africans to live outside the cities.

Today, more than half a million people still live here. Crime, unemployment and abuse are rampant.

But just up the street, it’s a very different scene.

Opening Ceremony

In a large, cement courtyard, 500 students stand in matching blue sweaters, white collared shirts and blue ties. They chat and hug, and swap stories about their summer vacations. It’s the first day of school — (South Africa’s school year runs from January through December.)

The students file into an auditorium and sit in rows of folding chairs. Once everyone is seated, a teacher stands and begins singing an old South African hymn. Soon, the whole school joins in.

This school, the Centre of Science and Technology (COSAT), is a magnet high school that attracts many of Khayelitsha’s top students. Since its founding in 1999, it has been incredibly successful. During most years, every senior graduates, and 70 percent go on to college — despite the fact that most come from poor, uneducated families.

The school’s principal, Phadiela Cooper, begins the opening ceremony by paying tribute to last year’s graduates — and reminding everyone of the school’s record of success.

“We have a history of 100 percent pass rate,” she said, standing on stage.

She adds that one senior did not graduate in 2012, but that student will retake final exams in March and should restore COSAT’s perfect graduation record.

Zoliswa Lonja, from the Khayelitsha Development Forum, a civic organization that’s trying to improve the township, is also at the ceremony. “You are the chosen few,” she told the students. “You are citizens of Khayelitsha. So continue making us proud.”

Finally, it’s time for the main event: A ceremony to honor the school’s top academic achievers. Students with the best grades are called on stage to receive a handshake and a box of chocolate. As each name is called, the crowd erupts with screams and applause.

The message of the opening ceremony is clear — students here are expected to do well, no matter what stands in their way. In the words of the school motto: No excuses, just success.

Motivated Students

Sisipho, a ninth-grader with her hair pulled back in a tight ponytail, says the culture at COSAT encourages students to work hard.

“It’s nice because, at the assembly, you get recognized and you get chocolate for your hard work,” she said. But the drive to succeed is about more than chocolate and recognition.

Tandie, a 12th grader with a student government pin on her sweater and an endearing gap between her front teeth, says most of the kids here live in shacks that are falling apart, with no running water and no toilets. She says the conditions in her neighborhood are awful.

“You wouldn’t believe it, if you could see it,” she said.

Tandie says she wants to do well in school so she can get a good job and buy her family a “proper house.” Being at a school like COSAT means she’ll have that opportunity.

But it also means pressure. Tandie says her mother constantly mentions how she is counting on her to build them a better life. Like many students here, Tandie says she is terrified of failure.

“Your family’s future depends on you,” she said. “When you make a mistake, (it) all comes crumbling down. Think of how many futures you are ruining.”

That pressure can have tragic consequences. Last year, a 10th-grade boy failed his final exams and was told he had to repeat sophomore year. Principal Phadiela Cooper says she explained to him it would just take a little longer for him to graduate.

Cooper says the boy nodded and accepted what she said. But after their conversation, he sent text messages to his brother and friends, telling them that he had failed — and that he didn’t feel like living.

“He went home and committed suicide,” Cooper said.

New Pressures

As the 2013 school year begins, the boy’s death looms over the school.

There's also a fear that the pressure on students and teachers will be even more intense this year, because the school is growing — rapidly.

The South African government, having seen COSAT’s success, has forced it to expand from 190 students to 500 in just three years.

That means more kids now have a chance to learn here, but it also means the things responsible for the school’s success are changing. The student-teacher ratio is rising. Instructors are teaching more classes and working longer hours. And, perhaps most important, the standard of admission has been lowered.

“We are getting more of the learners who are not adequately prepared,” Cooper said.

Some teachers worry these students will fail.

But what if COSAT can maintain its near-perfect graduation rate, on a much larger scale? What if it can turn even poorly prepared students into budding scientists bound for college?

If this school can continue its record of success, a lot of people will be asking how it did so — and whether this model can be replicated in poor communities elsewhere in Africa and other parts of the world.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!