Nazi version of ‘Titanic’ gaining renewed attention as anniversary approaches

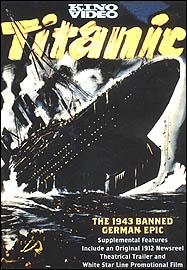

The 1943 Nazi propaganda film Titanic has drawn renewed interest as the 100th anniversary of the ocean liner’s sinking nears.

This weekend will mark 100 years since the sinking of the Titanic. There are countless events marking the anniversary, including an auction of artifacts from the ocean liner, a cruise to the ship’s final resting place in the north Atlantic, and the re-release in 3D of James Cameron’s 1997 blockbuster.

But there’s another Titanic movie that’s getting some renewed attention too. Like Cameron’s movie, this one’s simply titled “Titanic”. It features a love story and the sinking of the unsinkable ship. But there the similarities end.

This “Titanic” was a piece of Nazi propaganda, commissioned by Joseph Goebbels.

In his version of the story the ship sank as a result of British greed. The film opens in the London Stock Exchange, where the share price of Titanic’s parent company, White Star Line, is plunging. It’s no accident: the chairman of White Star, Bruce Ismay, is working to make it happen.

“And the way he’s going to do that is to suggest that the company is in trouble because of the huge expenses in building the Titanic,” said Randall Bytwerk, an expert in Nazi propaganda at Calvin College. “That’ll drive shares down. Then when the ship has set sail he’ll announce that it’s setting a world’s record pace, and that’ll drive shares up and supposedly he’ll make his fortune.”

Ismay was a real man, and he was widely criticized after Titanic’s sinking for taking one of the few seats available on a lifeboat. But in the Nazi’s telling, he’s simply an evil British plutocrat scheming to profit off the backs of everyone else.

During the film, Ismay urges the ship’s Captain Edward Smith to go faster and faster, offering him $1,000 for each hour the ship arrives ahead of schedule.

Of course there’s also a voice of reason, someone pressing Smith to follow a safer course. That’s a fictional first officer, a German by the name of Petersen who embodies all the qualities a Nazi member of the audience might find admirable.

Ian Garden, author of The Third Reich’s Celluloid War, described him as “the archetypal officer who keeps on warning the captain ‘you’re going too fast, we’ve not got enough life boats, we’re going to hit an iceberg’. And they refuse to listen to him.”

“You’d expect him to go down with the ship,” Bytwerk said, “and he almost does, but he’s saved by doing a good deed. As he’s prowling around the sinking ship he hears a small child crying who’s been left by its plutocratic mother to die to save her own skin. He rescues the young girl, dives into the water, carries her to a waiting lifeboat — where, by the way his love interest is waiting — and both he and the young girl are saved. So the hero is a German.”

“Titanic” was an incredibly expensive film for its time: the special effects were state-of-the-art. It took a long time to make. Too long, it turned out.

Work on the film began in 1940 when Germany’s military was conquering all. But by the time the film was ready for its premiere screening in Berlin, things weren’t going so well and Goebbels had second thoughts.

Bytwerk said the Nazi propaganda minister realized scenes of panic and mass death wouldn’t play well to German audiences in the spring of 1943.

“British and American bombers (were) coming over day and night, the Stalingrad defeat (was) clear to everybody. So the film just (didn’t) look propagandistically good,” he said.

The Nazi’s “Titanic” was a piece of propaganda based on a tragedy, but the film seemed only to beget further tragedies.

Look what happened to the director, Herbert Selpin.

“He was overheard one day complaining one day about the war getting in the way of the making of his film,” Garden said.

Selpin’s complaints got back to Goebbels, who demanded an apology.

“But Selpin was a very stubborn man, he refused to apologize,” Garden said. “He was put into a prison cell and the next day he was found hanged dead from his braces in that cell.”

Was it suicide, was it murder? Most think the latter. In any case, that was a single man. What happened later couldn’t be written, Garden said.

“The ship that they used to film the outside scenes on was a ship called the Cap Arcona. That ship, at the end of the war, was sunk by mistake by the Allies as it was carrying — of all people — 5000 concentration camp prisoners. And they were all killed,” Garden said.

Hitler had met his end days earlier; the remaining Nazi leaders were trying to cover up their crimes by removing people left in the camps. Some also think the Nazis disguised the ship as a troop carrier, almost inviting an attack.

“So there were far more people killed on that ship than were actually killed on the real Titanic. It’s a terribly sad story,” he added.