Magicians face rash of trickster thieves

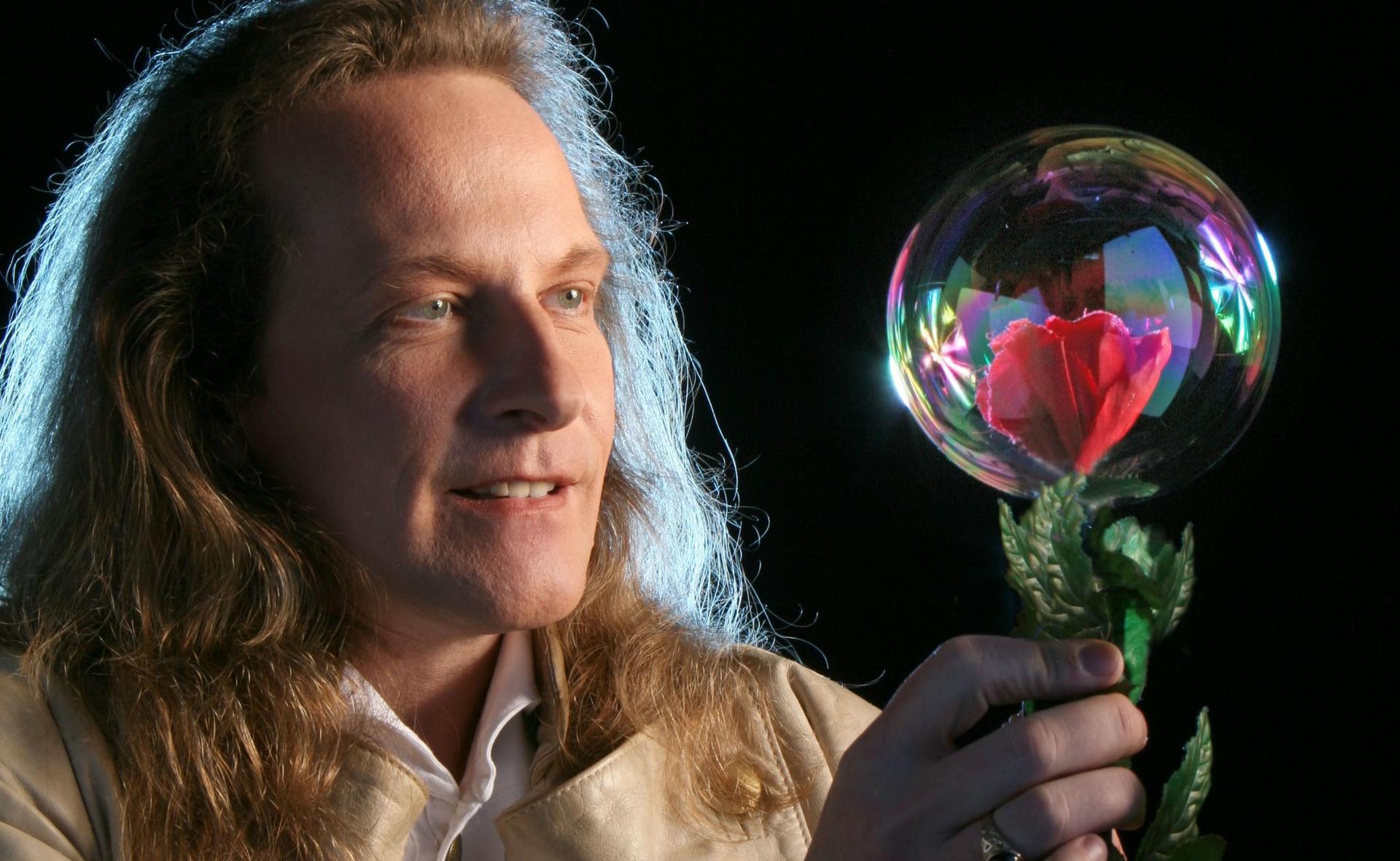

The “Master of Levitation,” Losander has found his tricks being stolen and resold on the cheap. (Photo courtesy of Losander Inc.)

Magicians have stolen each other’s secrets for as long as the art of magic has existed.

But the interconnectivity of today’s world is making it easier — and magicians can’t always rely on the law to protect them.

Jeff McBride is one of the most accomplished magicians in the world. Seeing him perform, it’s easy to fall under his spell — you half think he might actually have magical powers.

His most famous routine is an intricate series of transformations, with a variety of masks, taking the audience through the entire history of magic.

But, one day, McBride discovered he was not the only one performing this particular act.

He spotted a clip on YouTube of a Thai magician doing his entire routine on local TV — move by move — along to his music. He’d even cut and dyed his hair to copy McBride.

“It’s the most carbon copy sort of duplication I have ever seen,” McBride said. “This was the whole enchilada… It’s not just a duplication of one of my tricks, it’s not just an exact copy of one of my routines — it’s my show, my entire show.”

His fans were calling for the Thai magician’s head, but McBride, with the help of Google Translate, decided to get in touch and talk it out.

“It seemed like he was doing a tribute act like someone would do a Beatles or Pink Floyd or a Black Sabbath tribute act. I could obviously see that, so I didn’t want to slam the guy, but what he was doing wasn’t right,” he said.

This dispute ended amicably, but that is often not the case, and magicians complain that their tricks are being ripped off like never before.

“It’s a sad situation. It’s like a cancer in our business,” said magician Kevin James, who is is nicknamed “the inventor” because of his record of innovation.

Magicians argue that for young people to become interested in magic, and continue the tradition, they need to learn from the masters of the day, and need access to existing tricks. Selling tricks is also how many magicians make enough money to stay in the business.

But James has had numerous tricks copied and sold at knock-down prices on Chinese websites — using his name and branding.

“They use my advertising, they use my photos, they use my video on their websites, they use my text to sell it. They make it look like it’s my product — only a third the price,” he said.

You might well think that a magician would be protected from this — that they could sue, or that they would have some sort of recourse to the law.

But there is little they can do, says Sara Crasson, a lawyer specialising in intellectual property rights, and a magician herself. Magic tricks fall into, if not a black hole, certainly a legal grey area.

In a recent case in the Netherlands, a court ruled that tricks and illusions per se are not protectable, but that when put together into a specific sequence, as part of a magician’s routine, they effectively constitute a kind of drama, and can therefore be granted copyright protection.

It was seen as a landmark case, but it only covers magicians who, like McBride, have had their whole act, or a significant section, copied.

Beyond this, it’s effectively a kind of magical Wild West.

As magic is all about secrets, you might expect magicians’ tricks would gain protection under the principle of trade secrets — this is how Coca-Cola guards its recipe and how KFC protects the spices it uses on its chicken, for example.

But with a trade secret, the onus is on the holder to guard it and, as public performers, this poses a problem for magicians.

“If someone can watch the performance and figure out what the secret is, then that magician would lose trade secret protection,” Crasson said. “For magicians, trade secrets are a lot tougher to keep because magicians frequently do know how other magicians do their work.”

There have been some pretty brazen examples in the past — perhaps none more so than the case involving the world-famous U.S. magician Harry Kellar at the end of the 19th Century. He was so keen to work out how British magician John Nevil Maskelyne was doing his levitations, that he went to the show several times — armed with binoculars.

When that failed, he marched right up to stage at the key moment to take a peek. He still couldn’t work it out, and ended up bribing another magician at the theatre to provide him with sketches. Kellar performed this particular act around the world for years afterwards.

The modern-day version of this story is perhaps the case of German magician Losander, who is renowned for his levitations.

In the most famous part of his act, a table floats impossibly, darting around as if possessed.

The floating table is not just Losander’s signature illusion, it’s his magical legacy. His tables are on sale, marketed at professional magicians, and can cost thousands of dollars.

At least, that was, until knock-offs “popped up like mushrooms” on Chinese websites — often with dubious branding suggesting the product was endorsed by him.

“It should be handled like money,” Losander said. “If you rob a bank, you go to jail (but) if you steal somebody’s idea, they say ‘God bless you’.”

Occasionally magicians patent their tricks, but a patent puts the information out into the public domain — exactly what a magician wants to avoid.

There are practical problems too.

“Your patent is only as good as your ability to enforce it,” said Kevin James, who patented his amputated arm illusion — but found that didn’t stop the imitations.

“I went to an attorney. He said, ‘Well, OK, I need $30,000 to start with… There’s no pot at the end of the rainbow. I’m not sure if it’s something you want to pursue.'”

James decided he didn’t want to spend his whole time chasing “bottom feeders.” In fact, he is thinking about giving up the whole business of selling his tricks.

But if magicians don’t get products out to market at all, then young magicians have nothing to learn from, and this could lead to the downfall of the art in the long run, he says.

Like magicians, comedians have long complained of having their jokes stolen with impunity by rivals with no recourse under the law. They rely on a code of ethics — not the law — to regulate their industry.

And that’s the flip-side to all this, says James. Just as an interconnected world has increased the speed and ease of ripping off ideas, it has also allowed for the spread of the idea of a magicians’ code of ethics.

Arguably, this kind of voluntary self-regulation could actually foster creativity among magicians. A recent cover story in the trade magazine Magic identified South Korea as a hotbed of talented new magicians.

It’s also home to the Do Not Copy the Magic campaign — one of the most active movements against stealing tricks in the industry.

Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you. We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll help us unlock a matching gift of $67,000!