Bond movie Skyfall’s deserted island a real place — in Japan

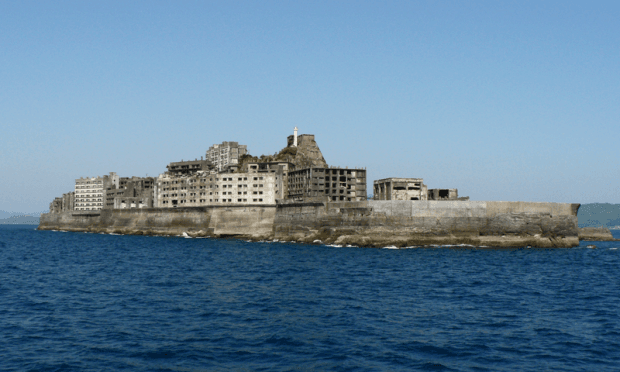

Hashima Island serves as the villain’s lair in the new James Bond film “Skyfall” (Photo by Hisagi via Wikimedia Commons.)

If you’ve seen the new James Bond film “Skyfall,” then you were probably struck by Javier Bardem’s portrayal of the villain, Raoul Silva.

He’s a bad dude, and his evil island lair seems a fitting place for him — a rotting heap of buildings sitting out in the middle of the ocean, populated with derelict buildings. It’s so creepy, that you think it can’t be real.

But here’s the thing. The island is real. And its history is even creepier than you can imagine.

The island is known as Hashima, or alternatively as Gunkanjima (“Battleship”) Island, and it sits about nine miles off the Japanese coast in the East China Sea.

In the late 1880s, coal was found on the sea floor beneath the island. In the early days, Japan’s Mitsubishi company, which was mining the coal, would ferry miners to the work site from Nagasaki.

Then, the company decided it would be easier to just build houses for the workers, and their families, on Hashima itself.

Giant, multi-story, concrete apartment blocks went up. Schools, bath houses, temples, restaurants, markets, even a graveyard, were built, all on a space the size of a football field.

“Once they reached 5,000 people or more out there, it was recognized as the most densely populated place on earth … ever,” said Thomas Nordanstad, a Swedish filmmaker.

A decade ago, Nordanstad became interested in Hashima’s history, and wanted to make a documentary about the island.

HASHIMA, Japan, 2002 documentary version from Thomas Nordanstad on Vimeo.

He and his filmmaking partner went to Japan, but found that the Japanese weren’t interested in talking about it.

“We met a lot of embarrassment. We met a lot of hushed faces, a lot of people who would turn away as soon as we started speaking about the island, almost like it was a leper colony or something,” he recalled.

Norandstad eventually found someone to take him out to the island. The short film he made follows Doutoku Sakamato, whose family moved to Hashima when he was four.

In one scene, Sakamoto returns to the apartment where he lived with his family 30 years ago.

“My mother’s decorations are still up here,” Sakamoto said.

A few seconds later, he found the marks on the walls that recorded his sister’s height through the years.

Hashima, you see, is completely abandoned. The buildings are slowly falling down, worn away by the wind and the waves.

So, what happened?

“In 1974, the coal ran out,” Nordanstad said. “And the Mistubishi Company told the people that they would have some work for them on the mainland, provided on a first come, first served basis. And that’s why people left so quickly.

“They left coffee cups on the tables, and bicycles leaning against the walls. And I think very few people had been back out there when we went there. It was practically untouched,” he said.

Nordanstad’s film follows Sakamoto as he finds a schoolhouse with the teachers’ names still written on the blackboard.

Sakamoto reflects on the people who once lived there and risked their lives in the mines below.

“It’s like the souls of the dead linger on down here,” Sakamoto said. “So many people who died, so unecessarily … but these are things I probably shouldn’t talk about.”

Nordanstad’s documentary is a decade old now, but two years ago something strange happened.

Actor Daniel Craig, who plays Bond, was in Stockholm shooting a different movie. He was staying at a hotel where one of Nordanstad’s pictures of Hashima was hanging on the wall.

Nordanstad remembers being introduced to Craig at some event.

“He leaned back with the typical kind of raised Bondian eyebrow, and I told him the story of Hashima, and he noted everything down. For a while, I thought he was going to buy the Hashima piece, but he didn’t,” Nordanstad said. “Two years later, the movie came out.”

Skyfall only features external shots of Hashima. The scenes on the island were actually shot in a studio.

That’s because Japanese officials don’t allow anyone to set foot on the island itself.

But lately, interest in Hashima as a grisly tourist site has grown. A boardwalk has been built around half the island, but that’s about as close as you can get.

Meanwhile, Doutoku Sakamoto wants the island to be recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. But South Korea objects, because the Japanese allegedly used Koreans as slave laborers on Hashima.

It’s yet another shameful chapter in the island’s history.

The place, Nordanstad says, is haunted.

“There are ghosts there for sure. And there is something not right about the place. For sure,” he said. “There is nothing pretty about it. There’s nothing beautiful about it. The whole place is just death and decay.”