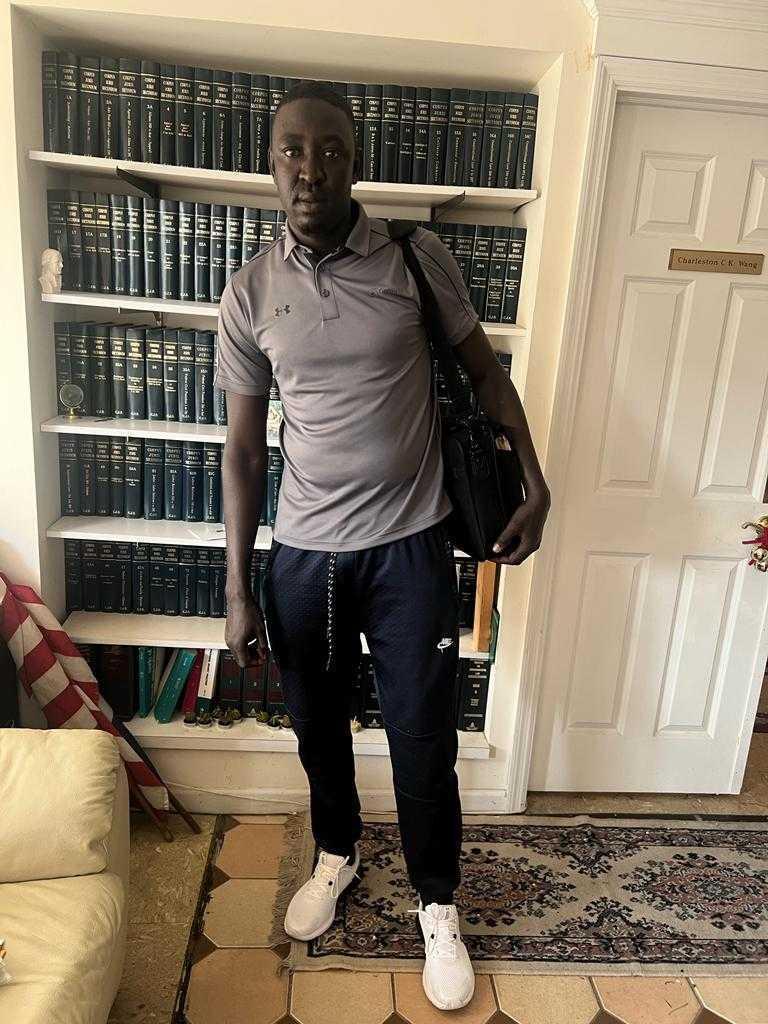

For the past six months, Oumar Ball’s house in Cincinnati, Ohio has turned into a shelter for Mauritanian migrants.

“I have almost 20 immigrants living in my place,” he said. “I offer them food, I help them apply for asylum, get an employment authorization card, learn English and find a job.”

An immigrant himself, Ball left Mauritania in 1997 and settled in Ohio, home to the largest Mauritanian community in the United States.

There are about 8,500 foreign-born Mauritanians in the US, and about half live in Ohio.

Ball said that he had never seen so many of his compatriots arriving at once.

“I decided to help people because it’s my time to pay back for all the good things this country has given to me,” he said.

Migrants from African countries still represent a very small fraction of the people crossing the US southern border. The vast majority come from Latin America and the Caribbean.

But the number of Africans apprehended at the US southern border increased by 436% in the span of one year, according to data from Customs and Border Protection obtained by The World.

It jumped from 13,403 people in the 2022 fiscal year to 58,462 in 2023.

Mauritanians are at the top of the list of African nationalities apprehended at the US-Mexico border in the 2023 fiscal year, with 15,263 people.

Senegalese follows with 13,526 people, and Angolan and Guineans are in third place, with each having more than 4,000 people apprehended.

There is a combination of factors driving more Africans to the US.

One of the biggest factors, though, is the popularization of a new route via Nicaragua that emerged a few years ago and has been promoted on social media.

The Central American nation has few visa requirements for citizens of several African countries.

“Most migrants who are now living in my house came through Nicaragua,” Ball said.

In the past, African migrants headed to the US had to fly to Brazil first and then trek through the Darien Gap, a dense stretch of jungle that separates South and Central America. Flying to Nicaragua allows people to skip that dangerous part of the journey and continue northbound by land.

For the people who make it to the US-Mexico border, the chances for admission are currently very high, according to Muzzafar Chishty, senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute.

“If you apply for asylum [in the US], you won’t get a hearing for years, and during that time, you can work legally. The chances of being removed, even if your asylum application is denied, are very low. So those are really very important pull factors.”

“If you apply for asylum [in the US], you won’t get a hearing for years, and during that time, you can work legally. The chances of being removed, even if your asylum application is denied, are very low. So those are really very important pull factors,” Chishty added.

While the US has ramped up deportation flights in recent months, Chishty said it is very challenging to deport people to Africa because the US doesn’t have deportation agreements with many African nations.

Chishty also said that US immigration authorities are allowing more migrants into the country because detention centers are at capacity.

Europe has long been a more common destination for African migrants. But immigration policies have become more restrictive in several European countries, said Camille Le Coz, associate director at the Migration Policy Institute in Europe.

“There are increased efforts from Europeans to work with different countries in Africa to prevent people from coming,” Le Coz said. “And in turn, this has made journeys more expensive and more dangerous.”

Migration from Africa to Europe is expected to remain high and even increase in 2024, as people try to reach the continent before the introduction of stricter immigration laws.

But some African migrants who can afford it might decide to take safer routes by air, Le Coz said.

Many migrants are escaping from dire situations at home. Millions of Africans have been displaced by regional armed conflicts, rising poverty and climate change.

In the case of Mauritania, many people are running away from state violence directed against Black Mauritanians, according to Abdoulaye Sow, communications director of the Mauritanian Network for Human Rights, a nonprofit organization in Cincinnati, Ohio.

In May of last year, racial tensions increased after the death of a young Black man, Oumar Diop, in police custody, and protests were aggressively shut down.

“A non-democratic regime is continuously undermining human rights for Black citizens,” Sow said.

Mauritania was one of the last nations to criminalize slavery, and the practice is still believed to persist in parts of the country.

Several Mauritanians who spoke to The World said police are persecuting them because of anti-slavery activism.

One of them is Nadzirou Tambadou, who is living in Oumar Ball’s house in Cincinnati.

He said his father was assassinated in the 1990s by an Arab-led military government when he was 7 years old. He recently started fighting for racial justice and was targeted by Arab authorities.

“I left my country because my life is in danger,” he said. “They treat Black people like slaves, and they kill you if you don’t like their system.”

Tambadou is hoping he doesn’t experience discrimination in the US.

So far, he feels optimistic, safe and accepted in his new community in Ohio.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?