Almost 7,000 families in Massachusetts are homeless and living in state emergency shelters.

That is unprecedented and expected to rise, according to state officials. Massachusetts is a “right to shelter” state. By law, homeless families are given a temporary place to live.

Earlier this year, the state emergency housing system reached its occupancy. Now, many families are being housed in unused college dorms and hotels.

In western Massachusetts, about 800 families live in shelters; dozens recently migrated to the US from Haiti, Venezuela and other countries. At the start of October, in West Springfield, 55 families were being temporarily housed, including in two hotels.

The housing situation is extreme, but normalcy is setting in — getting kids to and from school.

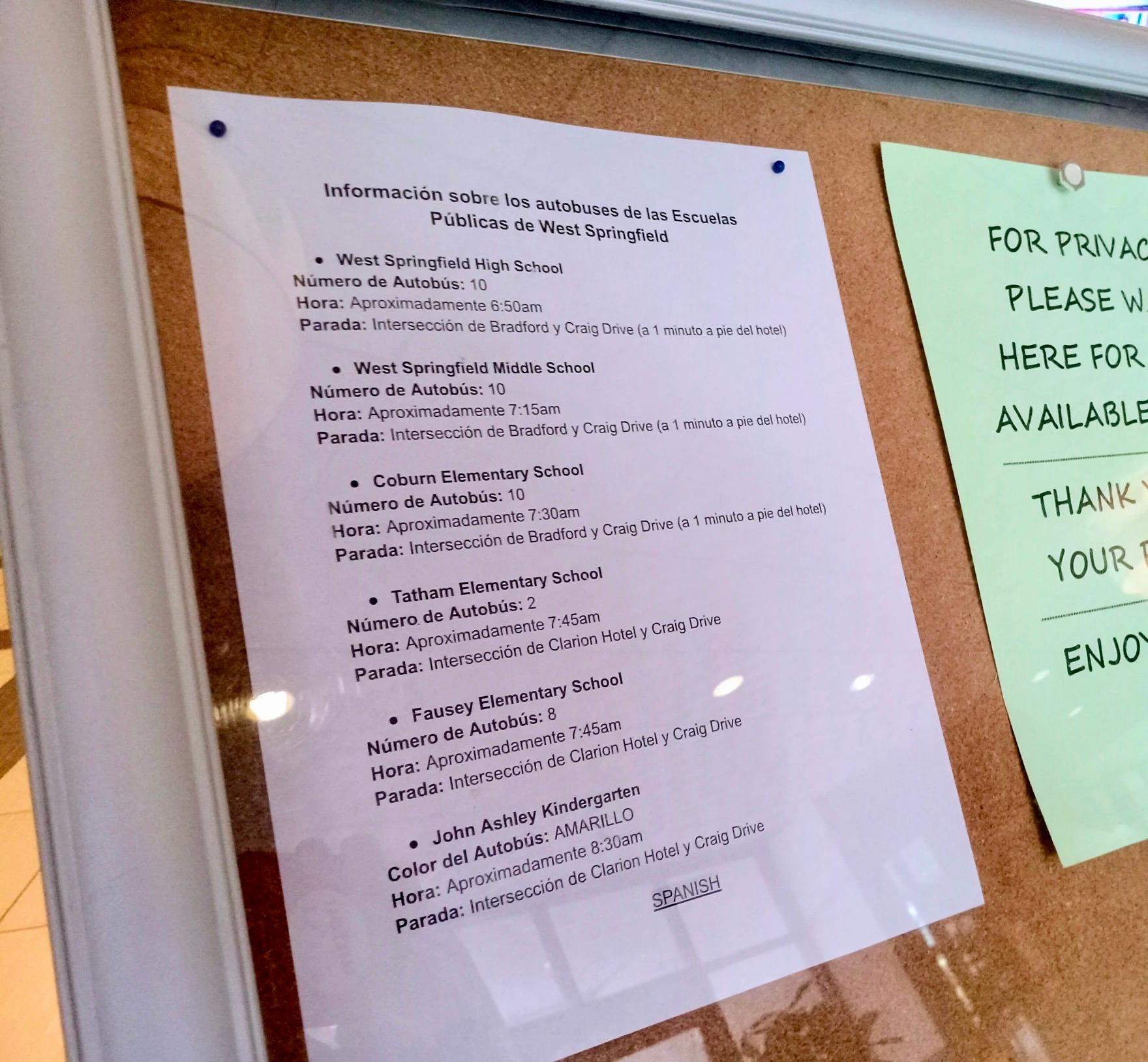

Several buses take children to and from school to the hotels where they live. On a recent afternoon, parents stood outside the lobby, catching up with each other.

Morad Majjad, a West Springfield Public Schools family liaison, was in the mix. Majjad speaks five languages and, in this crisis, his colleagues see him sort of as a rock star. He shows up at shelters and can easily communicate with families, connecting them to school resources.

Parents were glad to see him, and some were relieved to have their questions answered in their native language. A few children ran to catch up with Majjad.

“How you doing?” one asked as Majjad walked into the hotel lobby. He took a few minutes to ask them how classes were going.

With the new school year underway, Majjad encouraged parents to come to a meet-the-teacher night. He passed out transportation vouchers to get them to school that evening.

More families coming, more students enrolled

Majjad is among a group of liaisons and social workers in the district who work with homeless families. School officials expect more will be arriving.

“At the end of 2022, our numbers were about 40 [homeless] students. And then when December rolled around, our numbers got to 99 students,” said Jackie Willemain, the district’s homeless liaison and a licensed social worker.

At the start of the 2023-2024 school year, 140 students without housing attended school, Willemain said. About 60% arrived in the US from another country.

In Massachusetts and elsewhere, the increase in homelessness stems from a post-pandemic rise in the cost of housing and a surge of people seeking asylum because of geopolitical crises around the world.

“It is a constant flow in,” Willemain said.

In West Springfield, one of the area social services agencies, CHD, is a resource for families. Willemain said she works closely with them.

The kids

By the time the children are enrolled in school, she said, they’ve been through a lot. They’ve left family and friends behind; some have witnessed violence and — in general — experienced trauma. Yet Willemain said most are excited to start over.

“The children are so eager, and just beautiful, wonderful learners,” she said.

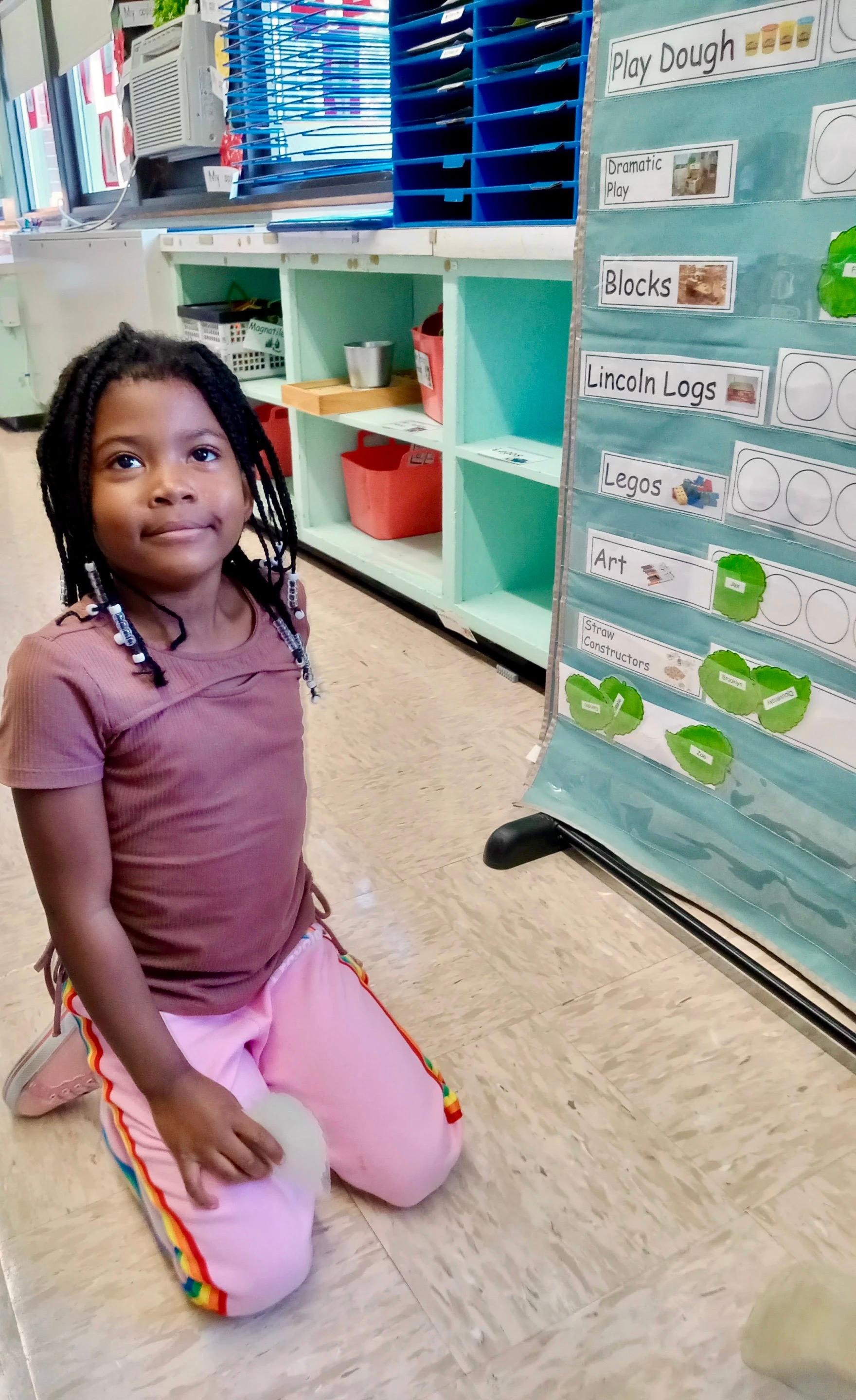

Among them is second grader Frantchierna Valcius, who said she loves school. She also likes to be called Sarah, she said. That’s her middle name.

“When I come [to school], I see my friends. I eat, and I play and I love to make activities, too,” she said.

Those activities come from her teachers, and she brings some home to work on after school. She’s lived at a hotel with her parents and older sister since March 2023.

Frantchierna, her sister Micherna, and their father sit in one of the hotel’s ballrooms, with mirrors paneled on the walls, stacks of chairs, and band instruments students leave here instead of in their rooms.

Micherna is in 11th grade and said she’s getting very good grades.

“I was thinking [I’d like to] study nursing,” she said. “But, for real, I want to be a surgeon because they make a lot of money, and it’s important for society.”

The girls’ father, Frantzset Valcius, speaking in French, said it’s been a harrowing journey trying to make a better life.

Their family first left Haiti after the devastating 2010 earthquake. They moved to Brazil, and he and his wife ran a cleaning business. When anti-immigrant sentiment became to much, Valcius said his wife and children flew to Mexico. He traveled by bus and on foot.

They worked their way up to Florida, then Massachusetts late last winter, seeking to stay in the US.

Valcius desperately wants his children to benefit from living in the States, he said. He’s been waiting for a work visa so he can start a job and find an apartment.

Right now, home is their hotel room without a kitchen. Micherna said she sometimes sits in the hotel hallway to do her homework and get some privacy.

West Springfield, an international school district

A 2020 US State Department data analysis shows West Springfield was fourth in the country per capita for refugee resettlements.

“The families that come to our community who are settling here in West Springfield, some of them are second generation,” said Sharlene DeSteph, director of the district’s English Language Learner program.

Among the top languages, DeSteph said, are Arabic, Spanish, Turkish, Russian, Ukrainian and Nepali. Students also speak Pashtu, Vietnamese and more.

Before the recent homeless emergency, DeSteph said there was an advance notice from social service agencies that families were coming and students would enroll in the district.

“This is the first time that we’ve had homeless families coming in that have been English-learner families,” DeSteph said, “fleeing horrific situations.”

At times, families show up at the school offices, DeSteph said, asking for support.

“Sometimes we hear of them through other families, and we find out that they’ve been here for a month and they were waiting to see if school was going to reach out to them,” she said.

Crowded classrooms and no end in sight

English language learning teachers have been added to classes, but — overall — teachers are managing overcrowded classrooms, said West Springfield Public Schools Superintendent Stefania Raschilla.

“It’s really challenging for some students who have traveled, you know, a long time from country to country to country, and now they’re here [and] sometimes they may need multiple services,” Raschilla said.

Massachusetts is providing districts with emergency aid, including $104 per student per day. Additional funds have been made available to transport students from emergency shelters to schools, including when the shelter is located in another community.

When superintendents met earlier this year with Massachusetts Commissioner of Education Jeffrey Riley, Raschilla said she inquired if the state would lift twice-yearly literacy testing requirements for students arriving from other countries.

“Wouldn’t we be better off waiting a bit before we say, ‘OK, we’re going to assess your English?'” Raschilla said.

“We know that [they] don’t speak English. [They] just got here.”

Massachusetts education officials said the screenings identify which students might have literacy-based challenges.

A spokesperson in Gov. Maura Healey’s education office said the state screens for English-language barriers and learning challenges like dyslexia.

At that meeting with Riley, Raschilla said the commissioner alerted superintendents about the coming influx of homeless students. He told them he didn’t see an end in sight, she recalled.

“I feel for these families,” Raschilla said. “My grandmother came over [from Italy] with my mother on the boat and my mother was thrown into school in Springfield. She couldn’t speak English. She just remembers crying and crying.”

When you come here with nothing, Raschilla said, school is a way out of that. Families left wherever they came from because it wasn’t good, she said, and they want their children to have opportunities.

An earlier version of this was published on NEPM.