The parallels were striking — and surely not coincidental.

Exactly 50 years and a day after being taken completely off guard by a coordinated military attack by its neighbors — Egypt and Syria — Israel was again caught by surprise.

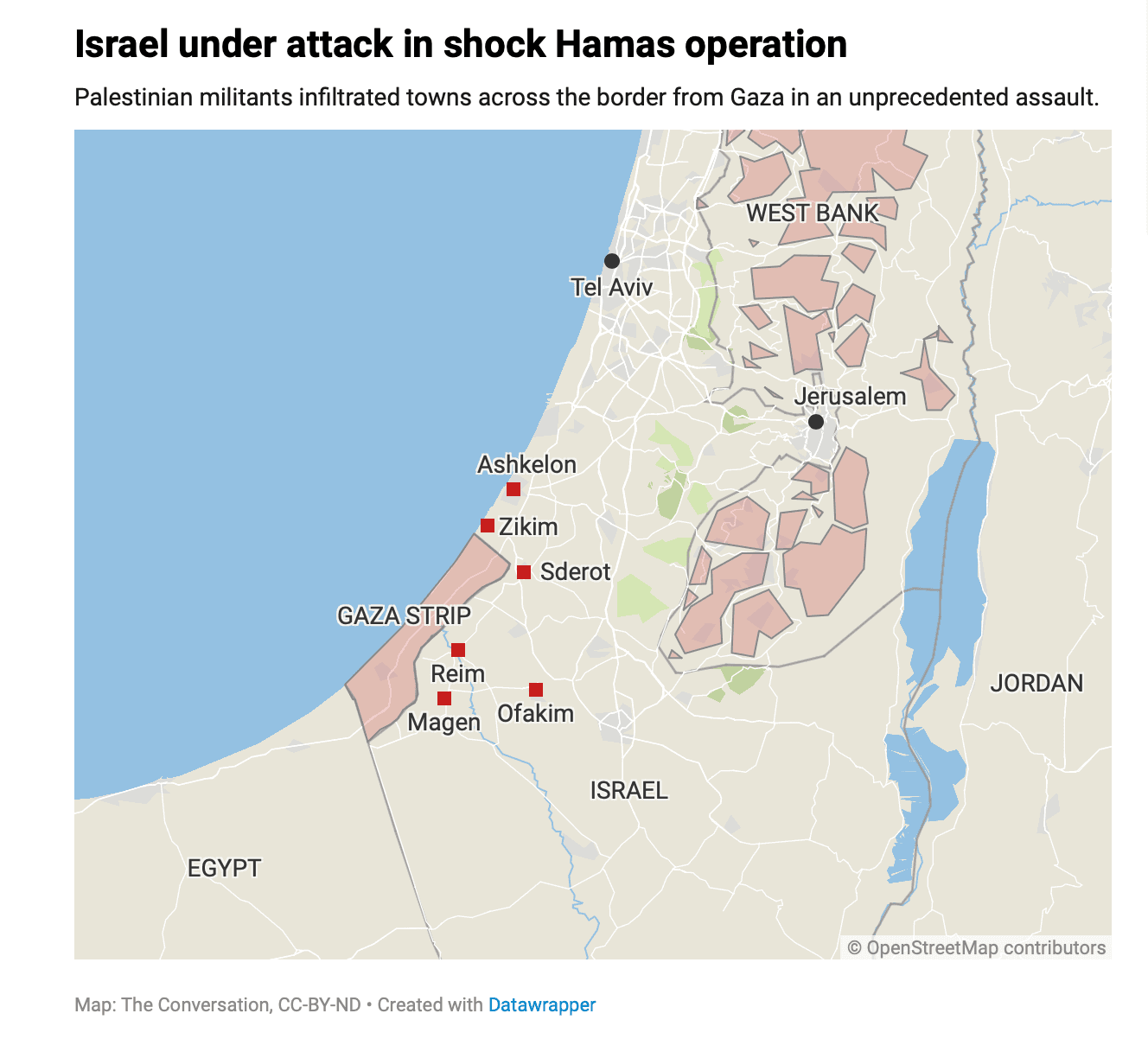

Early on Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas militants invaded southern Israel by land, sea and air, and fired thousands of rockets deep into the country. Within hours, hundreds of Israelis were killed, hostages taken and war declared. Fierce Israeli reprisals have already taken the lives of hundreds of Palestinians in Gaza, and many more will surely be dead by the time this war is over.

Because war it is. After the Hamas attacks began and the Israeli death toll grew, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared the country is at war, just as it was 50 years ago.

And that is not where the parallels end.

Both wars began with surprise attacks on Jewish holy days. In 1973, it was Yom Kippur, a day of atonement for Jews. This time it was Simchat Torah, when Jews celebrate reading the Torah.

Hamas, the Palestinian militant group in control of the densely populated Gaza Strip that adjoins Israel, seemingly hopes to send the same message that Egypt and Syria delivered in October 1973: They will not accept the status quo, and Israel’s military might will not keep Israelis safe.

The 1973 war proved to be a watershed moment not only in the Arab-Israeli conflict but also for the politics of Israel. Will this war be the same?

Caught flat-footed both times

Certainly, the sudden outbreak of war has again left Israelis deeply shocked, just as it did 50 years ago. This war, like the one in 1973, is already being framed as a colossal intelligence failure.

Although Israeli military intelligence had warned the government that the country’s enemies believed Israel vulnerable, the intelligence establishment did not expect Hamas to attack.

Rather, the intelligence assessment was that Hamas was most interested in governing the Gaza Strip and didn’t want to have a war with Israel, at least not for a while.

The assumption was that Hamas would be deterred from carrying out major attacks in Israel out of fear of Israel’s potential disproportionate retaliation bringing more devastation to Gaza. The enclave, home to 2 million Palestinians, many living in poverty, has still not recovered from the last major round of fighting in May 2021.

Instead, the intelligence establishment, and many analysts, believed that Hamas preferred to export Palestinian violence to the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where it could help to undermine the already weak and unpopular Palestinian Authority, led by Hamas’ political rival.

Their intelligence assessment has proved to be terribly wrong, just as it was prior to the outbreak of the 1973 war. Then, as now, Israel’s adversaries were not deterred by its military superiority.

Israeli intelligence not only misjudged the willingness of adversaries to go to war, but it also failed — both in 1973 and now — to recognize their enemy’s preparations.

This time, that failure is even more glaring given Israel’s extensive and sophisticated intelligence gathering capabilities. Hamas must have been carefully planning this attack for many months, right under Israel’s nose.

This is undoubtedly Israel’s worst intelligence failure since the 1973 war.

But it is not only an intelligence failure, it is also a military failure. The Israel Defense Forces, or IDF, was clearly not prepared for an attack of this magnitude — indeed, most IDF units were deployed in the West Bank.

It is true that IDF’s top brass had repeatedly warned Netanyahu that its military readiness had been diminished by the wave of Israeli reservists refusing to serve in protest of the government’s attempted judicial overhaul. Nonetheless, the IDF was confident that its defensive fortifications — especially the expensive hi-tech barrier that had been built around the Gaza Strip — would prevent Hamas militants from entering Israel, as they had previously done in a May 2021 raid.

But just as the so-called Bar-Lev defensive line along the Suez Canal failed to stop Egyptian soldiers from crossing the canal in 1973, the Gaza barrier did not stop Hamas militants. It was simply circumvented and bulldozed through.

The blame game begins

There will surely be the same blame game after this war as there was after the 1973 war. A commission of inquiry will probably be established, as happened after the 1973 war — the Agranat Commission — which published a scathing report, pointing the finger of blame firmly in the direction of Israel’s military and intelligence establishment.

But it is not Israel’s military and intelligence establishment that deserves most of the blame for this war. It is Israel’s political establishment — above all, Netanyahu, who has led the country since 2009, save for a one-year exception between 2021-2022.

The 1973 war was also due to a political failure, not only an intelligence failure. In fact, it was Israel’s political leadership, chiefly Prime Minister Golda Meir and her defense minister Moshe Dayan, that was primarily to blame because in the years before the war they had spurned diplomatic overtures from Egyptian President Anwar Sadat. The Israeli government was determined to retain parts of the Sinai peninsula — which Israel had captured in the 1967 war — even at the price of peace with Egypt.

Similarly, Netanyahu has ignored recent Egyptian efforts to broker a long-term truce between Israel, Hamas and fellow militant group Palestinian Islamic Jihad. And Israel’s current far-right government prefers to retain the occupied West Bank rather than pursue the possibility of peace with the Palestinians.

Moreover, the Netanyahu government has been preoccupied with its widely unpopular attempt to reduce the power and independence of Israel’s Supreme Court, a move seemingly aimed at removing a potential obstacle to a formal annexation of the West Bank. The domestic turmoil and deep divisions that the proposed judicial overhaul have created in Israel is almost certainly one reason why Hamas decided to attack now.

More broadly, with the latest attack it is clear that Netanyahu’s strategy to contain and deter Hamas has failed catastrophically. It has been catastrophic for Israelis, especially those living in the south of the country, and even more so for Palestinian civilians in Gaza.

Maintaining a blockade of Gaza for 16 years, crippling its economy and effectively imprisoning its 2 million residents, has not brought Hamas to its knees.

Rather, Hamas’ control over Gaza, sustained by repression, has only tightened. Innocent civilians on both sides of the border have paid a high price for this failure.

In the wake of the 1973 war, Meir was forced to resign, and a few years later, the ruling Labor Party — which had been in power, in various guises, since the country’s founding in 1948 — was defeated by Menachem Begin’s right-wing Likud Party in the 1977 general election. This was a watershed moment in Israeli domestic politics that was brought about in large part by the public’s loss of confidence in the then-dominant Labor Party as a result of the 1973 war.

Will history repeat itself this time around? Will this war finally spell the end for Netanyahu and Likud’s long dominance of Israeli politics? Most Israelis have already turned against Netanyahu, repelled by the mix of corruption scandals that surround him, his attempts to downgrade the power of the judiciary and the lurch to the right that his ruling coalition represents.

More Israelis may now do so because this devastating surprise attack surely contradicts any claim by Netanyahu of being Israel’s “Mr. Security.”

Whatever the outcome of this new war and its political repercussions in Israel, it is already clear that its outbreak will be long remembered by Israelis with great sadness and anger, just like the 1973 war still is.

Indeed, it will probably be even more traumatic for Israelis than that war was because while in 1973 it was members of the military bearing the brunt of the surprise assault, this time it is Israeli civilians who have been captured and killed, and on sovereign Israeli territory. In this crucial respect, then, this war is unlike the one in 1973.![]()

Dov Waxman is the Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Foundation professor of Israel studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news organization dedicated to sharing the knowledge of academic experts, under a Creative Commons license.

The story you just read is available for free because thousands of listeners and readers like you generously support our nonprofit newsroom. Every day, reporters and producers at The World are hard at work bringing you human-centered news from across the globe. But we can’t do it without you: We need your support to ensure we can continue this work for another year.

Make a gift today, and you’ll get us one step closer to our goal of raising $25,000 by June 14. We need your help now more than ever!