Narcs and spies: The drug war’s murky origins in Southeast Asia

Anti-narcotics agents call it deep cover: playing the role of a drug trafficker to mingle with actual criminals.

It’s acting, said former Drug Enforcement Administration agent Michael Levine — “Only, you’re acting with your audience about 2 inches from your face. And you’re going to die if your act is bad.”

It was the summer of 1971. President Richard Nixon had just declared the war on drugs. Levine — a Bronx-raised, federal agent in his early 30s — was gearing up for his toughest deep cover job yet. He’d invented a character for himself: “Mike,” an Italian mafioso from New York City.

“I’m not even Italian,” Levine said. “I’m a 100%, Middle Eastern Jew.”

But he was full of bravado and keen to infiltrate the Southeast Asian drug trade as Mike, a mafia capo eager to import heroin to the US.

At the time, the American media was fixated on Vietnam War veterans returning home addled by drugs — namely, powder-white Southeast Asian heroin produced in the Golden Triangle: a craggy, lawless expanse of Myanmar bordering Thailand, China and Laos.

Golden Triangle heroin refineries supplied kilos to South Vietnam where US troops could buy the drug in $2 vials.

American families feared their brothers and sons would bring home an addiction epidemic that spread across the US. Nixon understood this well: His war on drugs declaration mentioned “Vietnam” thrice.

For Levine, the new drug war was a chance to satisfy his own fix.

“I was addicted to adrenaline,” he said. “President Nixon, he called [drugs] our No. 1 enemy. So, it was an easy thing, if you’re an adrenaline junkie like me — like many of us — to cloak ourselves with that. Like, wow, this feels good. You’re making me into a hero.”

Nixon promised to assemble a new superagency to fight narcotics — what would later become the DEA — but this took time. In the interim, the drug war fell to a scattered array of state police, federal agents and US Customs. That’s where Levine worked: Customs’ Hard Narcotics division in New York City.

Levine concocted a plan. Fly to Bangkok, a regional hub for Southeast Asian heroin. Track down a few heroin traffickers. Go deep cover as Mike and earn their trust. He hoped to work his way up the supply chain, potentially exposing the whole distribution network.

Even before he reached Thailand, Levine had two specific heroin traffickers in his sights: Liang and Geh, both ethnically Chinese.

This duo, based in Bangkok, had recently sent a drug mule through JFK Airport with 3 kilos hidden in Samsonite suitcases — but not hidden well enough. Levine knew this because the drug mule, under interrogation in a back room at JFK, snitched on his suppliers.

Levine convinced him to write a letter, telling Liang and Geh that a mafia buddy (Mike) was en route to Bangkok with a business proposition.

Once in Bangkok, Levine tracked down the traffickers and turned on the charm.

“They were two skinny Chinese men, neatly dressed. And they loved me. I mean, they thought I was the tutti-frutti of the mafia.”

US intelligence files indicate that, in the early 1970s, Bangkok-based traffickers were struggling to set up a high-volume pipeline pumping heroin to the US.

Mike swooped in with the answer to their problems. No more sending piddly amounts of heroin via drug mules. Levine, as Mike, told Liang and Geh he could smuggle big shipments through New York’s ports.

Levine bonded with the traffickers, carousing through Bangkok’s neon-lit streets.

“They took me out to restaurants, to massage parlors,” Levine said.

They plied him with gifts: good liquor, fancy clothes.

“These two were obviously well-connected. We’d walk into a place and they were revered, with people backing away almost in fear.”

After about two weeks, Liang and Geh mentioned “the factory”: a refinery processing gooey, brown opium into pristine, white heroin.

“They said it could produce hundreds of kilos in a short time. This was it,” Levine said. “To me, the factory was my Mount Everest.”

The factory was located on the edges of the Golden Triangle: Thailand’s Chiang Mai province, which shares a mountainous border with Myanmar. Plans to visit the refinery took shape. The trip was nigh. Levine was staying in one of Bangkok’s snazzier hotels, the Siam Intercontinental, as befit a mafioso of Mike’s caliber. One night, at 2 or 3 in the morning, the phone rang. A caller summoned Levine to the US Embassy.

“They said, ‘Make sure you’re not followed.’”

So, Levine walked the streets for about an hour, making sure he wasn’t tailed, before slipping into the Embassy.

“That’s where I met my first CIA agent.”

The man was a bit older than Levine and “he’s dressed exactly like what you’d expect a CIA agent in a movie to look like.”

Khaki-colored outfit, lots of pockets.

“I remember the guy being pretty businesslike with me. He said, ‘You’re not going to Chiang Mai.’”

Levine was stunned. He’d flown halfway around the world on a crusade backed by the president. He couldn’t back down now.

“I told him, ‘They [Liang and Geh] are going to introduce me to the people running this shit. He says, “Well, we can’t protect you up there.’ I told him, ‘I didn’t take this job to be protected. I want to go.””

“Well, you’re not going,” the CIA officer said. “You don’t understand the big picture.”

Levine left the Embassy that dark morning with a head full of questions. Should he disobey the CIA officer and go to the factory anyway — or stand down? And what was the big picture?

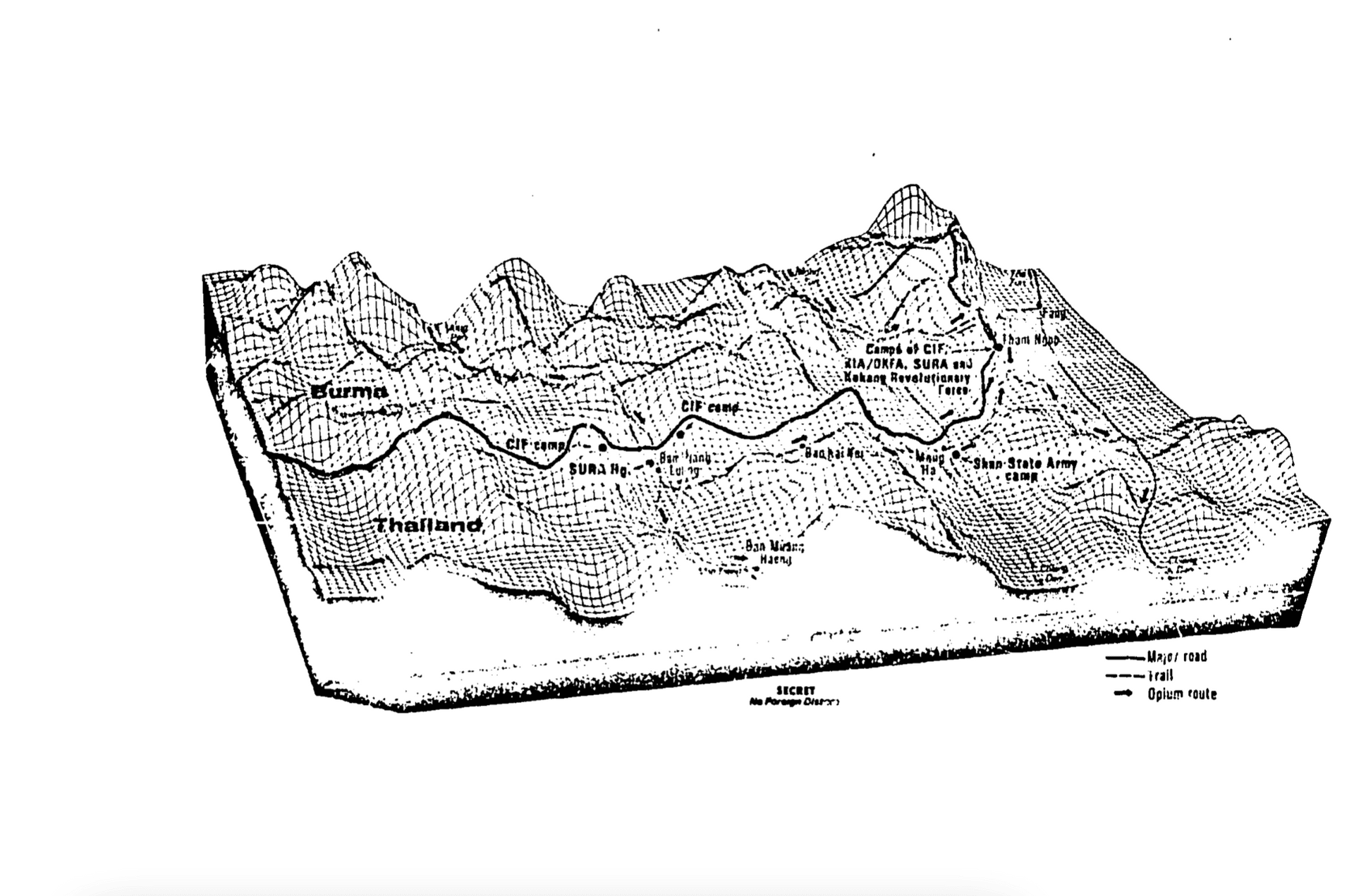

The CIA knew almost everything about the trafficking syndicate entrenched in Thailand’s mountains. Secret CIA files, since declassified, are strewn with minutiae about the syndicate: its secret routes, its military-grade weapons, locations of heroin labs. The CIA even calculated the average speed of the syndicate’s mules — actual, four-legged drug mules lugging sacks of opium from remote Myanmar villages down to borderland refineries.

But the CIA wasn’t hostile toward the syndicate, known inside the spy agency as the Chinese Irregular Forces or CIF. Quite the opposite: This trafficking organization was an intelligence-gathering asset for the CIA. The relationship stretched back to the early 1950s following Mao Zedong’s conquest of China. In China’s far western frontier, Yunnan province, thousands of Chinese people — many of them merchants and landowners — refused to accept Communist rule. Escaping into the jungles of neighboring Myanmar with their horses and mules, they had little chance of survival.

The CIA sent in unmarked planes to drop crates filled with guns and ammo, and urged the exiles to return to China and seize the country from Mao. The secret mission was a precursor to the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba 10 years later.

The Chinese exiles tried to take back their homeland but failed miserably. By the 1960s, the anti-communist exiles had all but abandoned hopes of “liberating” China. They instead focused on gathering up opium from Myanmar’s hills, one of the world’s lushest poppy-growing heartlands, and refining it into heroin inside hidden camps along the Thai border.

In short, they morphed into a drug syndicate armed with heavy American-made weapons: mortars, rifles and rocket-propelled grenades.

“Our guys had heavy weapons that no regular civilians could ever lay hands on,”said Jao Kai Wa, a former sergeant in the CIF.

By the summer of 1971 — when Levine showed up to Thailand — this syndicate dominated the Golden Triangle, accounting for “80% of the trafficking from Burma into Thailand,” according to CIA documents, “If the US hadn’t supported us,” Jao said, “we would’ve been screwed. We couldn’t have made it all work.”

The CIA supported the CIF with the help of its junior partner: Taiwan’s military intelligence division. They didn’t just provide exiled Chinese “irregulars” with weapons.

“We received radios, too,” Jao said. “That made everything very convenient.”

The CIA-Taiwan intelligence apparatus built radio towers at CIF bases and doled out long-range radio transmitters: clunky units with dials and antennae that strapped to traffickers’ backs.

Drug trafficking is a logistical exercise — moving stuff from points A to B — and the radios proved vital to running an efficient business. But that wasn’t the reason CIA officers bestowed radios on the syndicate. The spy agency used the CIF and other opium-smuggling armed groups in the Golden Triangle as sentries, surveilling the rugged mountains.

“They’d send these guys way out in the jungle to collect intelligence,” said David Lawitts, the official biographer of Bill Young, a legendary former CIA officer during the Cold War.

Young, raised in Burma, was adept at training Golden Triangle drug runners to work as spies.

“These groups knew who was moving through the mountains,” Lawitts said, “and what products were moving: weapons, ammunition, narcotics. And they knew who had the most power in these regions. Are the communists dominant? Are the host countries’ militaries dominant? They could provide all of that.”

In the 1960s and 1970s, communist guerrillas backed by North Vietnam were infiltrating parts of the Golden Triangle, namely Laos, and attempting to push all the way into Thailand, a US-backed, anti-communist stronghold.

The CIA was obsessed with halting their spread. The agency had long feared that Asian countries, absent US intervention, would be “plucked by the communists like ripe fruit.”

Though drug traffickers served as the CIA’s eyes and ears in the Southeast Asian hinterlands, these operations were kept secret from other wings of the US government — and for good reason. The spy agency knew, according to its own files, that Golden Triangle refineries were built with a specific purpose: serving the “increased demand for heroin by US forces in Vietnam.”

Any federal anti-narcotics agent seeking to expose the region’s heroin supply chain might end up, without knowing it, compromising a US intelligence asset.

“If a DEA agent is trying to run a sting on a particular heroin producer or trafficker, by definition, he’s not going to know if that guy is also allied with the CIA. Because all these operations are clandestine,” Lawitts said. “They’re not going to disclose them to anybody, not unless they have a need to know.”

That was the big picture.

But apparently, Levine — a brash, anti-narcotics agent, fresh off a plane from New York — did not have a need to know.

Back in Bangkok, in the summer of 1971, Levine had a choice to make. Flout the CIA’s orders and head to the factory, potentially blowing the lid off a trafficking syndicate targeting American shores, or stand down.

He stood down. Today, at the age of 83, Levine has no regrets. Asked what might’ve happened if he went to Chiang Mai, he said: “Dead. I don’t know how [I would] wind up dead, but dead. Tortured to death?”

No matter what, Levine said, “I wouldn’t have come back a hero.”

On July 1, 1973, Nixon finally established the Drug Enforcement Agency. Levine was among its first wave of agents, corralled from state and federal law enforcement bureaus and put under one central organization.

Their mission: Span the globe and thwart narcotics syndicates wherever they found them. Levine served the DEA for more than two decades; a fluent Spanish speaker, most of his deep cover work took place in South America.

But Levine said the war on drugs was — and is — fought with a caveat. At any time, CIA officers can shut down DEA investigations by citing “national security” concerns. Though this uncomfortable truth had long undermined White House propaganda — as first lady Nancy Reagan put it, there is “no moral middle ground” in the fight against drugs — disclosing the CIA’s protection of drug traffickers won’t change anything, Levine said.

“Americans will do nothing, absolutely nothing. The powers that be are very aware of that.”

By the CIA’s own admission, it backed drug-running, anti-communist rebels in Nicaragua in the 1980s. More recently, in Afghanistan, the agency supported anti-Taliban warlords who were known opium traffickers. The CIA’s collusion with Southeast Asian drug syndicates during the Cold War was among the first of many secret alliances, auguring more to come.

Our coverage reaches millions each week, but only a small fraction of listeners contribute to sustain our program. We still need 224 more people to donate $100 or $10/monthly to unlock our $67,000 match. Will you help us get there today?