Migrants stranded in Mexico rush to cross the US border before Title 42 ends

Many Venezuelan migrants congregate every day at the Plaza Misión de Guadalupe, in downtown Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, just across the border from El Paso, Texas.

“It’s a place to hang out and share stories, experiences and advice to cross the border into the United States,” said Manuel, a Venezuelan migrant who asked to use only his first name because he doesn’t have permission to live and work in Mexico.

Manuel, 24, has been stranded in Ciudad Juárez for a year on his way to the United States, where he hopes to find better opportunities to earn a living. He’s tried to seek asylum in the US, but was sent back to Mexico five times, under Title 42.

The pandemic-era policy that made it easier for the US to expel migrants, expires on Thursday at 11:59 p.m. Many asylum-seekers have decided to go ahead and present themselves to US authorities before that.

Some fear that stricter rules might prevent them from coming after the pandemic-era policy expires.

A lot of migrants were hoping that it would be easier to seek asylum after Title 42 ends, but US authorities have made it clear that there will be more restrictions.

US Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas on Wednesday said that the expiration of Title 42 doesn’t mean that the border will be open, and warned migrants about smugglers at the US-Mexico border ahead of the Thursday expiration date.

“Smugglers have long been hard at work spreading false information that the border will be open after May 11. It will not be. They are lying,” Mayorkas said at a press conference.

DHS is also rolling out a rule that assumes that anyone who doesn’t use a lawful pathway into the United States will not be eligible for asylum, and could face a five-year ban to enter the country, and even prosecution.

US authorities have been urging asylum-seekers to book an appointment through a cellphone app called CBP One. It was launched last year with the intention to process asylum-seekers in an orderly way and discourage them from rushing across the border.

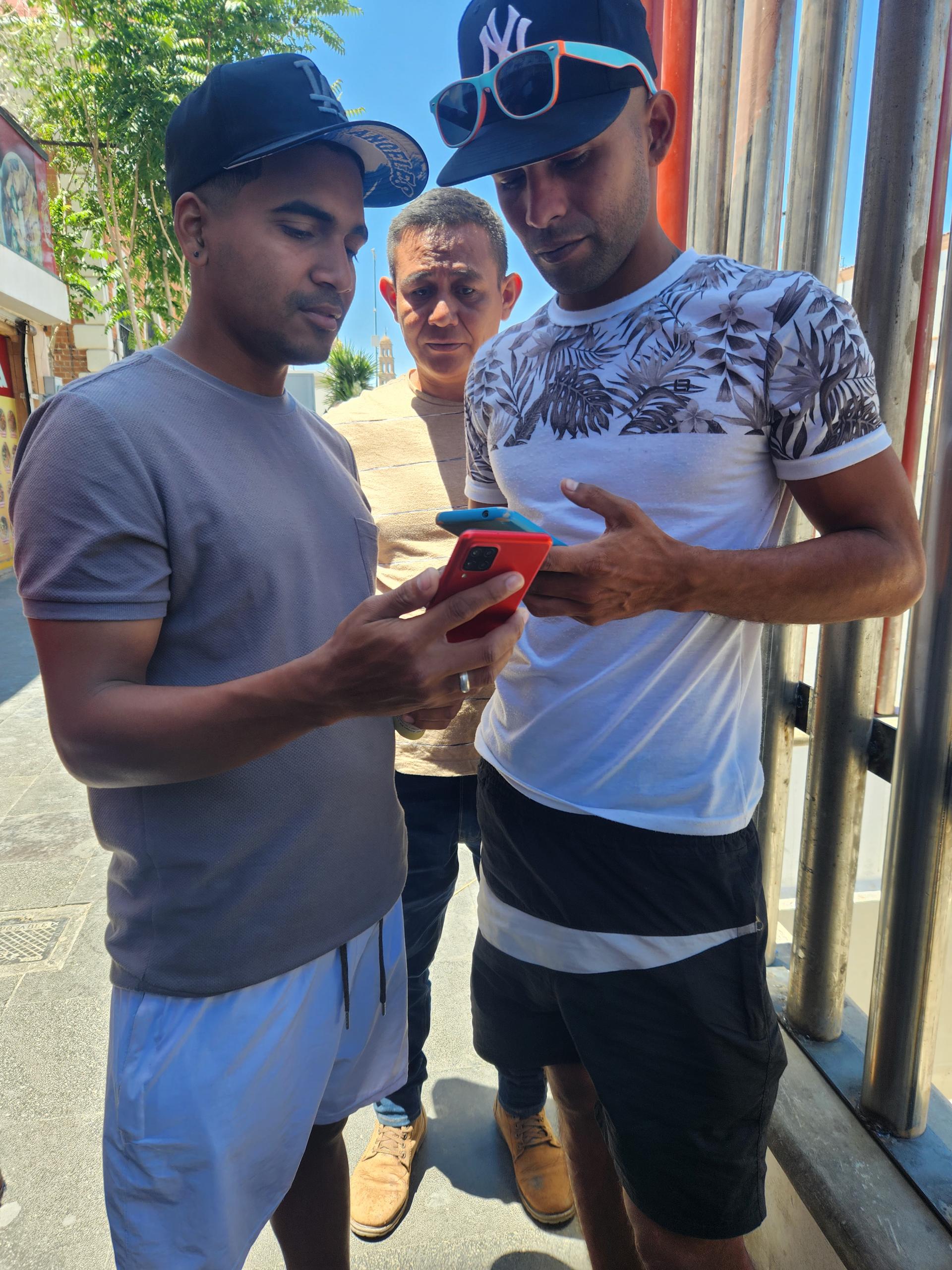

At the plaza in downtown Juárez, Manuel is trying to help other migrants in the plaza to get an appointment to seek asylum on the app.

The problem is that the app doesn’t offer enough appointments per day to keep up with the demand.

Manuel succeeded in getting an appointment for himself and his wife and two kids. He said it took 23 days, trying every single day. And the appointment is in a different port of entry, 800 miles away, so he’s figuring out how to get there.

But he’s lucky. A lot of people don’t get an appointment, because the required app often doesn’t work. Also, several shelters in Juárez and other bordering cities in Mexico said that they have found that the app is failing to register many people with dark skin tones.

All of these glitches are effectively barring people from their right to request entry into the US, said Stephanie Brewer, the Mexico director at the Washington Office on Latin America.

“If the door is shut to [migrants] seeking protection, they’re forced onto dangerous routes, to try across the border between ports of entry, and not go to these legal pathways,” she said.

Back on the plaza, the migrants keep trying their luck with the app.

“I haven’t been able to do it,” one said. “I filled in all the blanks and it shows an error.”

Carlos, another migrant from Venezuela, who also only gave a first name. He said that he’s been stranded in Juárez for two months.

“It’s hard to get permission to work in Mexico,” he said. “We mostly work under the table.”

But he said the worst part of living in Juárez is dealing with insecurity.

He said his wife and sister were robbed and abused by a group of men that got on a bus in Juárez, and that they live with constant fear of being extorted or kidnapped for ransom money.

Adam Isaacson is an expert on security in the Americas. He said that there are thousands of people who have spent many months in Mexican border cities.

“The larger number[s] are not as visible. Some of them are in a network of charity-run shelters [and] churches, and others pay to keep people, especially families, under these roofs for months. And there’s probably a larger number that has managed to get some resources together to rent a place somewhere in these border cities.”

Isaacson said they are all vulnerable.

“They probably have relatives in the United States, but in a place like Ciudad Juárez or Reynosa, they’ve got nothing.”