Victims of Guatemalan military seek justice for war crimes

On July 29, 1982, a paramilitary group known as the civil defense patrol, which took orders from Guatemala’s army, attacked the village of Rancho Bejuco — because the people there had refused to join the patrol and fight left-wing rebel groups. The patrol killed 25 people.

Pedrina Alvarado lost her mother and son in the massacre that occurred during one of the bloodiest periods of the nation’s civil war.

Last month, Alvarado traveled for four hours to hear the judge’s ruling in one of Guatemala’s most-infamous war crimes cases in Guatemala City.

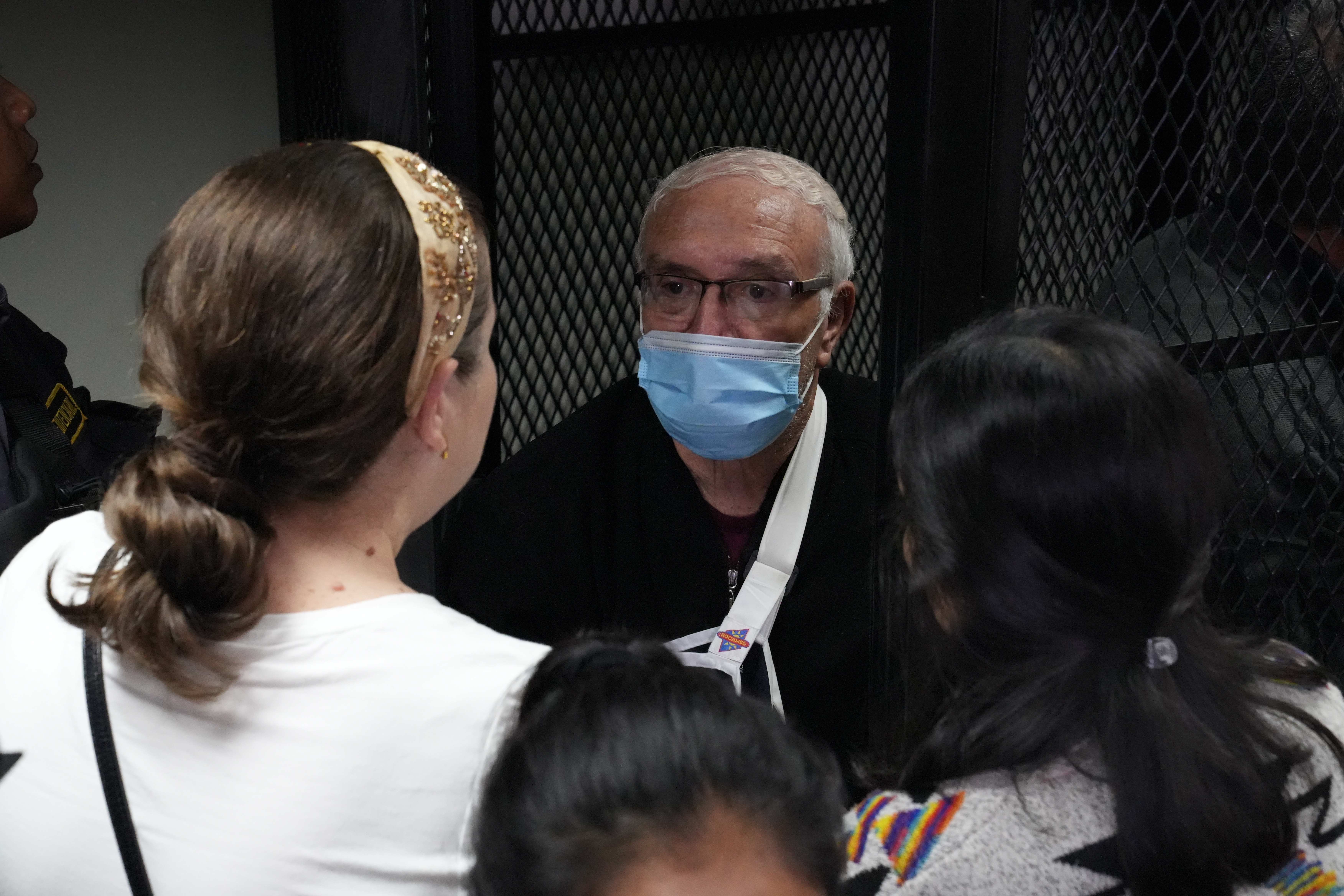

On Aug. 24, Judge Walter Mazariegos condemned the former colonel in charge of military operations around Rancho Bejuco to 20 years in prison for ordering attacks on Indigenous villages, which constituted crimes against humanity. But he let free eight members of the paramilitary group who carried out the massacre, arguing that they had no choice but to obey the military’s orders.

For Alvarado, who wore a traditional Mayan blouse known as the huipil and sat next to four other Indigenous women during the hearing, the verdict was not a true victory.

“I am leaving with a lot of sadness and frustration,” Alvarado said in tears after leaving the courtroom. “We worked so hard to have this case heard, we made so many sacrifices for this?”

More than 200,000 people were killed during Guatemala’s civil war that lasted from 1960 to 1996. According to the nation’s truth commission, at least 440 Indigenous villages were destroyed by the military as it tried to defeat rebel groups in rural areas.

Guatemalan officials have tried to investigate these war crimes since the country went back to civilian rule. And those efforts got a boost in 2007 when the UN set up an international commission against impunity in Guatemala (CICIG). But human rights groups say that lately, it’s been hard for victims to obtain justice, with courts stacked with judges who favor the interests of the nation’s elites, which includes some former military members.

Also, judges who have been tough on war criminals have received death threats, and some have been chased out of the country by prosecutors who act under the orders of an attorney general that has been sanctioned by the US for blocking corruption investigations.

“The military sectors and their allies never really went away,” said Jo-Marie Burt, a Guatemala expert at the Washington Office on Latin America. “Their power was just tempered a bit when this international sponsored body was in Guatemala.”

Burt is referring to CICIG, which was expelled from Guatemala a handful of years ago after it uncovered a corruption scheme that involved the nation’s president. Since then, Burt said, the Guatemalan justice system has become more partial to the interests of the nation’s elites.

“It’s not just trying to keep a few war criminals out of jail,” she said. “It’s a much broader project that is meant to restore the power control and impunity that this group of corrupt actors has over the entire political system.”

Some Guatemalans are hoping that this changes with the nation’s recently elected President Bernando Arévalo. He comes from the Semilla Movement, a small party, from outside of Guatemala’s power structure and has promised to fire officials who have been named in corruption investigations. He is also creating a special agency that will devise tougher anti-corruption laws.

Arévalo won the presidential election by a landslide in August as voters expressed their discontent with the nation’s establishment. But his rivals are now challenging the results in Guatemala’s courts, arguing that Arévalo’s movement was registered with fake signatures.

Analysts say that it will be tough for the new president to make changes to the nation’s judicial system if he makes it to his inauguration in January.

Arévalo will have to work with congress — where his party is a minority — to name new judges to Guatemala’s top courts. The constitution bars him from firing the nation’s controversial attorney general, so he will have to try to force her to resign.

“There is little the president can do to interfere in war crimes cases,” said Paulo Estrada, a human rights activist in Guatemala City who is also a plaintiff in another war crimes case.

He explained however, that the new president can change the leadership of the President’s Commission for Peace and Human Rights, which is the agency in charge of complying with international human rights rulings.

In the past, the agency has been notorious for ignoring orders from international courts that say the government should provide reparations to victims and help them to find their disappeared relatives.

One ruling that has been ignored, for example, orders the Guatemalan government to build a memorial for 183 activists and political leaders who were abducted and disappeared by Guatemala’s military in the early 1980s and are now part of what’s known as the Military Diary cases.

“We would hope that this new government complies with those international court orders,” said Estrada, whose father and uncle are among the disappeared.

In the meantime, war crimes cases continue to advance slowly in Guatemala’s local courts.

The families involved in the Rancho Bejuco trial have already said they will appeal the judge’s decision to let most of those who perpetrated the massacre go free. They believe that the ruling violates international law.

“You can’t absolve people because they were obeying orders,” said Lucia Xiloj, the victims’ lawyer. “Perhaps, you can give them a smaller sentence, but obeying orders should not be an excuse for impunity.”

We want to hear your feedback so we can keep improving our website, theworld.org. Please fill out this quick survey and let us know your thoughts (your answers will be anonymous). Thanks for your time!